Future of Space Exploration Could See Humans on Mars, Alien Planets

The future of manned space exporation is bright, according to some space experts.

Humans may one day tread across some of the alien worlds that today can be studied only at a distance. Closer to home, private industries like Mars One seek to establish a permanent settlement on the Red Planet. At the Smithsonian Magazine's "The Future is Here Festival" in Washington, D.C. this month, former astronaut Mae Jemison and NASA engineer Adam Steltzner spoke optimistically about the future of manned space exploration.

"Exploration and the curiosity that motivate it are fundamentally human," Steltzner said during the conference. [Gallery: Visions of Interstellar Starship Travel]

Steltzner served as the lead engineer for NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. He helped to design and test the rover's one-of-a-kind descent system, but he isn't solely focused on robotic exploration of the solar system.

"I look forward to human footprints on the surface of Mars in my lifetime," he said.

Landing a human on the Red Planet would be far trickier than landing a robot. For instance, Curiosity hit the Martian atmosphere at 15 times the acceleration of gravity (15 gs). Traveling at such extreme speeds would be disastrous for humans, who only experience 1g while standing on Earth's surface. At 15gs, the retinas would detach from human eyes, Steltzner said.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn't try.

"Humans should be involved in exploration," Steltzner told the audience.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That form of exploration could come in a number of ways. In addition to kicking up dust on a moon or planet in the solar system, Steltzner suggested another way to spread humans throughout the galaxy.

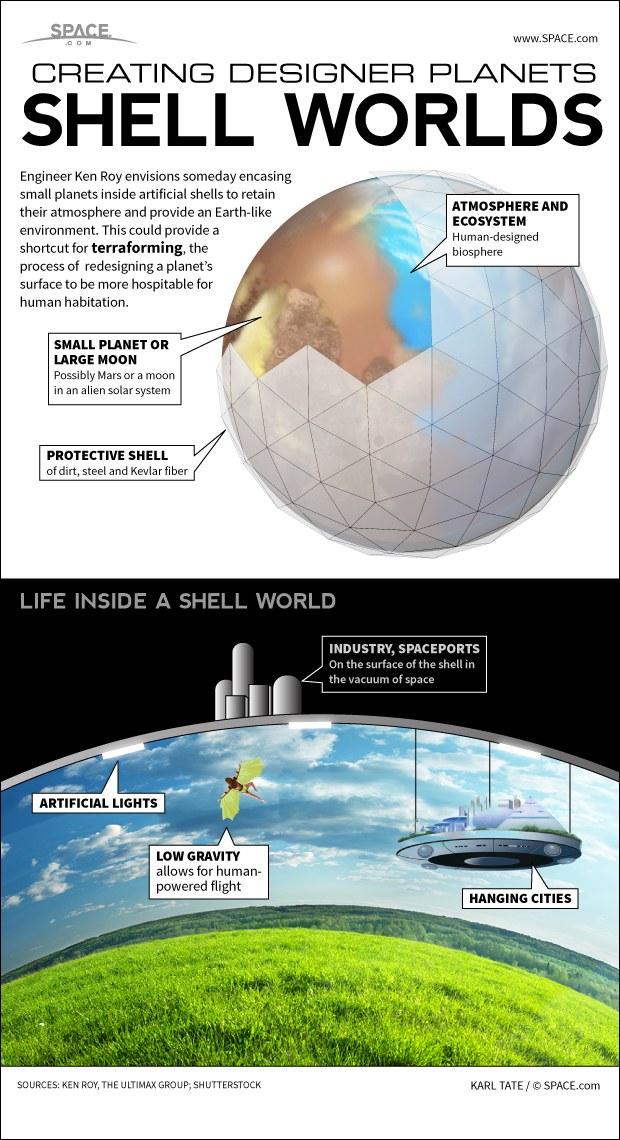

"Imagine hurtling durable terraforming bacteria to another world, conceivably with the idea of shaping that body," Steltzner said.

Although the idea that bacteria — and life — could hitch a ride on traveling rocks to spread life to other planets is not new, Steltzner suggested a deliberate program that sounds more like science fiction than science fact. Such bacteria could carry our genome and the instructions to reassemble it after landing on a planet (and, one assumes, after the planet has been terraformed to support such life).

Steltzner described the process as "printing human beings organically over time."

Whether or not such a program would be accepted by humans as "succeeding" at space exploration and colonization is another question entirely. Steltzner noted that humans define themselves as more than their genes, and that our experiences and connections also shape us. But in terms of spreading humanity through the galaxy, such seeding might be the easiest and most effective.

In addition to curiosity-motivated exploration, Steltzner pointed out that as long as humans remain on a single planet, we are at risk of extinction when disaster strikes.

"Our real estate portfolio suffers from a concentration of risk," he said.

Such disasters could come from the outside, such as impacts like those that destroyed the dinosaurs or, eventually, the death of the sun (though we have more than 4 billion years to wait for that).

They could also come from within, Steltzner said. A growing population, climate and environmental issues, and keeping our biosphere in check are all problems that humans impact as well as struggle with. [How Interstellar Space Travel Could Work (Infographic)]

This leads to what Steltzner termed the "terraforming paradox," in which the skills and abilities necessary to change another planet to suit human needs are the same that are necessary to keep Earth suitable and sustainable.

"We won't be able to get that job done [on other planets] until we figure out how to get it done here," he said.

Although long-term terraforming projects may be out, visiting planets in the solar system remains a not-to-distant possibility, and one not hindered by the level of technology.

"Technology didn't slow us down getting to the moon," Steltzner said. "Technology won't slow us down getting to Mars."

'An inclusive journey'

Mars may be one of the closest planets humans want to colonize, but it certainly isn't the only one. Mae Jemison described the 100-Year Starship project to an interested audience.

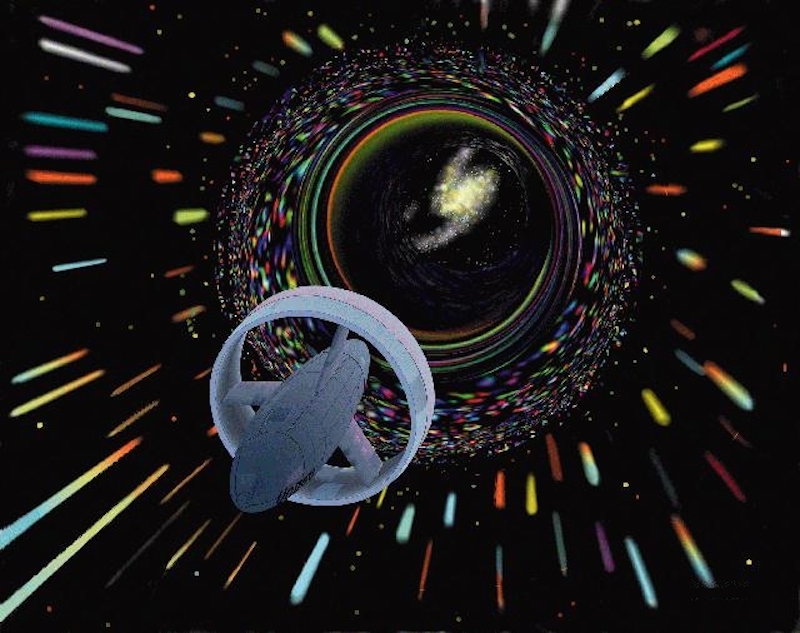

Funded by NASA's Ames Research Center and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the 100-Year Starship project aims to develop the tools and technology necessary to build and fly a spaceship to another planetary system within the next 100 years. The program isn't necessarily concerned with building the ship itself as much as it seeks to foster innovation and enthusiasm for interstellar travel.

"The reason we're not on the moon has nothing to do with technology and everything to do with public will and commitment," Jemison said.

As a result, the project, which Jemison heads, seeks to increase public enthusiasm for space as well. The 100-Year Starship program not only includes engineers and astrophysicists, but also artists and science fiction writers.

"It has to be an inclusive journey," she said.

Though many people object to funding the space program when there are humanitarian needs that have to be met on Earth, Jemison points out that such exploration often leads to innovation and unexpected technology that make an impact on Earth-based programs.

"I believe that pursuing an extraordinary tomorrow will create a better world today," she said.

Traveling to another star takes far more time than just developing the necessary technology. Jemison compares the distance to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star, to that between New York City and Los Angeles. If NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft, which launched in 1977, was en route, it would have traveled only 1 mile in the past four decades.

At that rate, it would take 70,000 years to reach Proxima Centauri.

Without the development of a method to warp or shrink space-time, or a new propulsion system—both ideas that the 100-Year Starship program is exploring—humanity would need to find a way to overcome some of its instability problems.

To get there, Jemison emphasized that everyone must be involved in the process.

"The public did not leave space," she said while discussing the reduced enthusiasm. "The public was left out of space."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky