Russian space chief weighs in on SpaceX's historic astronaut launch

Dmitry Rogozin discussed his 2014 "trampoline" comment and much more.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The head of the Russian federal space agency Roscosmos published a lengthy op-ed expressing mixed feelings about the recent SpaceX Demo-2 launch to the International Space Station (ISS).

Dmitry Rogozin's op-ed, which is available on the Rocosmos website and was previously published in Forbes, points toward Russia's future plans in space as the United States moves most of its crewed opportunities back to American soil.

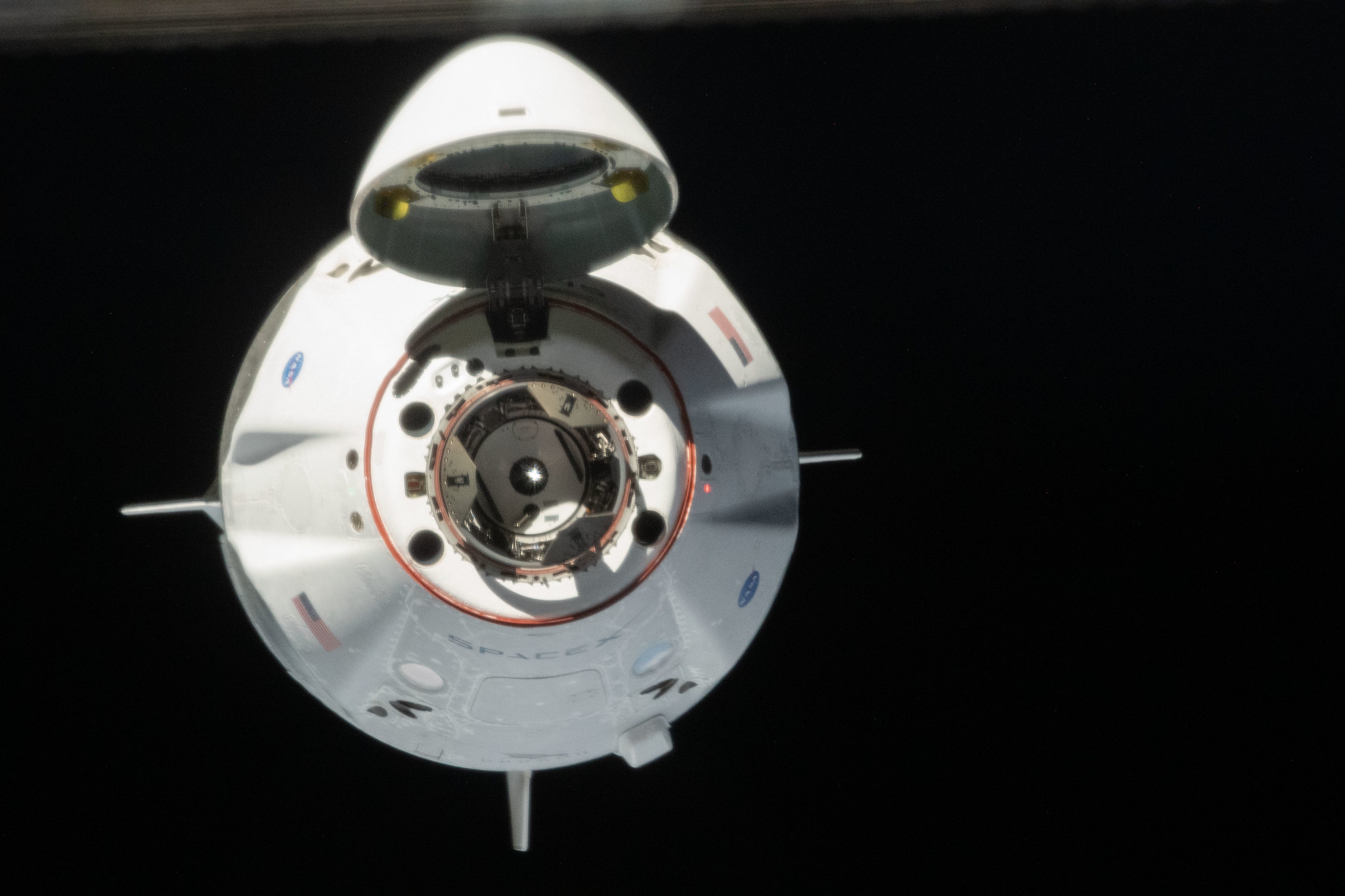

Demo-2 is the first of what will likely be many American crewed commercial spaceflights. Flights by SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule and, eventually, Boeing's Starliner spacecraft should largely replace the Russian Soyuz missions that NASA astronauts have relied upon since the space shuttle's retirement in 2011.

Related: In photos: SpaceX's historic Demo-2 test flight with astronauts

In 2014, Rogozin tweeted out a memorable remark, saying that, as Russians faced U.S. sanctions related to Russian actions in Crimea, American astronauts could use a trampoline to reach space instead of the Soyuz.

Shortly after Demo-2's May 30 launch, SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk referenced this barb, saying "The trampoline is working!" Rogozin initially said on Twitter that he loved Musk's joke and looks forward to further cooperation. But the new op-ed shows that Rogozin had more to share about the way astronauts are launched to space and the framework of international space cooperation.

The Russians were asked to step in with Soyuz seats for astronauts, Rogozin said, because the space shuttle program was closed down "as the result of its immense costliness and unforgivable failure rate."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Each NASA space shuttle orbiter used to carry as many as eight people at a time, although seven was a more typical crew capacity. The Russian Soyuz spacecraft has a capacity of three people.

The space shuttle program flew 135 missions between 1981 and 2011. Two of those missions ended in tragedy: The shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff in January 1986, and Columbia broke apart during re-entry in February 2003. Each tragedy killed seven astronauts.

The Soviet Union (a predecessor entity to Russia) lost four cosmonauts across two Soyuz mission failures in 1967 and 1971. While the Russians have had no spaceflight fatalities since then, there have been aborts.

Related: Russia's crewed Soyuz space capsule explained (infographic)

Most recently, a Russian Soyuz spacecraft experienced an abort in October 2018, after which the two crewmembers, NASA astronaut Nick Hague and cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin, walked away with no serious injuries. Following an investigation, addressing the problem and several uncrewed rocket flights to test the fix, the ISS coalition decided to proceed with the next crewed Soyuz launch, which went off without a hitch in December 2018.

"In crewed spaceflights, with people going into space aboard the vehicles, reliability is key to evaluate these technical means ensuring safety of the crews," Rogozin wrote in the op-ed. "Thus, the closure [of the space shuttle] came as a predictable and forced measure, as the Americans lost as many as two crews. Disasters and emergencies have already occurred in crewed cosmonautics, but none of them took this many lives at once."

The Russian Soyuz MS spacecraft that carries crews today, Rogozin said, is the "world's most reliable spacecraft" with 173 successful flights, and three aborts in 1975, 1983 and 2018 that allowed the crews to eject safely. The Soyuz rocket that carries the spacecraft overall has more than 1,900 successful launches, he added. "The U.S. engineers have yet to earn this reputation. I sincerely wish them luck," he said.

Rogozin said that NASA was "hectically searching for a solution" to replacing the space shuttle, a process that ultimately took about 17 years after the fatal Columbia accident in 2003. In 2004, the administration of President George W. Bush announced that the shuttles would be retired.

Commercial crew replacements began taking shape under the administration of President Barack Obama, with SpaceX and Boeing receiving spacecraft build contracts in 2014 after several competitive rounds involving other companies. The first launch of a crewed commercial vehicle was delayed by several years due to technical and funding issues, but ultimately happened with Demo-2 on May 30 of this year.

Simultaneous to commercial crew, NASA began to sketch out plans to move farther out into the solar system once again. NASA began developing the deep-space Orion crew capsule, in partnership with prime contractor Lockheed Martin, during the Bush-era Constellation program.

Orion has continued development into the present day, even though NASA's exploration focus shifted a few times under other administrations — from a moon-to-Mars Constellation program (Bush) to a "flexible destination" somewhere in deep space (Obama) to a moon-focused Artemis program (Trump). Orion made a successful uncrewed test flight in 2014 around Earth and is expected to launch on a (much-delayed) uncrewed trip around the moon and back no earlier than 2021. This moon mission will mark the debut of NASA's Space Launch System megarocket, which is also key to NASA's deep-space plans.

Related: Space Launch System: NASA's next-generation rocket

"Colossal funds were allocated to create three crewed spacecraft at once with the order distributed among several companies: Lockheed Martin (Orion moon spacecraft), SpaceX (Crew Dragon) and Boeing (Starliner)," Rogozin wrote.

He further added that the "generosity" of the U.S. government allowed SpaceX to receive a launch pad from NASA "at no expense," as well as a contract to build Crew Dragon and "NASA-paid scientific and technological groundwork and best engineering talents."

NBC News reported in 2014, however, that SpaceX would be responsible for the costs of maintaining and operating historic Launch Pad 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The story did not disclose contract amounts, nor say what other costs were associated with the 20-year lease agreement between NASA and SpaceX.

The 2014 contract that SpaceX received from NASA to build Crew Dragon was valued at $2.6 billion, and the contract was awarded following other development contracts between SpaceX and NASA.

Rogozin drew a few parallels between Crew Dragon and the costs of large programs in Russia, including a future lunar spacecraft and the relatively new Vostochny Cosmodrome that could eventually be used to launch Russian cosmonauts (who today launch from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.)

"The budget funds allocated to Elon Musk are three times bigger than the funding of the contract between Roscosmos and RSC Energia to develop a much more complex Russian lunar 'Oryol' spacecraft (Eagle)," Rogozin wrote.

"By the way, the Vostochny Cosmodrome costs 2.5 times cheaper than this purportedly private spacecraft – taking into account that the cosmodrome is being built in the Amur Taiga, [an] 8-hour-flight away from Moscow with no necessary workforce, nor construction machinery or logistic centers — all of that we had to bring or create there in the far east [of Russia]."

Rogozin continued with his reasoning about why Demo-2 had proved so popular among Americans. Hardly anyone attended the launch in person due to novel coronavirus-related quarantine restrictions, but the event was noted as NASA's most popular live event online.

The Roscosmos head said the Americans were "pretty anxious about the fact that they were fully dependent on the reliability of the Russian Soyuz" during the nine years it has ferried NASA astronauts into orbit. He said the launches happened "in full and with quality."

He added that the Russians kept the human space program going for all space station partners, while cutting Russian crews and experiments for the sake of the international partnership (presumably, to allow Americans and those using the American segment, such as Europeans, to take seats in the Soyuz.) "The Americans did not have to use the trampoline, as in my metaphor that got wind — we continued delivering their astronauts into space," Rogozin said.

Rogozin did not mention the Soyuz spacecraft found to have an air leak in orbit in 2018, although he did allude to the crew abort. He said the Russians were subject to mockery after the abort, and were not acknowledged for their role in keeping the space program going.

Rogozin also did not discuss the reliability of Russian Progress cargo ships to the space station that deliver vital supplies for astronauts. Several Progress missions failed during the last decade, and questions have been raised about the reliability of Russian Soyuz rockets as a result.

There also was an allusion to the cost of Soyuz seats, a tricky matter between NASA and Congress for years. Rogozin framed the cost per crew member seat as "honest money," a cost that continued to rise during the decade that NASA relied upon these seats to send people into space. The current cost for a Soyuz seat is estimated at $90 million, while a Crew Dragon seat is around $55 million, Rogozin said. But he said he still feels the Soyuz is a better deal.

"The new American spacecraft are more than double the weight of a Soyuz while offering only one additional seat," Rogozin said. He added that the size of the rockets needed to launch Crew Dragon (a SpaceX Falcon 9) or a Starliner (a United Launch Alliance Atlas V) are much heavier than what is required for Soyuz, which uses a medium-class Soyuz-2.1a rocket. He argued that on that comparison, Russian launches remain cheaper than American launches.

"The sirs seem to confuse launch cost price and launch service price that is formed by the market," Rogozin said. "Hence, I insist that Soyuz MS spacecraft with the Soyuz-2.1a carrier rocket was and still remains unchallenged — whatever our competitors say."

Rogozin also provided some hints about the future Russian space program as the U.S. moves more into commercial crew. He pointed to the long space history Russia has; for example, Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet Union cosmonaut, was the first person to reach space in 1961. "We remain dominant," Rogozin added, saying Musk's flight was more a slight against Boeing than Russia. "This war is theirs, but not ours," he said.

Some of the Russian actions Rogozin highlighted include:

- Continuing to refine the Soyuz and to build a "new and more advanced spacecraft."

- Moving forward on development of the more environmentally friendly Angara rocket, which he said was previously delayed due to complicated land-use discussions. He pledged to build a "National Space Center buildings complex" by 2022 and a "modern, state-of-the-art engineering center" for Russian rocket engineers. Angara will be ready to lift off in 2023 from Vostochny, he said, in time to replace the Proton rocket that will be banned in 2025 due to environmental concerns.

- Finding more ways to continue being competitive in the industry. Rogozin said one great success was cutting the flight time to the International Space Station, with some recent Progress cargo ships reaching ISS in just over three hours (as opposed to the usual days). Ways to remain competitive, he said, include launching Angara, continuing development on tech such as methane-powered engines and nuclear-powered tugs for deep space, creating a two-stage Soyuz light-heavyweight class rocket for testing in 2023, and developing a super-heavy booster to launch future cosmonauts aboard the Oryol crewed spacecraft. Oryol should have flight tests in 2023 and will start flying to the ISS in 2025, he said.

- Building new ISS modules that will be called Nauka, Prichal (also known as Uzlovoy) and a Science Energy Module, all of which are expected to increase the scientific experiment capacity on the Russian side of the station. These modules will also help in "strengthening [Russia's] independence from the partners," Rogozin said.

- Continuing work on other missions and projects, such as military missions, expanding Vostochny's capacity to launch missions, launching the Luna-25 mission expected to fly to the moon in 2021, building and launching a lunar orbiter and lunar module to do further moon exploration, and renewing the GLONASS global navigation satellite constellation in Earth orbit.

- Committing to keep spacecraft spending lean, including a pledge to "radically cut the costs and excessive nonproduction workers." The ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Rogozin added, has shown Roscosmos which employees may be able to work remotely continuously.

- Focusing on "profile" projects in the near future, including rocket construction, satellite construction, ground space infrastructure and science. Roscosmos will maintain independent design bureaus and engineering centers, Rogozin added, for "maintaining the competitive spirit between them in a bid for new projects." He also pledged greater technology transfer, in part by creating joint technology competence centers.

- Roscosmos: Russia's space centers and launch sites in pictures

- Soyuz spacecraft: Backbone of Russia's space program

- 'The trampoline is working!' The story behind Elon Musk's one-liner at SpaceX's big launch

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.