Huge Moon Crater's Water Ice Supply Revealed

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A crater on the moon that is a prime target for human exploration may be tantalizingly rich in ice, though researchers warn it could just as well hold none at all.

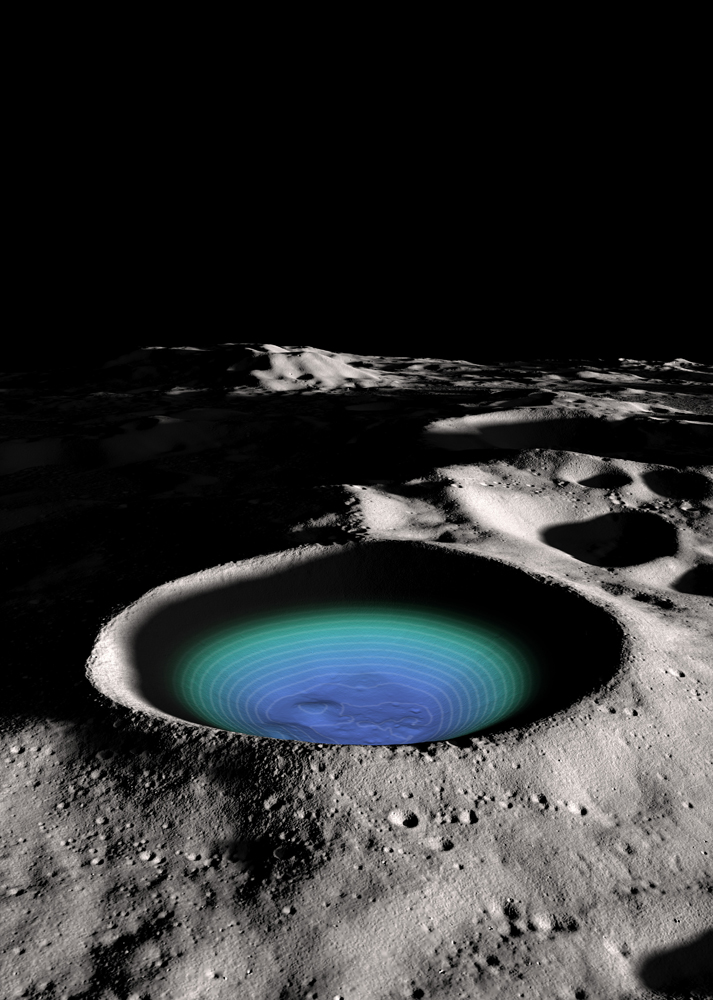

The scientists investigated Shackleton Crater, which sits almost directly on the moon's south pole. The crater, named after the Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, is more than 12 miles wide (19 kilometers) and 2 miles deep (3 km) — about as deep as Earth's oceans.

The interiors of polar craters on the moon are in nearly perpetual darkness, making them cold traps that researchers have long suspected might be home to vast amounts of frozen water and thus key candidates for human exploration. However, previous orbital and Earth-based observations of lunar craters have yielded conflicting interpretations over whether ice is there.

For instance, the Japanese spacecraft Kaguya saw no discernible signs of ice within Shackleton Crater, but NASA's LCROSS probe analyzed Cabeus Crater near the moon's south pole and found it measured as much as 5 percent water by mass. [Photos: Searching for Water on the Moon]

Now scientists who have mapped Shackleton Crater with unprecedented detail have found evidence of ice inside the crater.

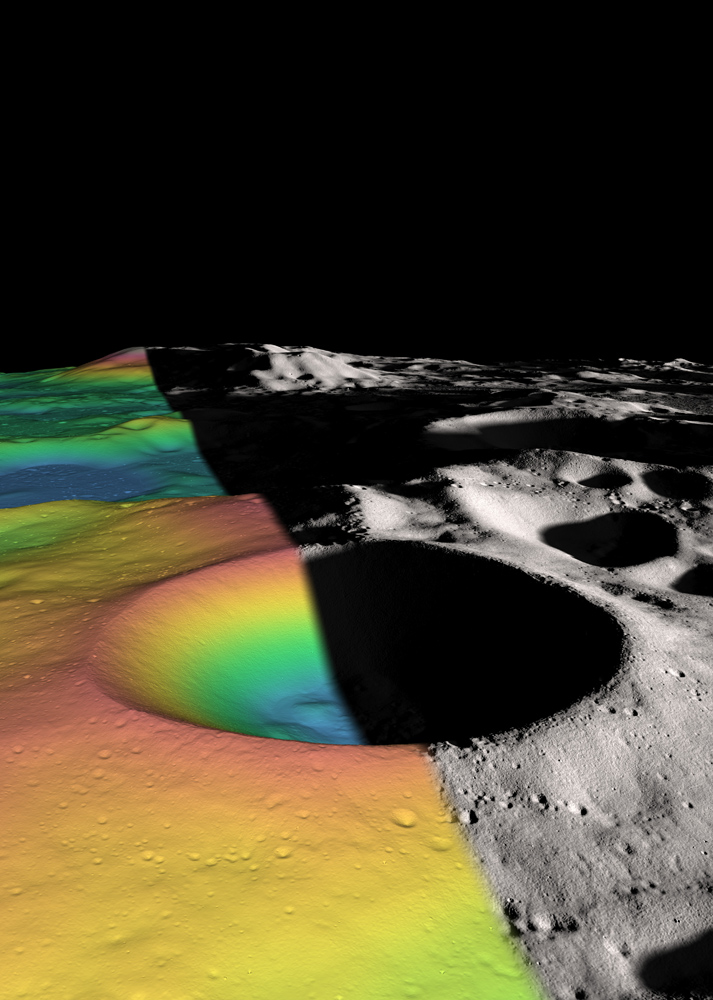

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter essentially illuminated the crater's interior with infrared laser light, measuring how reflective it was. The crater's floor is more reflective than that of other nearby craters, suggesting it had ice.

"Water ice in amounts of up to 20 percent is a viable possibility," study lead author Maria Zuber, a geophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told SPACE.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Don't get your hopes up, though. The amount of ice in Shackleton Crater "can also be much less, conceivably as little as zero," Zuber cautioned.

This uncertainty is due in part to what the researchers saw in the rest of the crater. Bizarrely, while the crater's floor was relatively bright, Zuber and her colleagues observed that its walls were even more reflective.

Scientists had thought that if highly reflective ice were anywhere in a crater, it would be on the floor, which live in nearly permanent darkness. In comparison, the walls of Shackleton Crater occasionally see daylight, which should evaporate any ice that accumulates.

The researchers think the reflectance of the crater's walls is due not to ice, but to quakes. Every once in a while, the moon experiences shaking brought on by meteor collisions or the pull of the Earth. These "moonquakes" may have caused Shackleton's walls to slough off older, darker soil, revealing newer, brighter soil underneath.

Whether or not the crater floor is brightly reflective due to ice or other factors is also open to question.

"The reflectance could be indicative of something else in addition to or other than water ice," Zuber said. For instance, the crater floor might be reflective because it could have had relatively little exposure to solar and cosmic radiation that would have darkened it.

Zuber noted that the measurements only look at a micron-thick portion of Shackleton Crater's uppermost layer. "A bigger question is how much water might be buried at depth," Zuber said, adding that NASA's GRAIL mission will investigate that possibility.

The researchers also used the orbiter to map the crater's floor and the slope of its walls. This topographic map will help shed light on crater formation and study other uncharted areas of the moon.

"We would like to study other lunar polar craters in comparable detail," Zuber said. "There is much to be learned here."

The scientists detailed their findings in the June 21 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us