New Satellite Lets Anyone Experiment in Space

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

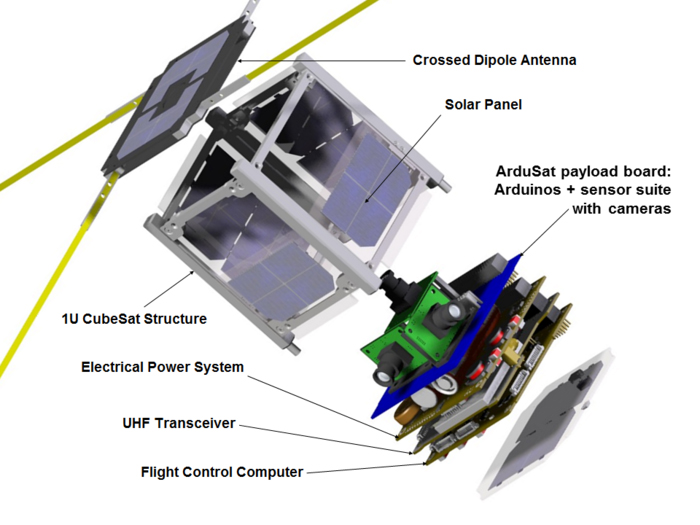

For a few hundred dollars, anyone can now buy time to run their own experiments aboard a small satellite set to launch next year. A physicist and two engineers are building a 4-inch (10 centimeters) cubic satellite designed to carry hobbyist processors into space and run citizen-written programs.

The researchers, including consultants to NASA's Ames Research Center, want to develop a cheap spacecraft that makes space science affordable to everyday people, according to their Kickstarter page. They're now gathering donations for spaceworthy hardware, assembly and launch.

If funded, the ArduSat spacecraft will carry more than 25 sensors, including cameras, a Geiger counter, a device that measures magnetic fields and the world's first open-source spectrometer, called Spectrino. The ArduSat team has already wired the sensors together and they work as expected, according to their project page. Donors that buy experimentation time can use any of those sensors. The pricing for ArduSat time starts at $325 for three days.

To participate, would-be space scientists submit computer code that works on a hobbyists' processor called Arduino (the namesake of the ArduSat). Participants can write their own code, send something they've found on the Internet, or use the ArduSat team's library of template codes.

Team members, led by NASA consultant and physicist Peter Platzer, will first test the computer programs in an identical ArduSat sitting in a lab on Earth. Once they've debugged all the code, they'll upload it into space. The team has already written the software to send participants' experiments into space, they said. Participants get their data back, online, when their experimentation time is over.

For those who aren't interested in paying to run an experiment, donors can also donate $150 to take at least 15 pictures from space. Photo-takers get to steer the satellite for their photos, which ArduSat will send to their email inboxes. Those who donate $300 get to broadcast a message from space for one day as ArduSat flies over every point on Earth. (So far, one person has purchased one broadcast.)

To ensure all this hobbyists' equipment will work in the high radiation and extreme temperatures of space, the ArduSat team plans to surround the cheap stuff with spaceworthy materials. The computers actually running the satellite and exchanging data with Earth, for example, are manufactured for spaceflight. The entire satellite's contents fit inside a cubic frame made by a company specializing in small satellites.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As soon as Platzer and his colleagues raise enough funds, they will start assembling the ArduSat. They plan to finish testing the system before February 2013. They'll then secure permission for the ArduSat to hitch a ride with an International Space Station supply mission within the next 12 months. If they don't get permission to launch with a governmental program, they've secured funding to launch with a private company.

If they exceed their funding goal of $35,000 by July 15, they'll attach a second 4-inch cube onto the first, allowing for more experiments and more sophisticated sensors.

The team expects the little cube —or cubes —to stay in orbit for between six months and two years. At the end of its lifetime, it will lose altitude and burn up in the Earth's atmosphere.

Innovation News Network is a former contributing news agency for Space.com. Formed in 2020, INN has become a vital online and in-print source for the latest news revolving around research, emerging science, technology, policy and innovation topics around the world. They provide daily news updates and focus on sourcing articles and features from a variety of policymakers, scientists, researchers and organizations covering arenas of discovery and innovation.