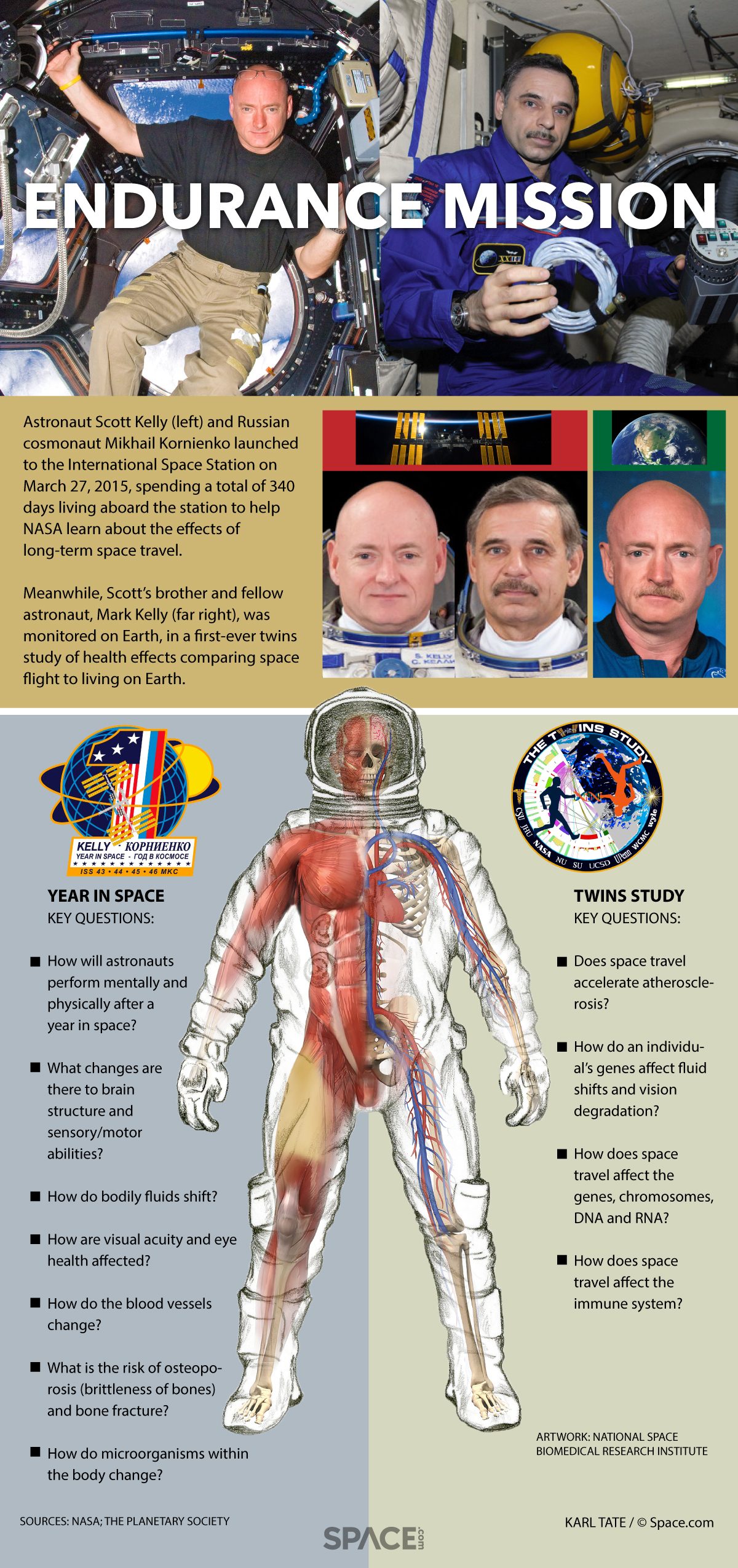

Astronaut Scott Kelly Is Home from a 1-Year Mission, But the Science Continues

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly is back on Earth after a 340-day stay in space, but the "one-year mission" is far from over.

The goal of sending Kelly and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko to the International Space Station for nearly a year was to learn about the ways that long-duration spaceflight affects the human body and psyche. The two space travelers returned home to Earth on March 1, but the science experiments that will study the two men are still in progress.

The information collected before, during and after this extended stay in space will soon be in the hands of scientists, who will analyze it to better understand how humans might fare on a long trip to Mars or some other destination. Today (March 4), scientists involved with the One-Year Mission answered questions about the mission during a news conference on NASA TV, as well as via a Reddit "Ask Me Anything" (AMA) earlier in the day. [Welcome Home! Year-in-Space Astronaut Scott Kelly's Earth Return in Photos]

The typical stay on the space station lasts only six months, and while Kelly and Kornienko are not the first people to spend a year in space, the international One-Year Mission is the most in-depth study of how a mission this long affects the human body.

"From the perspective of NASA's Human Research program, [the One-Year] Mission is not yet over just because the flight has landed," John Charles, associate manager for international science for NASA's Human Research Program, wrote during the Reddit AMA.

In today's news conference, Charles told reporters that the studies conducted on Kelly and Kornienko have not been completed and that no conclusions can be made yet. Many of the studies require studying Kelly prior to, during and after flight, which means tests and sample collection will continue now that he is on the ground. Some of the experiments will not have their final data sets until September.

In addition, some of the blood and urine samples Kelly collected during flight are coming back to Earth on a SpaceX vehicle in May. That means scientists will still be working on their results well into 2017, and perhaps beyond.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The data analysis is only now beginning in earnest," Charles said in the news conference.

Scientists also conducted tests on Kelly's twin brother, retired astronaut Mark Kelly, to see how spaceflight affects humans on a genetic level.

"Especially for the Twins Study, the metabolic data that were acquired are going to be batch analyzed, which means that all the samples or most of the samples will be analyzed by the same technician, with the same hardware, at the same time and the same place," Charles said in the news conference. "So any differences we'd see are not related to variations between the technician or the location or the time or how long they were in the freezer and so forth."

Scott M. Smith, nutritional biochemistry laboratory manager for NASA's Human Research Program, wrote in the AMA that scientists anticipated publishing a "main paper" about the Twins Study "with likely smaller piece papers to follow."

Back on the ground

As soon as Scott Kelly exited the Soyuz space capsule on March 1 when it landed in Kazakhstan, he underwent tests to see how well an astronaut might be able to perform physical tasks on the surface of Mars immediately after completing a long spaceflight.

"What I've been told is that he completed all the testing, which, in itself, is a real accomplishment because it's a lot of work to do after a very strenuous — and, I think, harrowing — episode when you land in the Soyuz," Charles said. "So he has continued to perform at very significant levels. He's been there for all the studies; he's been a full participant and seems to be doing it by taking it in stride."

So, if Kelly's year in space had been a trip to Mars, would he have been able to land on the Red Planet, get into a spacesuit and immediately begin work?

"I get the sense that he could have," Charles said. "That's my strictly qualitative, nonprofessional assessment having never interacted with the spacesuits myself. But if he couldn't, I can't imagine somebody that could have."

During the NASA news conference, a reporter asked Charles what his top three concerns are for long-duration spaceflight, and how the One-Year Mission addresses those concerns.

At first, Charles' response sounded organized. He mentioned concerns about the psychological impacts of a trip to Mars, where astronauts are confined to a small space with the same group of people. He also noted that a ship traveling to Mars might have long radio delays with Earth, making it impossible to talk to friends and family in real time.

But the answer quickly spiraled away from a short list of three items. Charles said the people in NASA's human spaceflight division are concerned about the changes in astronaut circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles, the need for medical care on a trip to Mars (when astronauts can't even talk to a doctor on the phone in real time because of the radio delay), radiation exposure once astronauts leave the protective shield of Earth's magnetic field, the challenge of providing nutritious food that is also satisfying to the astronauts so they don't lose interest in eating, changes to astronauts' vision, changes in bone integrity and bone loss and changes in muscle function. And NASA is concerned about how those problems will affect the astronauts not just while they're traveling to Mars, but also once they return to Earth.

"Essentially, every kind of body system that you can imagine is influenced by the factors of spaceflight," Charles said. "You name it — we're interested in all of it."

"Missions like this help us to answer the questions that we have in front of us," Charles continued. "So, at the end of the space station era or thereafter, we can give a 'go' to the manager of the Mars program and say that yes, we think we understand what needs to be done to keep astronauts happy, healthy and performing at [a] high level — not just alive, but performing at a high level for the duration of the Mars missions."

Another yearlong mission?

While the tests on Scott Kelly and Kornienko will be extremely useful, Julie Robinson, chief scientist for the International Space Station Program, said there is still a need for more test subjects in order to fully understand how long-duration spaceflight affects the human body.

"We really would like to see 10 or 12 crewmembers with long-duration data [prior to a human Mars mission] in order to be confident … that we know what all the risks are and alleviated them all," she said. "So, at its core, scientifically, we need more subjects."

Charles confirmed in the Reddit AMA that "NASA's Human Research Program has requested additional year-long missions on ISS, but all the other aspects of such missions must be considered by all the partner agencies, so no final decision has been made one way or the other."

"One thing that's really important is getting this first set of data back," Roberts said, referring to the data on Kelly and Kornienko. That information may suggest to NASA scientists that they should either try to send up more long-duration crews right away, or wait until later in the life of the space station.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter