Life on Earth Can Thank Its Lucky Stars for Jupiter and Saturn

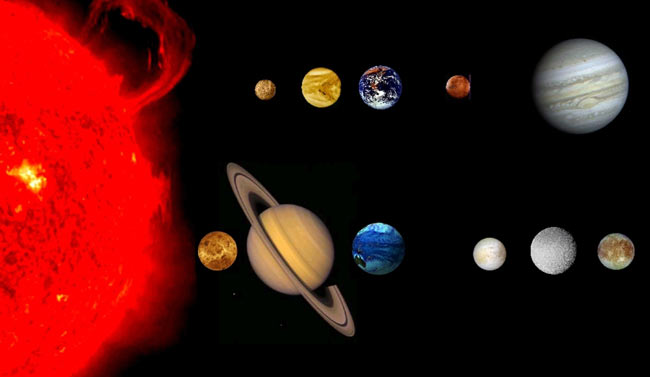

KISSIMMEE, Fla. — Without Jupiter and Saturn orbiting out past Earth, life may not have been able to gain a foothold on our planet, new simulations suggest.

The two gas giants likely helped stabilize the solar system, protecting Earth and the other interior, rocky planets from frequent run-ins with big, fast-moving objects, researchers said.

In other words, giant planets appear to have a giant impact on giant impacts. [Moon Made by Giant Impact with Earth: New Evidence (Video)]

"If you don't have giant planets in your system, you have a very, very different planetary system," Tom Barclay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California said here Friday (Jan. 8) at the 227th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Barclay and his colleagues found that massive impacts — such as the one involving the proto-Earth that's thought to be responsible for the formation of the moon 4.5 billion years ago — would happen more frequently, and for a longer time periods, in solar systems that lack giant outer planets.

Such giant impacts could result in the loss of a planet's atmosphere, potentially making the world uninhabitable, Barclay said.

"If you have giant planets, your last giant impact happens somewhere between 10 and 100 million years [after planet formation], which is pretty fine — it's like what happened on Earth," Barclay said. "If you don't have giant planets, the last giant impact can happen hundreds [of millions] to billions of years in. This really is a risk to habitability."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

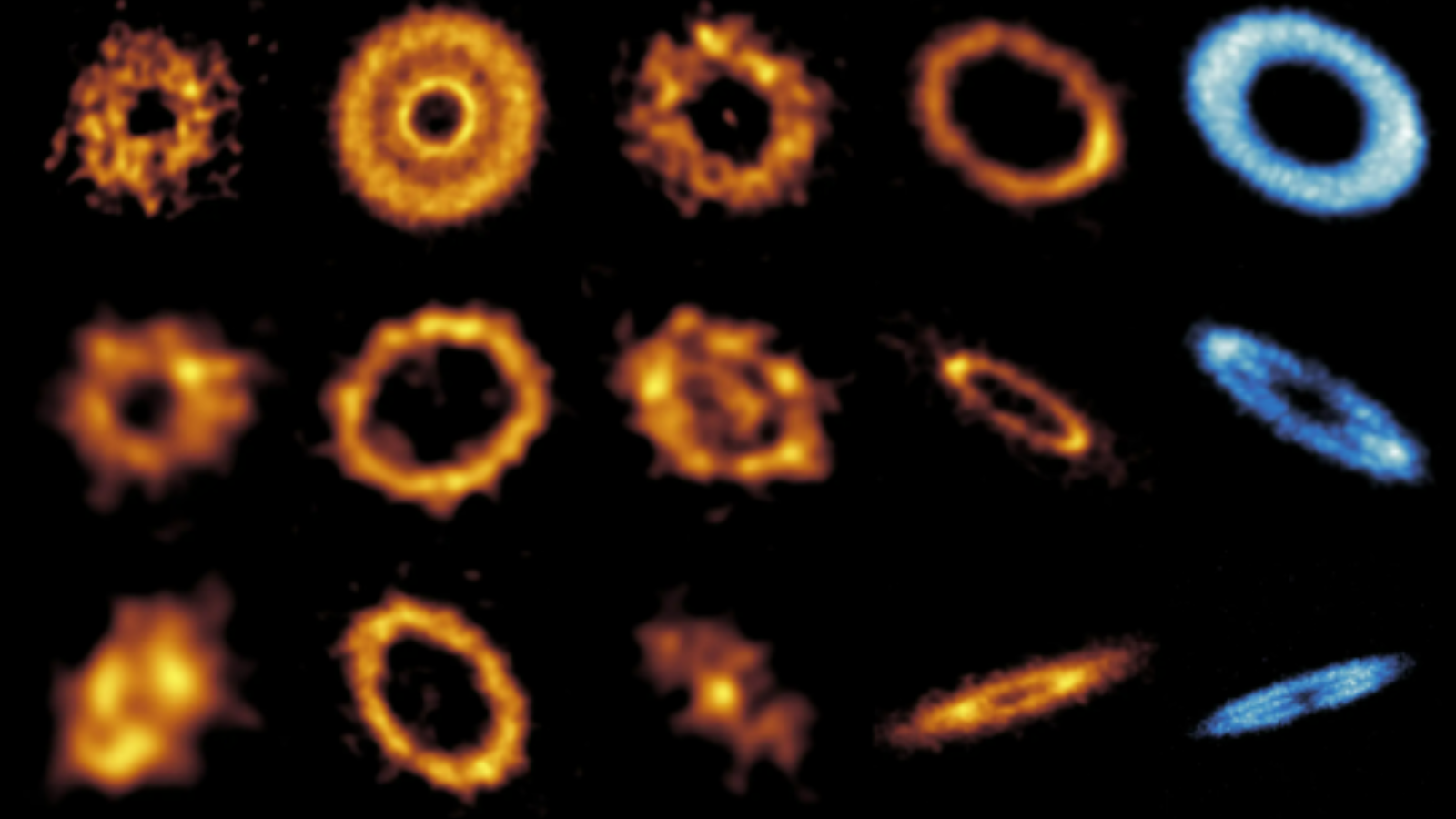

As a solar system forms, planetary building blocks and debris zoom around in a broad disk before eventually aggregating into planets with stable orbits. Barclay's group started its simulation after Mars-size planet embryos had already formed in the system, and looked at cases with and without giant planets on the outer perimeter.

The researchers found that, with giant planets around, the remaining small solar system bodies were either ejected out of the system more quickly — because of the angular momentum the gas giants add to the system, Barclay said — or became a part of the existing planets sooner.

Without the influence of giant planets, the fragments formed a large, dangerous cloud orbiting close within the system that took much longer to disperse — kind of like a closer-in version of the icy Oort Cloud, a shell of debris that orbits in the outer solar system and occasionally casts comets toward Earth.

The giant planets' effect was only a small part of what the researchers were investigating with their new simulation, which attempts to fix two major problems with other models of the final stages of planet formation, Barclay said. First, the researchers took into account the fragmenting that occurs when objects ram into one another, rather than assuming they combine perfectly. And second, they ran hundreds of simulations to see all the possible ways the chaotic formation process could play out.

"Things that aren't rare but aren't especially common don't show up in typical simulation runs like this," Barclar said. "So you need to run a really large number."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.