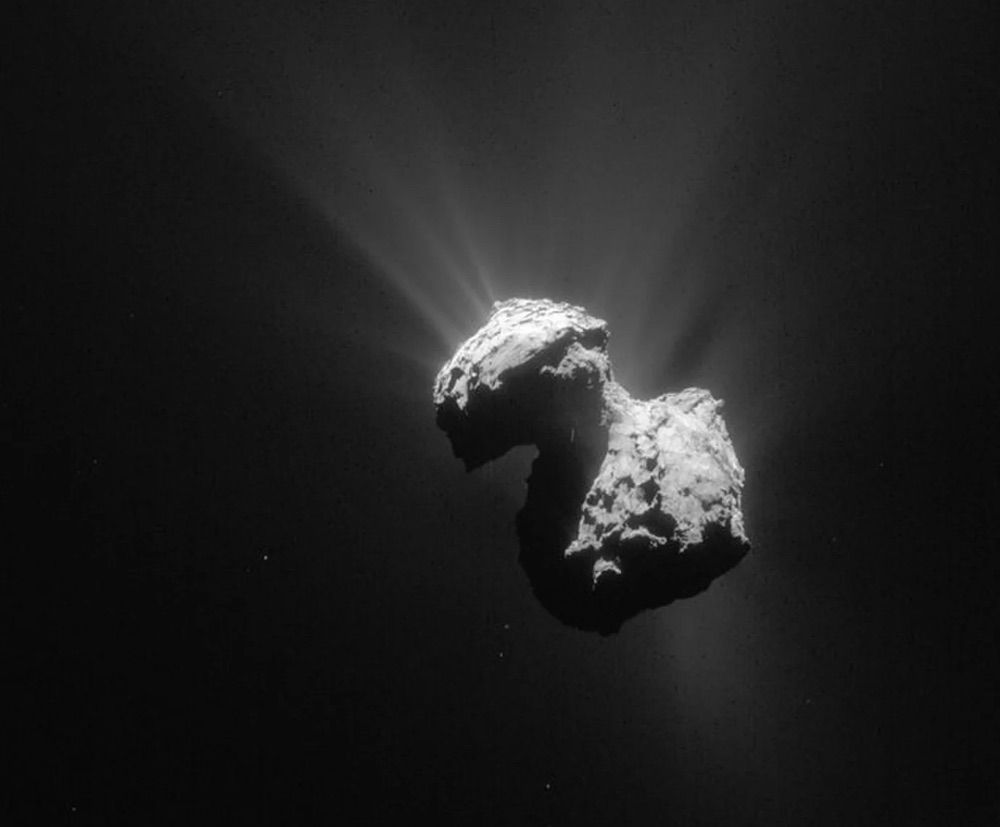

Rosetta's 'rubber ducky' comet changed color as it neared the sun. Here's why.

A solar pass made Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko much bluer.

The Rosetta spacecraft's rubber ducky comet has slowly changed color as it moved through space, from red to blueish and then red again.

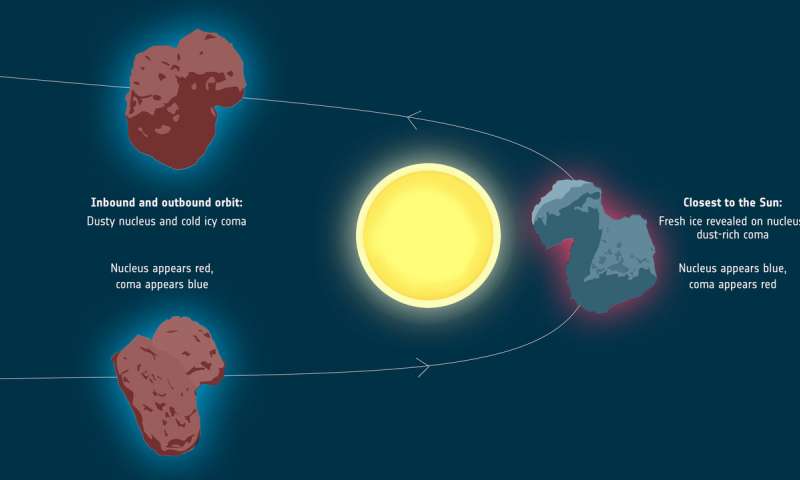

According to a new paper published Feb. 5 in the journal Nature, the color change is a signal of a water cycle on the first comet ever visited by a human probe. As comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (Rosetta's comet's full name) crossed a boundary in its orbit around the sun, known as the frost line, ice began to turn to gas on its surface, sublimating away into space. When that happened, an outer layer of dirty ice on the comet's surface, full of reddish dust, blew away into the vacuum, revealing the bluer, cleaner ice underneath.

It's as if the comet had its own "seasons," the researchers wrote.

Related: Spectacular comet photos (Gallery)

The changes described here took place over a long time, between January 2015 and August 2016, the researchers wrote. That was the midpoint of Rosetta's time at the comet. The European Space Agency orbiter arrived on Aug. 6, 2014, and crashed into the comet itself on Sept. 30, 2016.

There were, in fact, two opposite cycles at work around the comet, the researchers wrote. Approaching the sun and crossing the frost line — about three times Earth's distance from the sun — exposed that more pristine, blue surface. But the coma, a hazy region around the solid nucleus made of dust and gas, got redder.

What caused that reddening? "Grains made of organic material and amorphous carbon in the coma" the researchers wrote.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In other words, all those microscopic grains of carbon-rich dust that melted off the comet's surface stopped reddening the surface and started reddening the coma.

Once the comet moved away from the sun again, its solid core reddened again as dust once again settled on the surface of the nucleus.

These changes, viewed over months from a color-sensitive camera that Rosetta trained on the comet, would not have been visible from Earth, the researchers said in a statement. Earth-based telescopes can't precisely distinguish a faraway comet's nucleus and coma. And comets often go through temporary changes that might confuse a telescope observing a comet in brief snapshots. Rosetta's two-year observation allowed for a more robust analysis of long-term trends.

Even though Rosetta's mission is over, the researchers wrote, there's still lots of data left to comb through, and more discoveries of this kind will likely be revealed.

- The 12 strangest objects in the universe

- Crash! 10 biggest impact craters on Earth

- 15 amazing images of stars

Originally published on Live Science.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.