Traces of the First Stars in the Universe Possibly Found

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

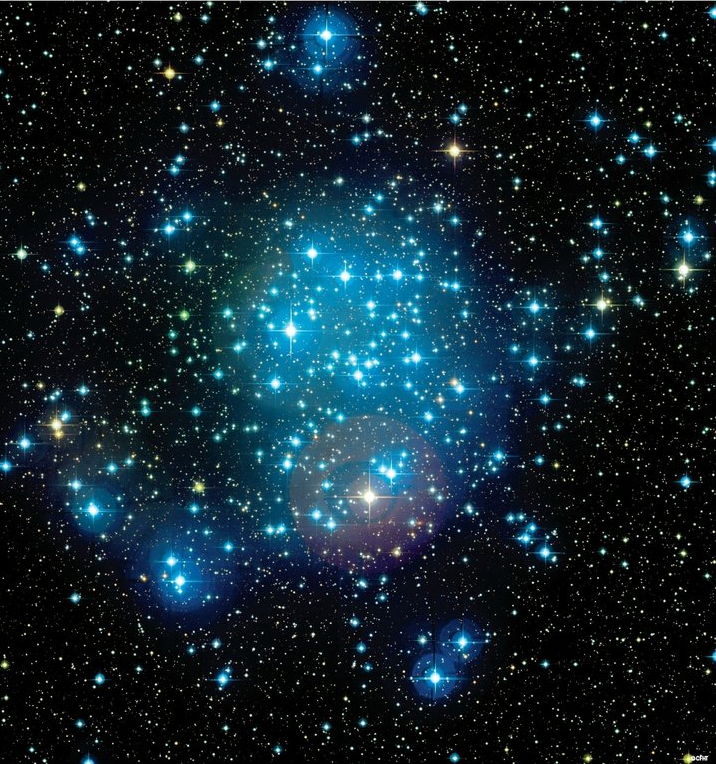

An enormous cloud of dust and gas may bear the fingerprints of the first stars in the universe.

The distant cloud contains only a tiny amount of relatively heavy elements, which are manufactured in the hearts of stars, suggesting that these traces may have come from some of the first stars that ever existed.

"The reason why we care [about the first stars] is intricately related with the air we're breathing right now," study co-author John O'Meara, of Saint Michael's College in Vermont, said last week at a press conference at the 227th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Kissimmee, Florida. "Early on in the universe, we didn't have those heavy elements [such as oxygen] at all." [From the Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

Traces of the past

The universe's first stars were built primarily out of hydrogen and helium, the dominant elements that existed shortly after the Big Bang.

Fusion transformed the material at these stars' hearts into heavier elements, which were then blasted into space when the stars died in violent supernova explosions. Subsequent generations of stars incorporated this material into their bodies, building even heavier elements in their cores.

"It's clear the history of the universe is very much the history of the increase in the relative amounts of heavy elements over time," said O'Meara, who worked with study lead author Neil Crighton, as well as Michael Murphy, both of whom are based at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia.

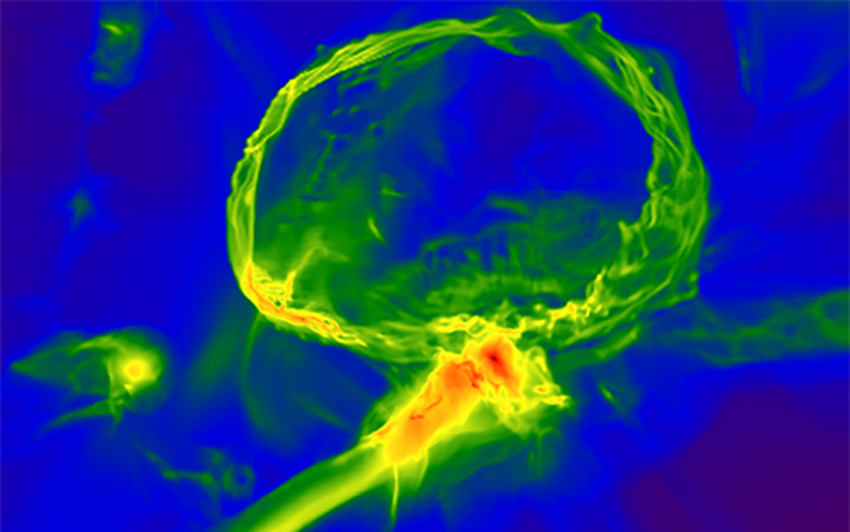

The study team used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile to study an ancient gas cloud as it appeared only 1.8 billion years after the Big Bang, which created the universe about 13.8 billion years ago.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As light from an extremely bright background object known as a quasar streamed through the cloud, the astronomers were able to determine the composition of its constituent gas. They found that the ancient cloud contained an extremely small percentage of heavy elements — traces that may have been scattered by the first generation of stars.

Previous surveys have revealed clouds of hydrogen and helium gas, but they were pristine, untouched by the heavy elements built within stars. This ancient gas cloud contains the smallest measurable traces of heavy elements ever found, the researchers said.

"It is the lowest amount of heavy elements ever determined in a gas cloud like this," O'Meara said.

'Down in the weeds'

The problem with studying massive clouds of gas in the early universe isn't that they are rare; it's that they are extremely common. The light from a single quasar can pierce through multiple clouds as it streams toward Earth. According to O'Meara, this can "muddle" the process of distinguishing heavy elements, because the signals are overlapping.

"It was our willingness to go down in the weeds, to try to find those very rare systems where you could make that measurement" that made the observations possible, he said.

Other such heavy-element-tinged clouds may exist as well, but scientists need to pore over a number of observations to find alignments where the signals can be precisely measured.

"It's not to say they're not out there in abundance," O'Meara said. "The problem is just getting lucky."

As instruments like NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) come online in the near future, the hunt for such gas clouds might become easier. Rather than being limited to quasars, which are relatively few in number, scientists should be able to use galaxies as their background light source.

"Once you can start using galaxies as a background source, you go from hundreds of thousands of objects on the sky to tens of millions," O'Meara said.

Searching the universe for signs of these clouds today will help narrow down the list of potential targets for JWST in the future, he added.

"We're building James Webb in part to find these things," O'Meara said. "It would be nice to get at least a teaser trailer of what we might find with Webb."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky