Tightly Packed Alien System's Planets Align Every Month

If you want to see a planet align with another in our solar system, you usually have to wait a while. Even the speediest planet, Mercury, takes 88 days to make a circuit around the sun.

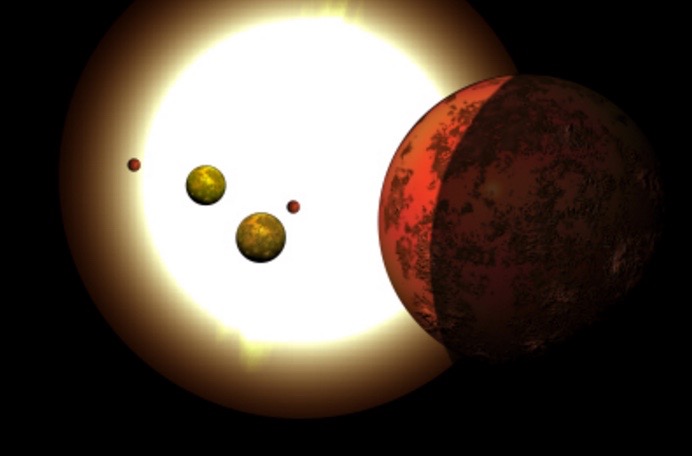

But in many alien systems discovered by NASA's Kepler space telescope, planets are huddled close to their host stars and zoom around it in just a few days. And in one system, Kepler-80, the planets are "synchronized" in such a way that they repeat an alignment every 27 days, returning to the same positions relative to each other, a new study finds.

Kepler-80, a system about 1,100 light-years away, has five known planets. These worlds orbit their star in periods of 1.0, 3.1, 4.6, 7.1 and 9.5 days. Packed tightly around their star, the four outermost planets return to the same position relative to each other in less than a month, according to the new study. Such a condition is called resonance, and it is one reason the system can stay stable. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

The study team — led by Mariah MacDonald, who was an undergraduate at Florida Institute of Technology at the time — analyzed Kepler data of the Kepler-80 system. They determined that the four outer planets are all between four and seven times the mass of Earth. The researchers think these worlds are rocky "super-Earths," though two likely have atmospheres composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. (Earth's air is primarily nitrogen and oxygen.)

Kepler-80-type configurations actually aren't all that uncommon; they are called Systems with Tightly- spaced Inner Planets, or STIPs, and hundreds of them have been found to date. What's unusual about Kepler-80 is the system's orbital resonance, which allows the planets to repeat their positions so often. It's also rare to have a good idea of the composition of four exoplanets in a single system, researchers said.

The new study has been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal. You can read a copy of it at the online preprint site Arxiv.org here: http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.07540.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.