You won't see interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS zoom closest to the sun on Oct. 30 — but these spacecraft will

Perihelion takes place on Oct. 30, when the interstellar comet should in theory be at its most active.

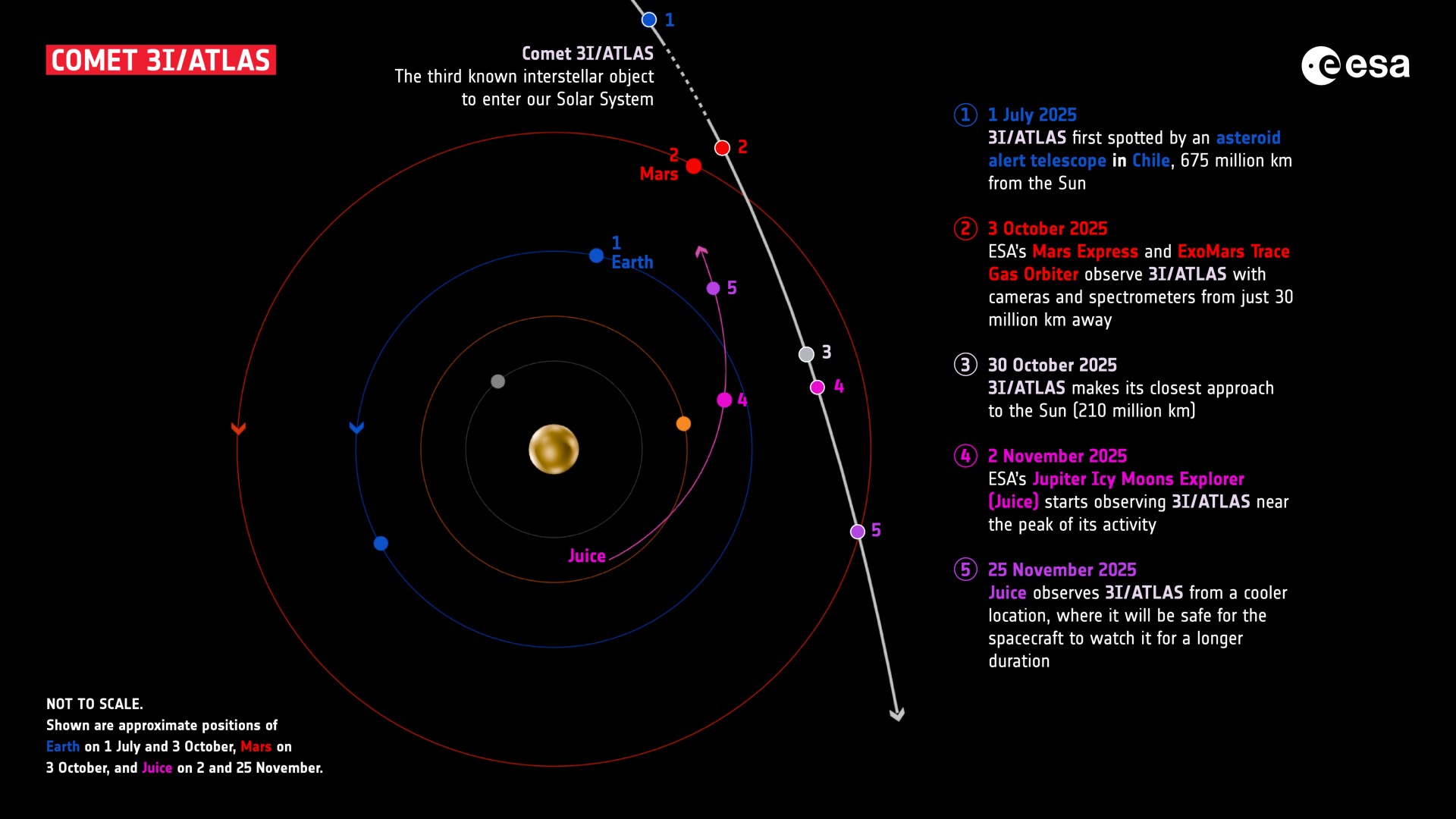

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is just a day away from perihelion, which is its closest point to the sun and the time around which it is expected to be most active. Although 3I/ATLAS is currently hidden from view from Earth, flying behind the sun, spacecraft elsewhere in the solar system still have the comet in their sights.

Perihelion for 3I/ATLAS takes place on Oct. 30, when the interstellar interloper will be 1.35 astronomical units (125 million miles, or 202 million kilometers) from the sun. (One astronomical unit is the average Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million km.)

Perihelion is the point in an object's orbit where it is closest to the sun. For comets on highly eccentric orbits, as opposed to planets on near-circular orbits, the effect of perihelion can be dramatic. As a comet nears the sun, the growing warmth causes ices on its surface to sublimate and it begins outgassing, growing a cloud called a coma around its nucleus. Comets voyaging near the sun also commonly sprout two tails — a dust tail and an ion tail made of charged particles stripped away from the comet by the solar wind. This activity makes the comet brighter and hence more noticeable, and at perihelion this outgassing, in theory, is at its most active.

As an interstellar object that is just passing through our solar system, 3I/ATLAS is not orbiting the sun. Nevertheless, its trajectory brings it closer to the sun and then farther away again, meaning it also has a perihelion approach.

Unfortunately, 3I/ATLAS moved into solar conjunction at the end of September. When this happened, it became lost in the sun's glare as it moved around the back of the sun, out of sight from Earth. It will not reappear in Earth's morning sky until later in November or the beginning of December, meaning that telescopes on Earth and in Earth orbit or at the L2 Lagrange point — a gravitationally stable spot on the other side of our planet from the sun — will miss out on seeing 3I/ATLAS at perihelion.

All is not lost, however, as we have a flotilla of spacecraft exploring the solar system that will have much better viewing angles than we get here on Earth. The small armada of spacecraft at Mars, for example, have a view of the hemisphere of the sun that 3I/ATLAS is currently rounding. In fact, our Mars missions had a ringside seat to 3I/ATLAS' closest approach to the Red Planet on Oct. 3, when it was 0.19 AU (17.6 million miles, or 28.4 million km) distant.

Other spacecraft that will be able to watch 3I/ATLAS at perihelion include NASA's Psyche mission to the asteroid of the same name and the Lucy mission to Jupiter's Trojan asteroids. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy moons Explorer (JUICE) probe, which recently conducted a flyby of Venus on its elongated journey to the Jovian system, will be closest as it heads in the general direction toward 3I/ATLAS. Unfortunately, because JUICE is currently using its primary antenna as a sun-shield to protect its instruments, it won't be able to transmit the data from its observations of 3I/ATLAS back to Earth until next February.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists are most interested in studying the chemistry of the comet at perihelion, because the gases and dust that come off the comet reveal its composition. Astronomers have already found that 3I/ATLAS contains more carbon dioxide than ordinary comets in the solar system, and a higher abundance of nickel. These differences reveal the chemistry of the molecular cloud of gas that spawned the comet and its home star system over seven billion years ago, allowing astronomers to make direct comparisons between the chemistry of the solar system and of the original home of 3I/ATLAS. At perihelion, more molecules could be revealed: So far, there has been a dearth of iron, but will iron emission from the comet pick up at perihelion?

When 3I/ATLAS does re-emerge from the sun at the back end of November, it could still be quite active — comets are unpredictable at the best of times — but, given its distance from Earth, it is expected to be quite faint, at a predicted magnitude 12. Astro-imagers and users of smart telescopes will be able to capture it, and it will of course be easy prey for the likes of the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.