The strange story of the grave of Copernicus

Nicholas Copernicus was the astronomer who, five centuries ago, explained that Earth revolves around the Sun, rather than vice versa.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

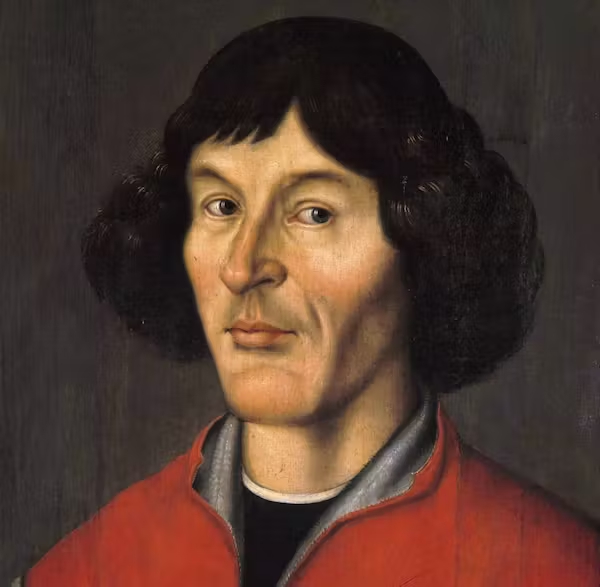

Nicholas Copernicus was the astronomer who, five centuries ago, explained that Earth revolves around the Sun, rather than vice versa. A true Renaissance man, he also practised as a mathematician, engineer, author, economic theorist and medical doctor.

Upon his death in 1543 in Frombork, Poland, Copernicus was buried in the local cathedral. Over the subsequent centuries, the location of his grave was lost to history.

Who was Copernicus?

Nicholas Copernicus, or Mikołaj Kopernik in Polish, was born in Toruń in 1473. He was the youngest of four children born to a local merchant.

After his father’s death, Copernicus’s uncle assumed responsibility for his education. The young scholar initially studied at the University of Kraków between 1491 and 1494, and later at Italian universities in Bologna, Padua and Ferrara.

After studying medicine, canon law, mathematical astronomy, and astrology, Copernicus returned home in 1503. He then worked for his influential uncle, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, who was the Prince-Bishop of Warmia.

Copernicus worked as a physician while continuing his research in mathematics. At that time, both astronomy and music were considered branches of mathematics.

During this period, he formulated two influential economic theories. In 1517, he developed the quantity theory of money, which was later re-articulated by John Locke and David Hume, and popularised by Milton Friedman in the 1960s. In 1519, Copernicus also introduced the concept now known as Gresham’s law, a monetary principle addressing the circulation and valuation of money.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Copernican model of the universe

The cornerstone of Copernicus’s contributions to science was his revolutionary model of the universe. Contrary to the prevailing Ptolemaic model, which maintained that Earth was the stationary centre of the universe, Copernicus argued that Earth and other planets revolve around the Sun.

Copernicus was further able to compare the sizes of the planetary orbits by expressing them in terms of the distance between the Sun and Earth.

Copernicus feared how his work would be received by the church and fellow scholars. His magnum opus, “De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium” (On the Movement of the Celestial Spheres), was only published just before his death in 1543.

The publication of this work set the stage for groundbreaking shifts in our understanding of the universe, paving the way for future astronomers such as Galileo, who was born more than 20 years after Copernicus’s death.

The search for Copernicus

The Frombork Cathedral serves as the final resting place of more than 100 people, most of whom lie in unnamed graves.

There were several unsuccessful attempts to locate Copernicus’s remains, dating as far back as the 16th and 17th centuries. Another failed attempt was made by the French emperor Napoleon after the 1807 Battle of Eylau. Napoleon held Copernicus in high regard as a polymath, mathematician and astronomer.

In 2005, a group of Polish archaeologists took up the search.

They were guided by the theory of historian Jerzy Sikorski, who claimed that Copernicus, serving as the Canon of Frombork Cathedral, would have been buried near the cathedral altar for which he was responsible during his tenure. This was the Altar of Saint Wacław, now known as the Altar of the Holy Cross.

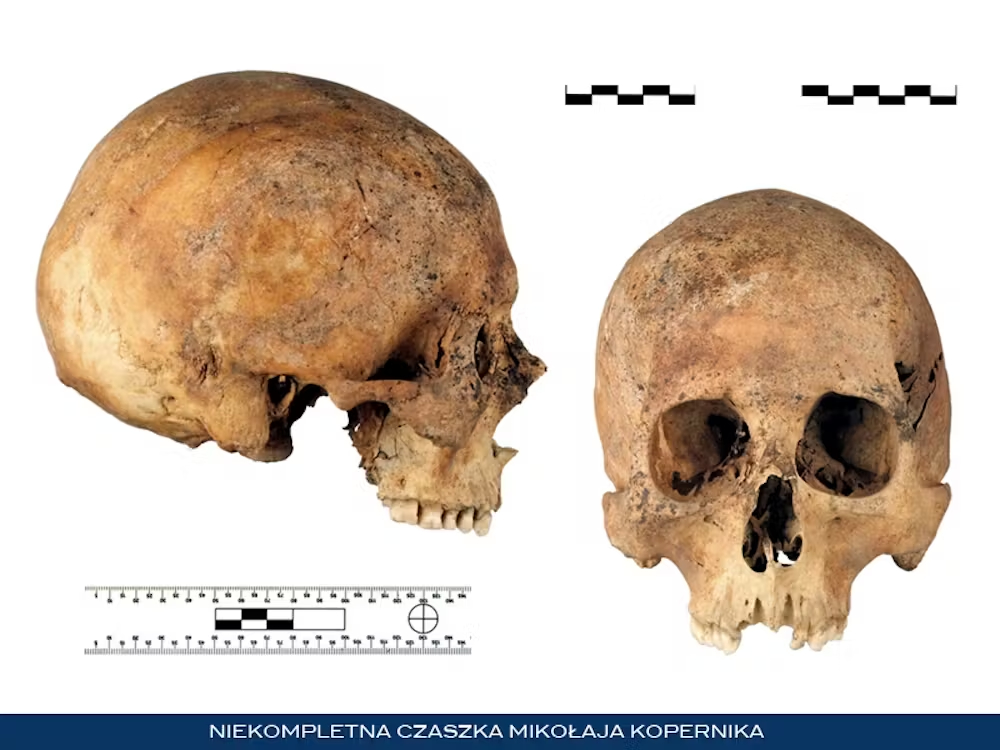

Thirteen skeletons were discovered near this altar, including an incomplete skeleton belonging to a male aged between 60 and 70 years. This particular skeleton was identified as the closest match to that of Copernicus.

Forensic science

The skull of the skeleton served as the basis for a facial reconstruction.

In addition to morphological studies, DNA analysis is often used for the identification of historical or ancient remains. In the case of the presumed remains of Copernicus, a genetic identification was possible due to the well-preserved state of the teeth.

A significant challenge lay in identifying a suitable source of reference material. There were no known remains of any relatives of Copernicus.

An unlikely find

In 2006, however, a new source of DNA reference material came to life. An astronomical reference book used by Copernicus for many years was found to contain hair among its pages.

This book had been taken to Sweden as war booty following the Swedish invasion of Poland in the mid-17th century. It is currently in the possession of the Museum Gustavianum at Uppsala University.

A meticulous examination of the book revealed several hairs, thought likely to belong to the book’s primary user, Copernicus himself. Consequently, these hairs were assessed as potential reference material for genetic comparison with the teeth and bone matter recovered from the tomb.

The hairs were compared with the DNA from the teeth and bones of the discovered skeleton. Both the mitochondrial DNA from the teeth and the skeletal sample matched those of the hairs, strongly suggesting that the remains were indeed those of Nicholas Copernicus.The multidisciplinary effort, involving archaeological excavation, morphological studies and advanced DNA analysis, has led to a compelling conclusion.

The remains discovered near the Altar of the Holy Cross in Frombork Cathedral are highly likely to be those of Nicholas Copernicus. This monumental find not only sheds light on the final resting place of one of the most influential figures in the history of science, but also showcases the depth and sophistication of modern scientific methods in corroborating historical data.

Darius is a historian of East Central Europe with broad interest in cultural aspects of transmission of ideas across time and space. He is interested in global history and pursues interdisciplinary research and teaching subjects which examine history from a global perspective.

He is researching the common patterns which emerged across all cultures, in aspects of world history which have drawn people together - the patterns that reveal the diversity of the human experience.

Darius has a strong research interest in education. In addition to the interest in curriculum (design and development, and policy implementation and evaluation), he researches the nexus between research orientated teaching and learning and the disparity between the methodology of teaching of a discipline like history at secondary and tertiary levels.

After a decade of teaching outside metropolitan centres he is working collaboratively on the issues affecting education in regional settings, specifically on regional culturally, linguistically and economically diverse (CLED) communities of learning and the use of emerging technologies and the issues affecting funding for humanities.