Earth-Size 'Lava Planet' With 8.5-Hour Year Among Fastest Ever Seen

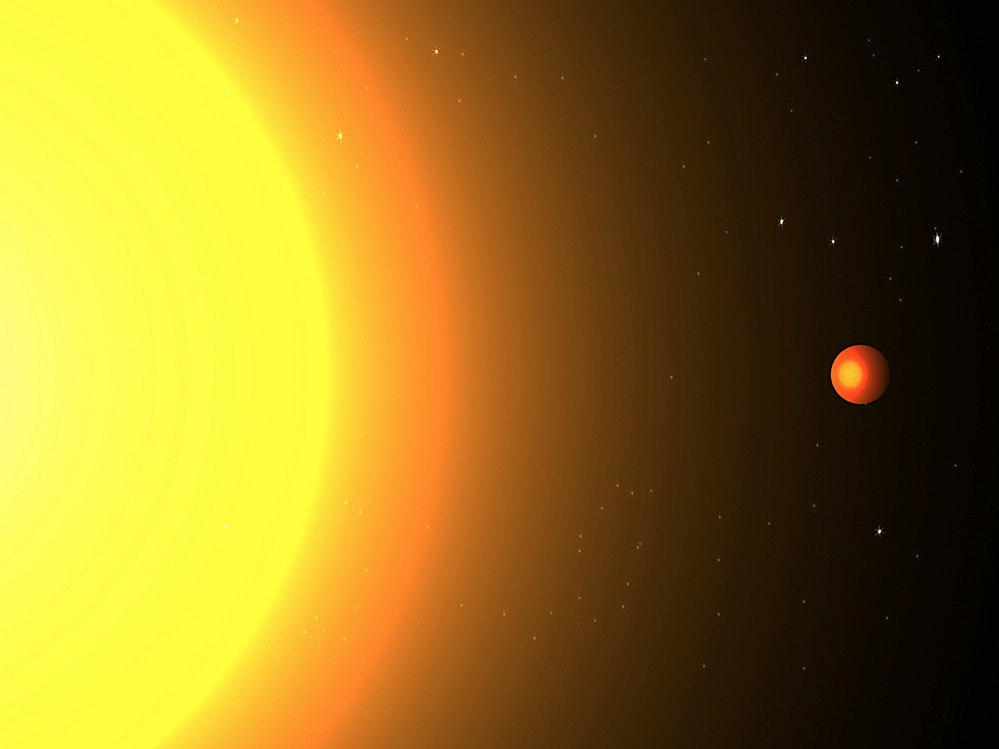

Astronomers have discovered a hot Earth-size planet so close to its star that a year on that exoplanet lasts just 8.5 hours, making it one of the fastest alien planets ever seen.

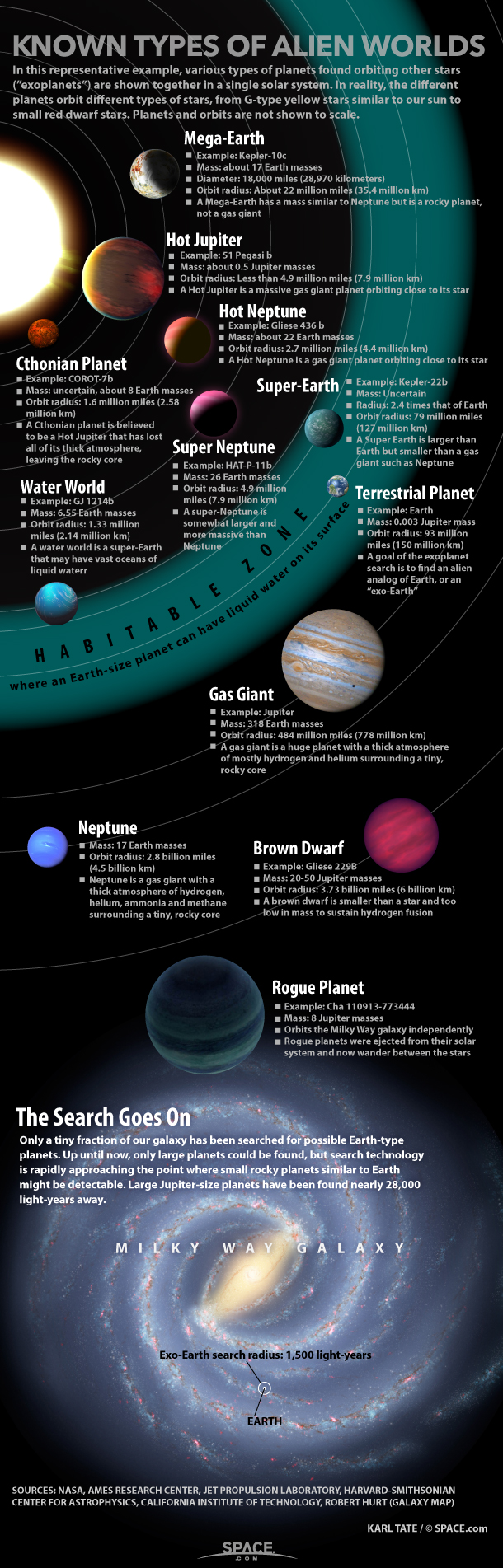

The small orbital period — one of the shortest ever discovered for an alien planet among the worlds discovered by NASA's Kepler Space Telescope — means the planet is far outside what is considered the habitable zone of its star, where liquid water, and maybe life, could exist. In fact, scientists have described the new world as a so-called "lava planet."

The find, however, excites astronomers because the host star of the planet, called Kepler-78b, is bright enough for other telescopes to spot the world. This is a relieving note for the research team given that the Kepler Space Telescope's prime exoplanet mission officially ceased Thursday (Aug. 15), scientists said. The spacecraft had to cut its prime planet-hunting mission short when two of its orientation-controlling reaction wheels failed. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

"With a lot of effort and a lot of patience, you could detect the transit from the largest telescopes," Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda, a Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who led the research, told SPACE.com. "We also think it's possible with the Hubble Space Telescope. From space, you should not have any issue [spotting it.]"

A hot Earth

Kepler-78b is about 100 times closer to its star than the Earth is to the sun, and orbiting in a star system that is about 750 million years old — about six times younger than the solar system. The planet's surface bakes at an iron-melting temperature somewhere between 3,680 degrees Fahrenheit (2,026 degrees Celsius) and 5,120 degrees Fahrenheit (2,826 degrees Celsius).

Among other planetary candidates found by Kepler, only a handful have periods less than half a day long. The shortest confirmed orbital period is 10.9 hours, which belongs to Kepler-42c, while the shortest unconfirmed one (held by a planet candidate called KOI 1843) is only 4.3 hours.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sanchis-Ojeda's team noted that many researchers are looking at longer-period planets that could be in habitable zones, which excites scientists because of the possibility of life existing on these worlds. But the researchers decided to plumb Kepler's data to focus on tight orbital periods, to see if more of these planets exist and how many of them are out there.

"Hot Jupiters," or Jupiter-size planets that are close to their stars, are the most common finds in this field because they are easy to detect. Spotting something the size of Earth, therefore, was a special moment for the team.

"It turned out to be a really rewarding session because we ended up finding this planet," Sanchis-Ojeda said.

Next steps

Because Kepler-78b transited, or crossed in front of, the face of its star, which is similar in size to Earth's sun, the team was able to pinpoint its size at a little larger than one Earth radius.

And in a more unusual find, the scientists discovered the planet's surface is so hot that it shines brightly in visible light, allowing the team to isolate the light of the planet from its star.

As Kepler-78b passed behind its star, light curve measurements allowed researchers to confirm that the planet is reflecting at least some of the light it receives from its star. How much light is unknown, and will require further observations to determine, Sanchis-Ojeda noted.

Follow-up observations could also determine the mass of the planet, which would give a sense of its composition. The team is almost certain that Kepler-78b is rocky, because most planets of that size are rocky, as opposed to gaseous.

The findings were published Friday (Aug. 16) in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.