2 'super-Earth' exoplanets spotted in habitable zone of nearby star

NASA's TESS spacecraft found the two planets, which are slightly larger than Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

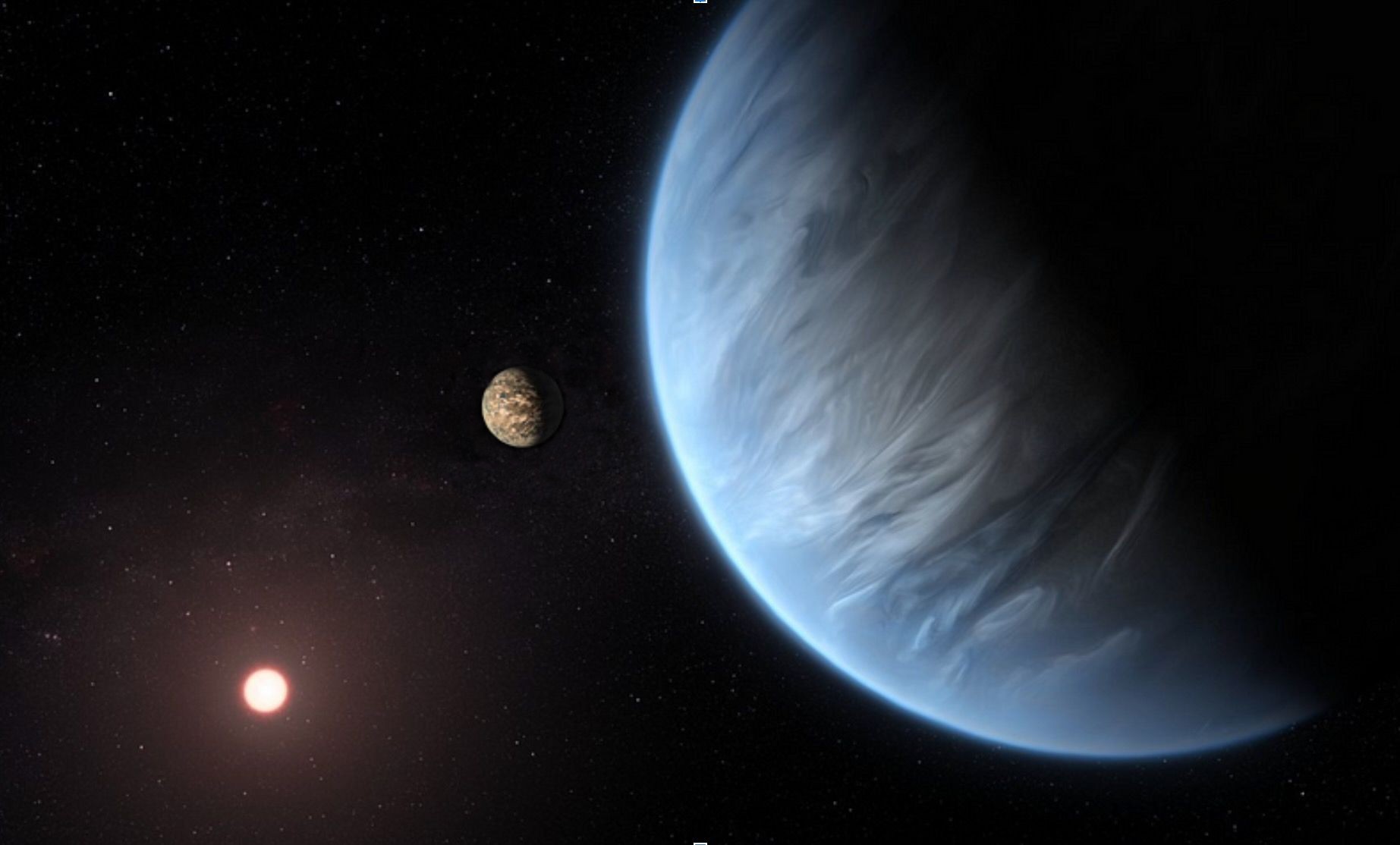

Astronomers have spotted two "super-Earth" exoplanets orbiting within the habitable zone of a nearby star.

Each of the newfound exoplanets is slightly larger than our planet, and both circle the same red dwarf star.

The exoplanets were spotted by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) as they crossed, or "transited," the face of their parent star, TOI-2095, which lies around 137 light-years from our solar system. This transit caused dips in the light from the star, and analyzing those dips revealed the presence, as well as some characteristics, of the two planets.

Related: Super-Earths: Exoplanets close to Earth's size

As a red dwarf, TOI-2095 is part of the largest family of stars in the universe. Despite being cooler than the sun, red dwarfs are known to experience violent outbursts of ultraviolet and X-ray radiation in their youth. This radiation could blow away the atmospheres of planets orbiting relatively nearby. As a result, scientists aren't sure if planets with a red dwarf's habitable zone — defined as the range of distances from a star in which liquid water could be stable on a world's surface — are actually hospitable to Earth-like life.

This makes the two planets orbiting in the habitable zone of this red dwarf — which have been designated TOI-2095 b and TOI-2095 c, respectively — tantalizing prospects for further investigation by astronomers.

The distance between the closest planet to the red dwarf, TOI-2095 b, and its star is around one-tenth of the average distance between the Earth and the sun. The exoplanet, which is 1.39 times wider than our planet but has up to 4.1 times its mass, takes around 17.7 Earth days to orbit the star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The system's second planet, TOI-2095 c, is a little farther out than its counterpart; takes 28.2 Earth days to orbit the red dwarf. This exoplanet has a diameter around 1.33 times that of Earth and has up to 7.5 times the mass of our planet. The planets likely have surface temperatures between 75 degrees Fahrenheit and 165 degrees Fahrenheit (24 to 74 degrees Celsius), researchers said.

The team behind the discovery, led by astronomer Felipe Murgas of the University of La Laguna in Spain, pointed out that the relatively long orbital periods of these two planets could provide crucial data that can help shed light on the processes that shape the composition of small planets orbiting red dwarfs.

The discovery of these two exoplanets further demonstrates the power of NASA's TESS mission. Since its launch in April 2018, the exoplanet hunter has found about 330 confirmed alien worlds, as well as more than 6,400 candidates that await follow-up study or analysis.

The team now intends to follow up on the discovery of the two super-Earths by making precise measurements of their radial velocity. Using these measurements, they can better estimate the mass of TOI-2095 b and TOI-2095 c, which would allow the densities of the planets to be more accurately determined. This could help astronomers discover if these two planets have managed to hang on to their atmospheres.

The team's study was posted on the paper repository arXiv last month.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.