Surprise! Monster Burst of Radio Waves Arose in Tiny Galaxy

For the first time, scientists have directly traced an incredibly intense, blindingly bright burst of radio waves — known as an FRB — back to its home galaxy. Surprisingly, this impressive cosmic radio flasher has somewhat humble origins, according to three new studies detailing the findings.

FRB stands for "fast radio burst." These flickers of light were just discovered in 2007, and although they last for just a fraction of a second, they release more energy than our entire sun will radiate in 10,000 years. Eighteen FRBs have been detected, but scientists estimate that one of these bursts occurs somewhere in the sky about once every 10 seconds.

What cosmic event could release such an intense burst of radio waves? That's still a mystery, but narrowing down the precise location of one of these radio blasts is a big step toward cracking the case. [8 Baffling Astronomy Mysteries]

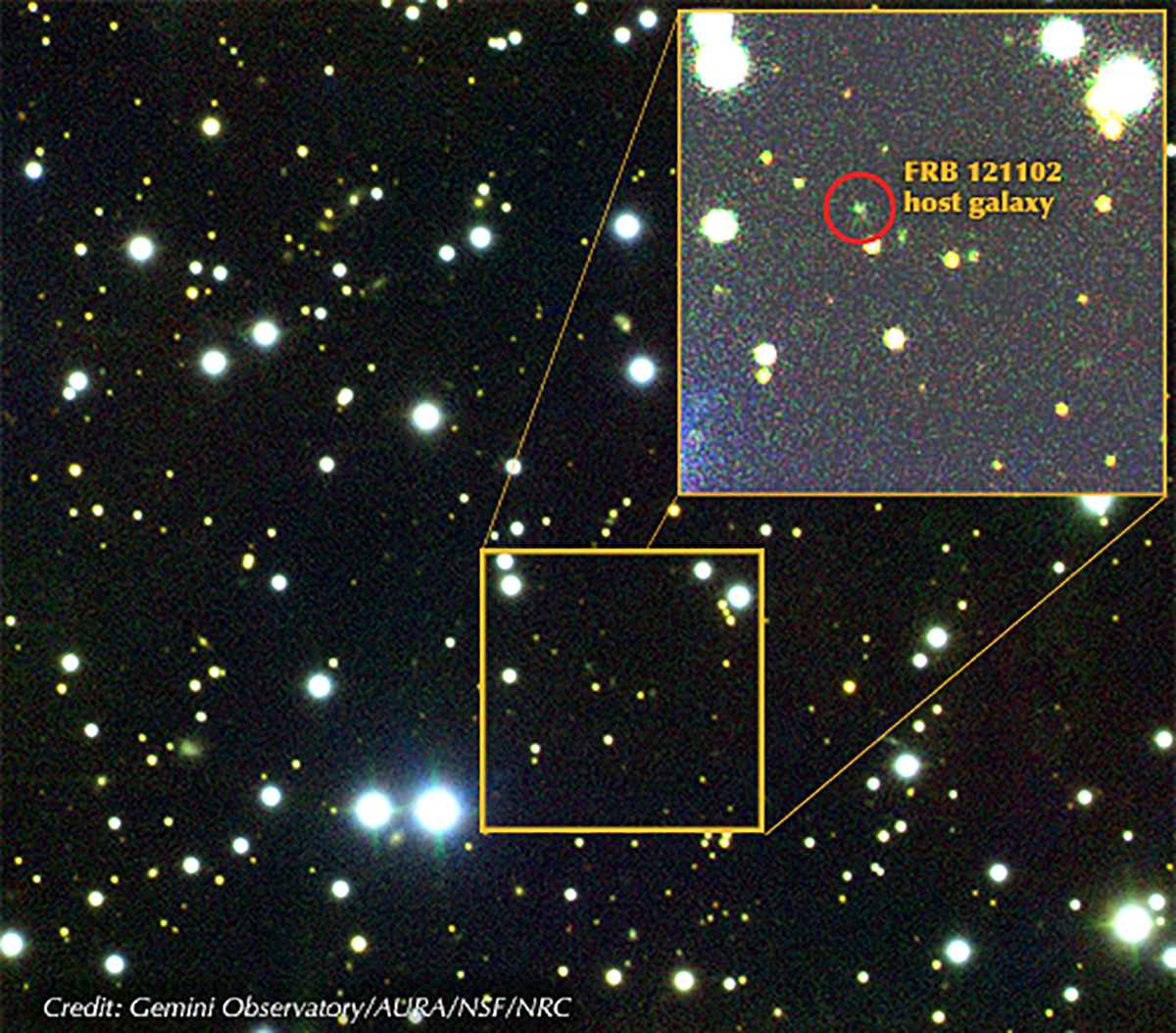

The new study shows that the burst, known as FRB 121102, originated about 3 billion light-years away from Earth, from inside a dwarf galaxy — a collection of stars much smaller than large galaxies like the Milky Way.

A surprising source

The fact that FRB 121102 originated from a dwarf galaxy was a bit unexpected, said Cees Bassa, an astronomer at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) and a co-author of one of the three new studies.

"We were not sure what to expect, but I think the whole team was surprised to see that our exotic source is hosted by a very puny and faint galaxy," Bassa said in a statement from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany (where some of the co-authors are based).

The surprising finding could provide clues about the source of these radio bursts.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One would generally expect most FRBs to come from large galaxies which have the largest numbers of stars and neutron stars," study co-author Shriharsh Tendulkar said in a statement from McGill University in Montreal, where he is a postdoctoral researcher. "This dwarf galaxy has fewer stars but is forming stars at a high rate, which may suggest that FRBs are linked to young neutron stars." (Neutron stars are dense objects that form when a star explodes and its remaining material collapses on itself.)

Difficult subjects

Because FRBs appear and then disappear in the night sky very quickly, they are incredibly difficult to detect and study. A telescope must already be looking at the region of the sky where the flash appears in order to see it, and there's no time to alert other telescopes and have them turn their eyes toward the source. That makes it extremely difficult to refine the location and distance of these flashes. (A study released earlier this year claimed to have traced an FRB back to its source galaxy, but doubt was later thrown on that finding. In addition, that study used an indirect method to trace the FRB's origin, whereas the studies of FRB 121102 trace its location directly.)

But FRB 121102 is unique because it's a repeater. This radio burst was first discovered in November 2012 by astronomers using the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, and was seen by that telescope again in 2014. In 2016, it was caught flashing nine times, during a dedicated study using the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico. Additional observations of the burst were also taken with telescopes belonging to the European VLBI Network, including the 100-meter (330 feet) Effelsberg radio telescope in Germany.

Those observations helped researchers narrow down the source of this radio flasher. With the 8-meter (26 feet) Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, the researchers then showed that the FRB was coming from a dwarf galaxy located about 3 billion light-years away.

"Before we knew the distance to any FRBs, several proposed explanations for their origins said they could be coming from within or near our own Milky Way galaxy," Tendulkar said in a statement from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. "We now have ruled out those explanations, at least for this FRB."

The repeated appearance of FRB 121102 could also offer clues to its origin: If the flashes are caused by a neutron star, they might be expected to occur regularly. Spinning neutron stars that radiate beams of light are known as pulsars, and they appear to flicker on and off because of a lighthouse effect: The beam sweeps across Earth as the pulsar spins, moving in and out of view with a regular frequency. Astronomers are now studying FRB 121102 with radio, optical, X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes to search for clues.

Tendulkar said two other classes of extreme events are also known to occur frequently in dwarf galaxies: long-duration gamma-ray bursts, or very bright flashes of high-energy light, and superluminous supernovas, or very bright exploding stars.

"This discovery may hint at links between FRBs and those two kinds of events,” Tendulkar said.

But some of the authors also cautioned that the repeating nature of FRB 121102 could indicate that it is somehow physically different than other known FRB's. FRB 121102 is not alone. The researchers also found a persistent source of radio waves in the same area of the sky, and the evidence suggests that both sources of radio waves are connected somehow; they either arose from the same source or are linked in some other way, the researchers said.

The results of these studies will appear in three separate papers on Jan. 5 — one in the journal Nature and two in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter