Orion spacecraft: NASA's next-gen capsule to take astronauts beyond Earth orbit

Learn about Orion spacecraft's interior and its role in lunar missions during the 2020s, including planned moon landings.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The Orion spacecraft (more formally, the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle) is NASA's vehicle of choice to take astronauts to the moon, a future lunar space station and potentially, on to Mars.

The spacecraft has already passed one major flight in space in 2014 and is expected to take on a second journey shortly with the Artemis 1 mission, expected to launch no earlier than May 2022. An orbital mission and a landing mission are then expected later in the 2020s.

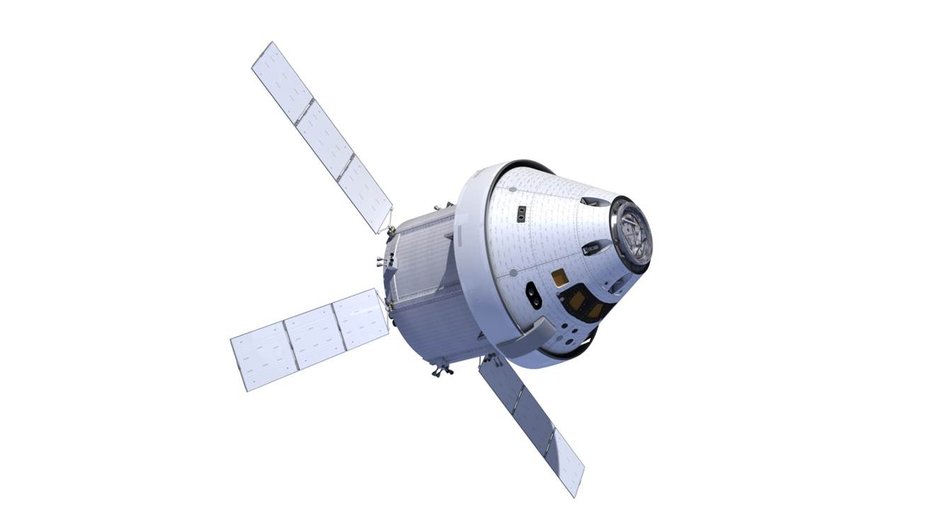

Similar in shape to the Apollo spacecraft, Orion is designed to carry up to four astronauts to destinations such as the moon or Mars. Orion is a significant upgrade from Apollo — the spacecraft is newer and much larger than Apollo, and sports electronics decades more advanced than what Apollo's astronauts used to fly to the moon.

Orion spacecraft Fast facts

- Crew: 4

- Height: 50 feet/15 meters (including launch abort system)

- Diameter (base): 17 feet (5.2 meters)

- Maximum number of days in space: 21

- Mass (Artemis 2): 17,000 lbs (7,770 kg)

- Solar arrays: 4

Orion spacecraft development history

Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor for the spacecraft. The company began work on the spacecraft in 2004 during a competition for the contract, which was valued at up to $8.15 billion when Lockheed Martin won it in August 2006.

Orion was originally built for NASA's Constellation program that was intended to bring humans to the International Space Station, the moon and, ultimately, Mars. The program was canceled in 2010 after President Barack Obama's administration requested that NASA focus on other goals.

At that point, NASA had already spent $5 billion on developing Orion and Lockheed had been working on the spacecraft for about six years. In early 2011, NASA hinted that the Orion spacecraft could be repurposed for their new directive. The agency followed up with a plan for the Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle — one that was relatively close to the previous Orion spacecraft design, but instead could be used for the new mandate.

"We made this choice based on the progress that's been made to date," Doug Cooke, associate administrator for NASA's Exploration Systems Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C., said to reporters on May 24, 2011. "It made the most sense to stick with [the Orion design]." [The Orion Capsule: NASA's Next Spaceship (Photos)]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Orion persisted through its development as NASA pivoted program goals yet again, when U.S. President Donald Trump tasked the agency with prioritizing moon landings over deep space excursions for a planned 2024 landing. The program, eventually known as Artemis, expects to put boots on the moon somewhat after that deadline, which was not met due to numerous issues explained below.

The Joe Biden administration committed to continuing Artemis, after coming to office in 2021. A next major stage in spacecraft development will be the Artemis 1 mission, which will see how well Orion performs in a cislunar environment. That will allow engineers to ready the spacecraft for human missions later in the 2020s.

Besides the flight tests, Orion has proceeded through many years of ground testing to ensure its readiness for space. Some recent milestones (after its first, successful spaceflight) include completing parachute testing in 2018, acing a key propulsion test in 2019, and performing splashdown "drop" testing in a pool in 2021 to prepare for the first humans aboard Artemis 2.

Orion spacecraft design and interior

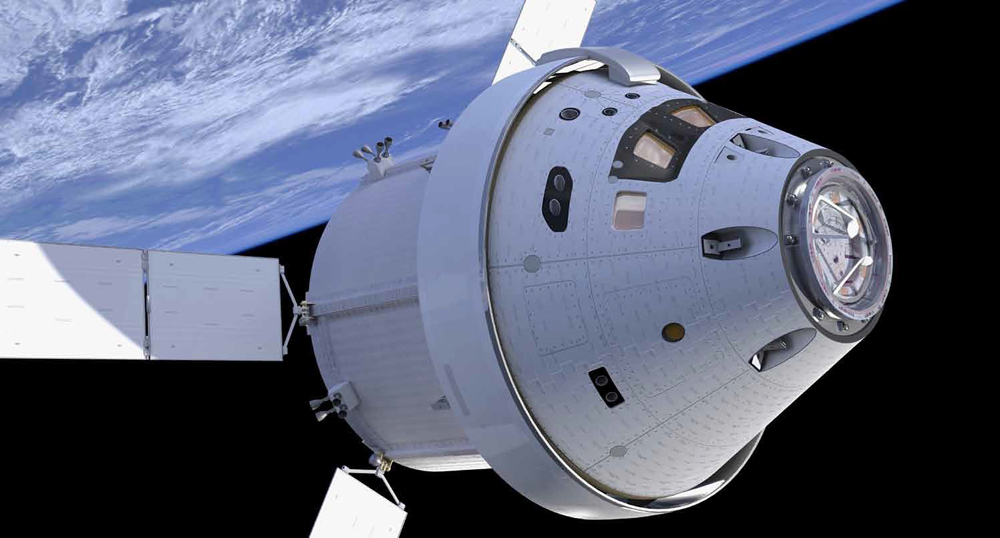

The Orion spacecraft consists of a gumdrop-shaped capsule and service module, which together are about 26 feet (8 meters) long with a diameter of 16.5 feet (5 m). The spacecraft's habitable volume is 316 cubic feet (8.95 cubic meters), which is about 1.5 times larger than the Apollo spacecraft.

Orion's crew module is just one of several components of the spacecraft. Orion also contains a launch- abort system to pull astronauts away from the spacecraft with escape rockets should something go wrong during launch.

The service module, built by the European Space Agency, contains solar panels for electricity, oxygen for breathing and rocket engines to propel the spacecraft. Orion also includes a spacecraft adapter (which shields the service module during launch) and an instrument unit that includes the guidance and control system for the booster. [Infographic: Orion Explained: NASA's Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle]

Orion's interior will include a sleek set of screens for astronauts to keep an eye on key systems and mission progress, in consultation with Mission Control at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"Because astronauts of different sizes will be sent to the Moon in Orion, the display panels and chairs need to work for 99 percent of people," NASA wrote. "That means making the bottom panels of the seats adjustable, and arranging panels so that the smallest or largest of astronauts can reach all the controls."

Window shades can be deployed on the windows to block out sunlight, and sleeping bags will allow astronauts to comfortably strap themselves to a spot in the spacecraft for weightless sleep.

NASA is pulling from decades of research on the International Space Station, the shuttle and earlier programs to keep the astronauts safe and comfortable. For example, acoustics specialists were consulted to make sure equipment was humming at a comfortable level, and emergency equipment is stored within easy reach in case a fire or sudden depressurization occurs.

Orion spacecraft's Exploration Flight Test-1

The first space mission of Orion was Exploration Flight Test-1, also known as EFT-1. That saw Orion undergo a space test for 4.5 hours, soaring as high as 3,600 miles (5,800 km) for two orbits of Earth.

The spacecraft was fitted with about 1,200 sensors to record essential data to inform future design, such as stresses, temperature, pressure, acceleration and vibration. It also came with ultrawide field cameras to record flight events in high definition.

Since SLS was still under construction, Orion rode to space aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy booster. The rocket was still powerful enough to push Orion further into space than any humans had been since 1972, when Apollo 17 made a moon landing.

Orion also experienced the inner Van Allen Belt, a zone of radiation trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field. Surviving the radiation here was key for the protection of future astronauts, who will need to pass through this zone to make it to the moon.

Orion program pivot

Shortly after EFT-1 splashed down, NASA said the flight had been a success. The major systems worked well; also, roughly 55 percent of the capsule's technology that is deemed essential for crewed missions passed muster during the flight. The agency was hoping to fly a second test of Orion as soon as 2018, on board SLS.

But numerous challenges arose in getting ready for Artemis 1. For example, NASA was tasked with changing program approaches as the Donald Trump presidency reached office. Orion was originally imagined to bring astronauts to multiple destinations in deep space, but Trump directed NASA to pivot to a moon landing to as soon as 2024, necessitating that the spacecraft be repurposed for lunar work.

Additionally, SLS development fell behind schedule due to multiple issues. The eruption of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 created supply chain problems and physical distancing necessities, both of which slowed down manufacturing and testing.

SLS also had several technical issues in completing a "green run" series of testing, and then had to overcome problems found with the core engines. Issues like these pushed the debut date of SLS to 2022, inducing an eight-year gap between Orion's first and second test flights.

Orion spacecraft and Artemis 1

As of this writing, Artemis 1 is expected to start its mission no earlier than May 2022. It will be the first mission of NASA's SLS in partnership with the Orion spacecraft, which will be on its second program mission.

Orion will take a much further journey this time around, however, going on a a 236,000-mile-long (380,000-kilometre-long) journey to the moon. According to NASA, "Orion will stay in space longer than any ship for astronauts has done without docking to a space station, and return home faster and hotter than ever before."

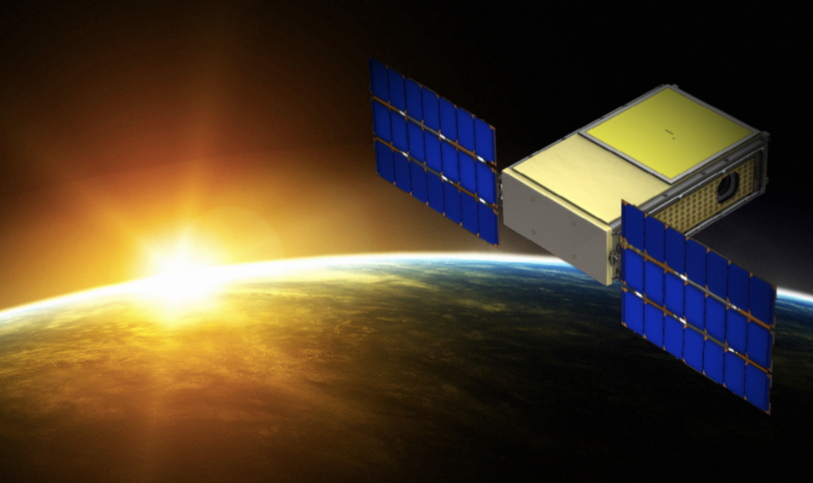

One of the mission's first jobs, upon leaving Earth orbit, will be to eject several tiny satellite hitchhikers. An example is BioSentinel, which carry yeast samples into deep space to study how radiation affects living organisms. The applications will be carried forward to Artemis 2 and other missions with humans.

As Orion swoops around the moon, it will be accompanied by several mannequin-type devices to give even more information on how the lunar environment affects humans.

"Commander Moonikin Campos," named after Apollo 13 engineer Arturo Campos in a NASA contest, will fly in the commander's seat wearing the same Orion Crew Survival System spacesuit that astronauts will don later in the program. Also on Campos will be radiation sensors and instrumentation for vibration and acceleration data.

Two simulated female astronauts will fly on other Orion seats, from the German space agency (DLR). One of them, Zohar, is wearing a a radiation-shielding vest called StemRad while the other, Helga, will serve as a control with no such protection.

The mission will include several Lego astronauts and even Snoopy, the famous "Peanuts" dog who also served as a moniker for Apollo 10 lunar spacecraft that approached the surface of the moon. This time around, he will be a "zero-gravity indicator" and will wear the Orion spacesuit in miniature.

Orion will remain in a retrograde orbit for between six and 19 days before getting a gravity assist from a return towards the moon. The assist will help Orion fly back to Earth, on a journey that should take another nine to 19 days.

Finally, Orion will make a high-speed re-entry similar to what was tested during Orion's first test flight in 2014, when the spacecraft got as high as 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometers) above Earth. It will descend for an ocean splashdown under parachutes, and the data will later be analyzed to get ready for human missions.

Orion, Artemis 2 and Gateway

Assuming that Artemis 1 is completed with no major issues, Artemis 2 will be the next major moon mission. Artemis 2 is expected to launch around May 2024 (compared with a previous goal of September 2023, induced by delays to Artemis 1.)

The mission will see a group of astronauts ride around the moon in the Orion spacecraft. NASA administrator Bill Nelson told reporters in 2021 that Artemis 2 will travel "further than humans have ever been, probably 40,000 miles [about 64,000 kilometers] beyond the moon," before returning to Earth.

The crew for Artemis 2 has not yet been named. NASA has a set of astronauts prequalified for Artemis missions, known as the "Artemis team." The group includes women and several non-white astronauts, which will distinguish the Artemis program from its predecessor, Apollo, that saw 12 white men land on the moon.

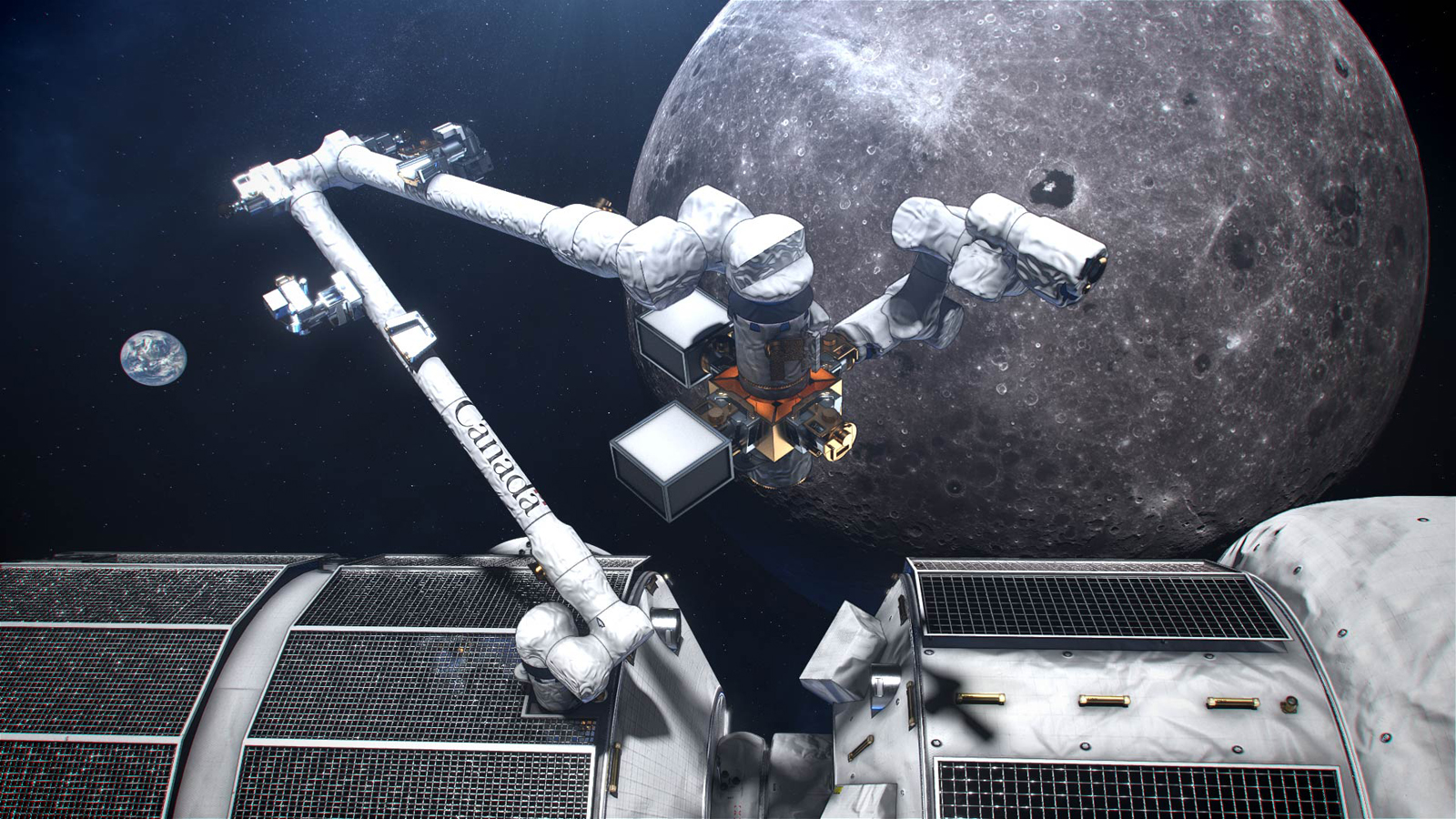

Also on the team will be a so-far unnamed Canadian Space Agency astronaut, as a thank-you for the country's contribution of Canadarm3. This robotic arm will continue a series of Canadarms that were active during the space shuttle and now, the International Space Station era. Canadarm3 will have artificial intelligence embedded in its software to do repairs and maintenance.

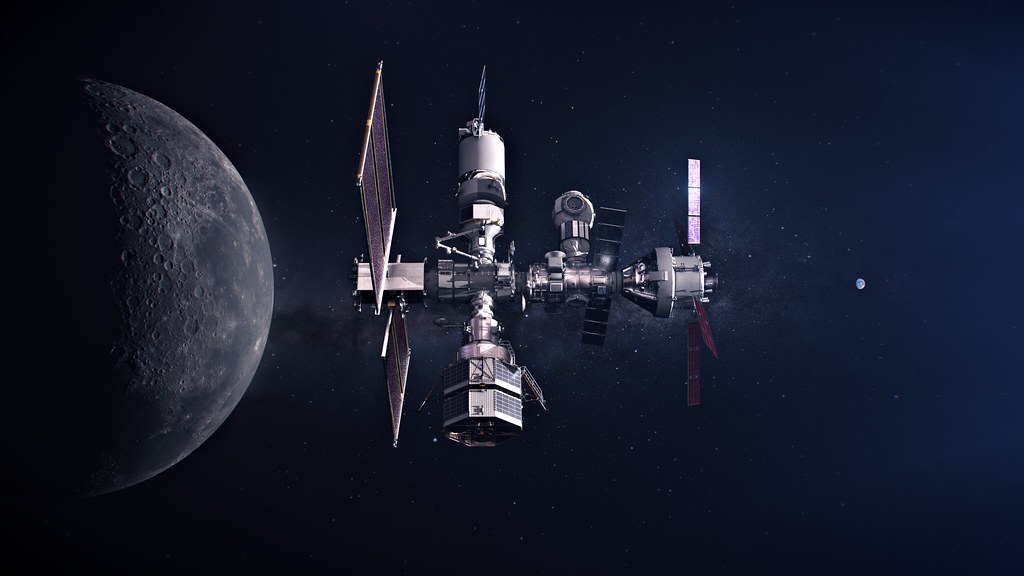

The arm will fly aboard a planned space station NASA plans to put near the moon, called Gateway. It will host crews for between one and three months to do science, to assist with landing missions and to test out technology such as telerobotics.

Gateway's orbit will be a "near rectilinear halo orbit" (NRHO). It will range between 1,860 miles and 43,500 miles (3,000 and 70,000 kilometers) from the surface of the moon, according to the European Space Agency This will allow Gateway to experience a minimum of eclipses for consistent solar power.

Orion and Artemis 3

Artemis 3 will see a crew of astronauts, including the first woman and potentially the first person of color, alight on the moon's surface. The crew is expected to touch down somewhere in the south pole, which is a region unexplored by people or missions to date. But it is a potentially valuable zone, full of volatiles such as water that could be harvested for mining or astronaut needs.

NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, which seeks to send a set of private landers and experiments to the moon, plans to explore the region in more detail in the coming years. For example, NASA's Polar Resources Ice-Mining Experiment-1 (PRIME-1) is expected to land at Shackleton Crater aboard an Intuitive Machines Nova-C lander.

NASA will use what it learned from PRIME-1 to prepare for a more ambitious lunar rover mission, the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER). This mission, targeted for a 2023 landing, is expected to touch down just west of Nobile, a crater near the moon's south pole.

The moon landing for Artemis 3 is expected no earlier than 2025, although NASA's Office of the Inspector General has repeatedly expressed pessimism about that deadline and now says it will be at least 2026. For one thing, technology and logistics problems have already pushed back Artemis 1. Other things are making the timeline for Artemis 3 fuzzy, too.

The agency's development of next-generation spacesuits, called the Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit (xEMU), is facing delays. Budgetary concerns and a 20-month delay in designing, verifying and testing the suits are among the problems cited. NASA also decided to pivot much of the work to a contractor to save costs, but which is expected to add time to the process.

Another worry is the Human Landing System (HLS) that is supposed to be readied by SpaceX. The program was delayed seven months in 2021 due to protests and a lawsuit by Blue Origin last year (all resolved by November) concerning NASA's sole-source award.

The Artemis program's ballooning cost is also at issue. The first four Artemis missions are expected to cost $4.1 billion each, according to a November 2021 OIG audit.

References

"Artemis." NASA. (n.d.) https://www.nasa.gov/specials/artemis/.

"NASA's Management of the Artemis Missions: Report No. IG-22-003." NASA Office of the Inspector General. (2021, Nov. 15). https://oig.nasa.gov/docs/IG-22-003.pdf.

"Orion." Lockheed Martin. (2022.) https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/orion.html.

"Orion Quickfacts." NASA Johnson Space Center. (n.d.) https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/fs-2014-08-004-jsc-orion_quickfacts-web.pdf.

"Orion Spacecraft." NASA. (2021, July 9). https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/orion/index.html

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.