China's Tianwen-1 lowers its orbit around Mars to prepare for rover landing

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

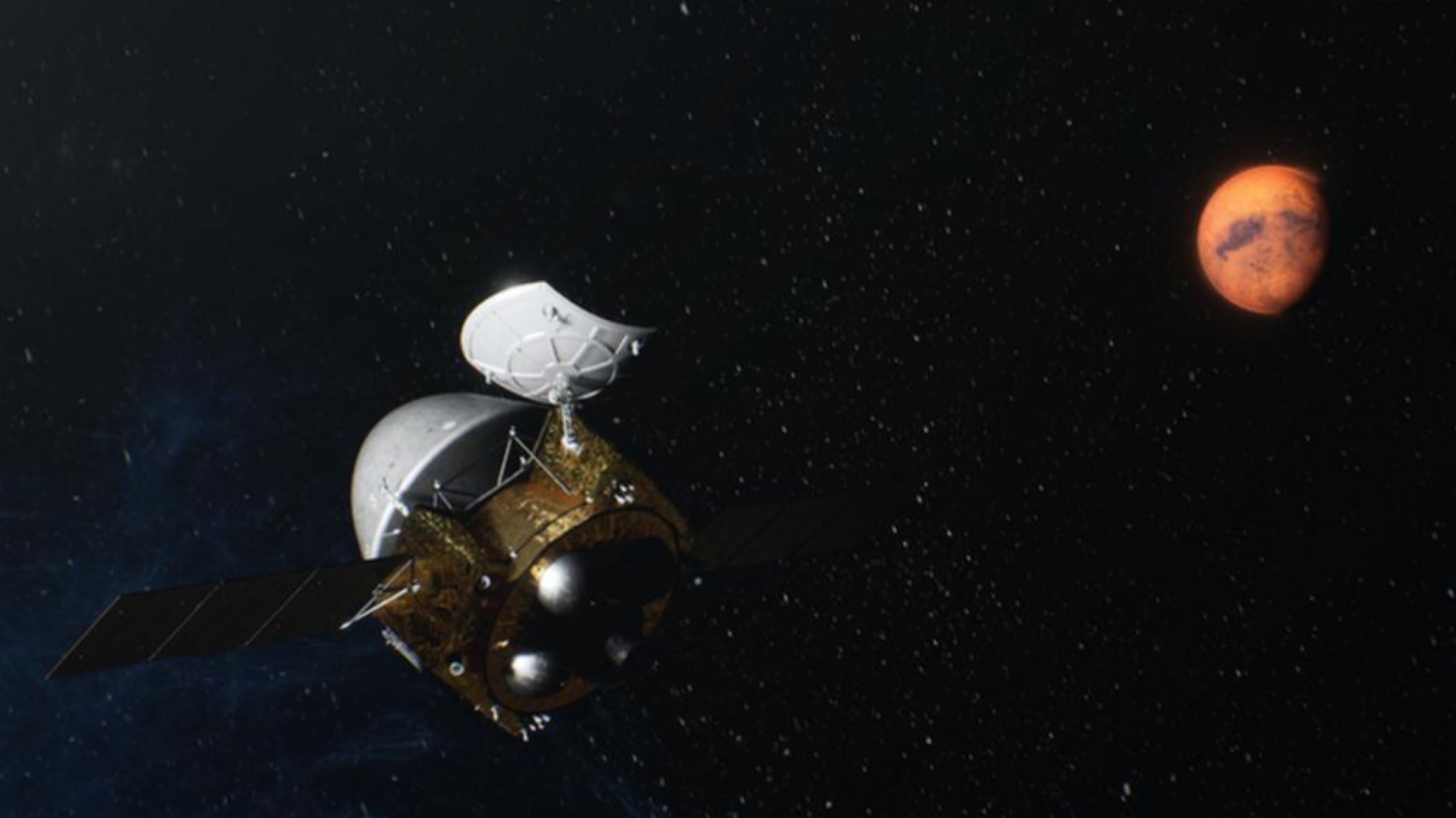

China's Tianwen-1 spacecraft has trimmed its orbit around Mars to allow the spacecraft to analyze the chosen landing region on the Red Planet.

After the burn, which occurred on Tuesday (Feb. 23), Tianwen-1 is now in position to begin imaging and collecting data on primary and backup landing sites for the mission's rover, which will attempt to touch down in May or June.

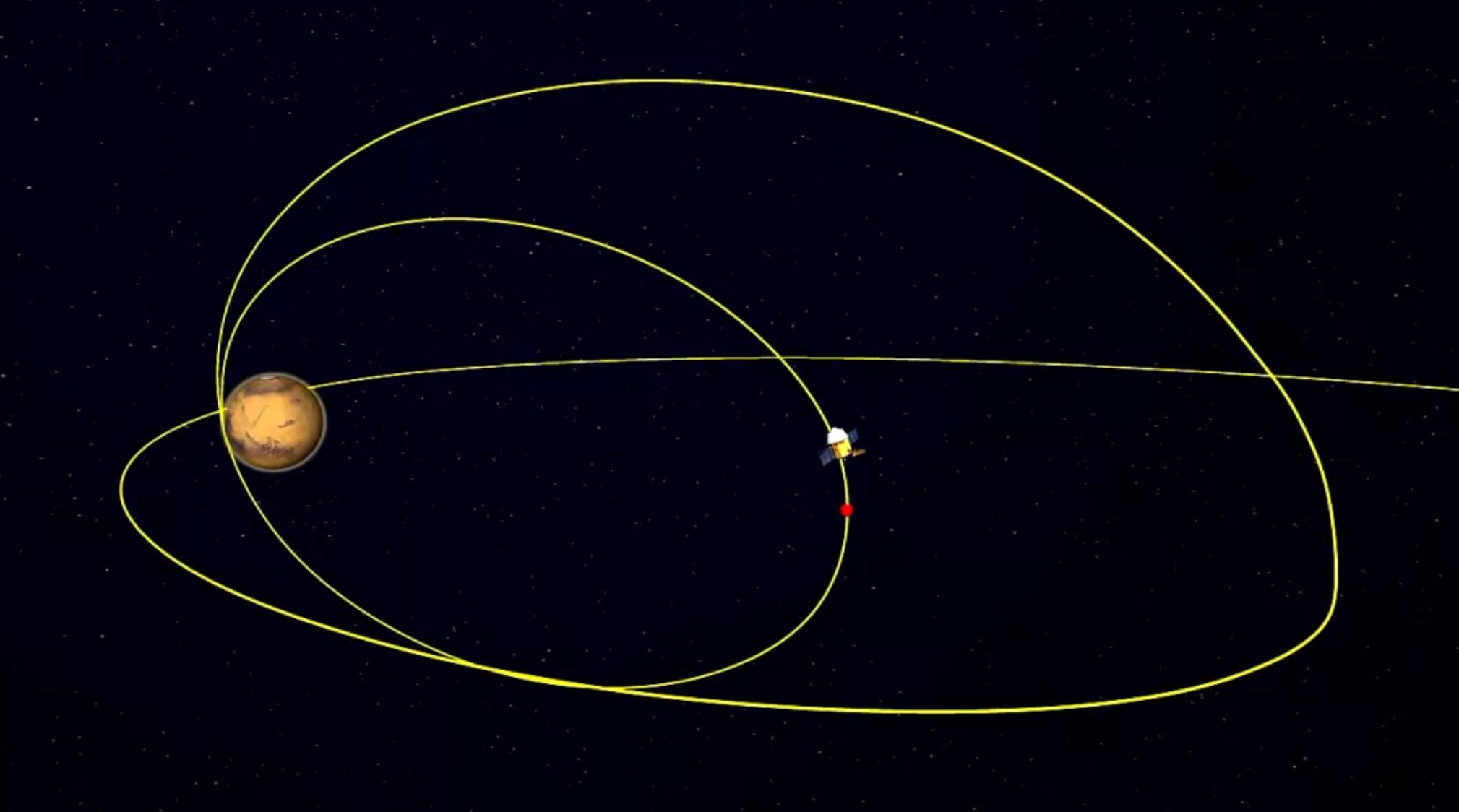

Tianwen-1, China's first independent interplanetary mission, consists of an orbiter and rover, which have been in Mars orbit as a single spacecraft since Feb. 10. The latest engine burn, at 5:29 p.m. EST Tuesday (2229 GMT, 06:29 Beijing time Wednesday), executed during the spacecraft's closest approach to Mars, greatly reduced its apoapsis, or farthest point from the planet.

Related: The latest news about China's space program

Tianwen-1's new "parking orbit" takes the spacecraft as close as 170 miles (280 kilometers) to Mars and as far away as 37,000 miles (59,000 km).

The mission orbiter is now firing up its camera and science payloads, preparing to assess the landscape and dust conditions at the primary landing site, situated within an area of Utopia Planitia, a vast plain on the Red Planet.

The "parking orbit" will allow the orbiter to capture sharp images of the targeted landing site, potentially returning images with a resolution of 20 inches (50 centimeters) per pixel.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tianwen-1 will photograph the region on multiple occasions to evaluate the topography and dust conditions in the landing zone, Tan Zhiyun, deputy chief designer of the Mars probe with the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST), told CCTV+. "We will figure all these information out in preparation for a safe landing," Tan said.

Each orbit takes about two Earth days to complete, so China may be able to capture and release the probe's first high-resolution images of the Martian surface in the following days.

Understanding local conditions is also very important for the operation of the mission's roughly 530-lb. (240 kilograms) solar-powered rover. Martian dust can pose major threats to solar-powered spacecraft on the surface; NASA's Opportunity rover lost contact with Earth in 2018 during just such a global dust storm.

The Tianwen-1 rover is contained within an aeroshell attached to the orbiter. This conical structure will both protect and slow the rover during its fiery, hypersonic entry into the Martian atmosphere at the start of the landing attempt. A supersonic parachute will further slow the rover before retropropulsion engines provide the final deceleration for the soft landing.

The rover carries science payloads to investigate surface soil characteristics and mineral composition and to search for potential water ice with a ground penetrating radar. The rover is designed to operate for 90 Mars sols (92 Earth days) with the Tianwen-1 orbiter serving to relay communications and data between the rover and the Earth. The orbiter is designed to operate for a total of one Mars year, or about 687 Earth days.

Tianwen-1 is one of three missions that have just reached Mars. Tianwen-1 entered orbit a day after the United Arab Emirates' Hope probe managed the same feat and a week before the spectacular landing of NASA's Perseverance rover.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.