Two Canadian ice caps have completely vanished from the Arctic, NASA imagery shows

Scientists gave the caps 5 years to live in a 2017 study. Climate change killed them in record time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

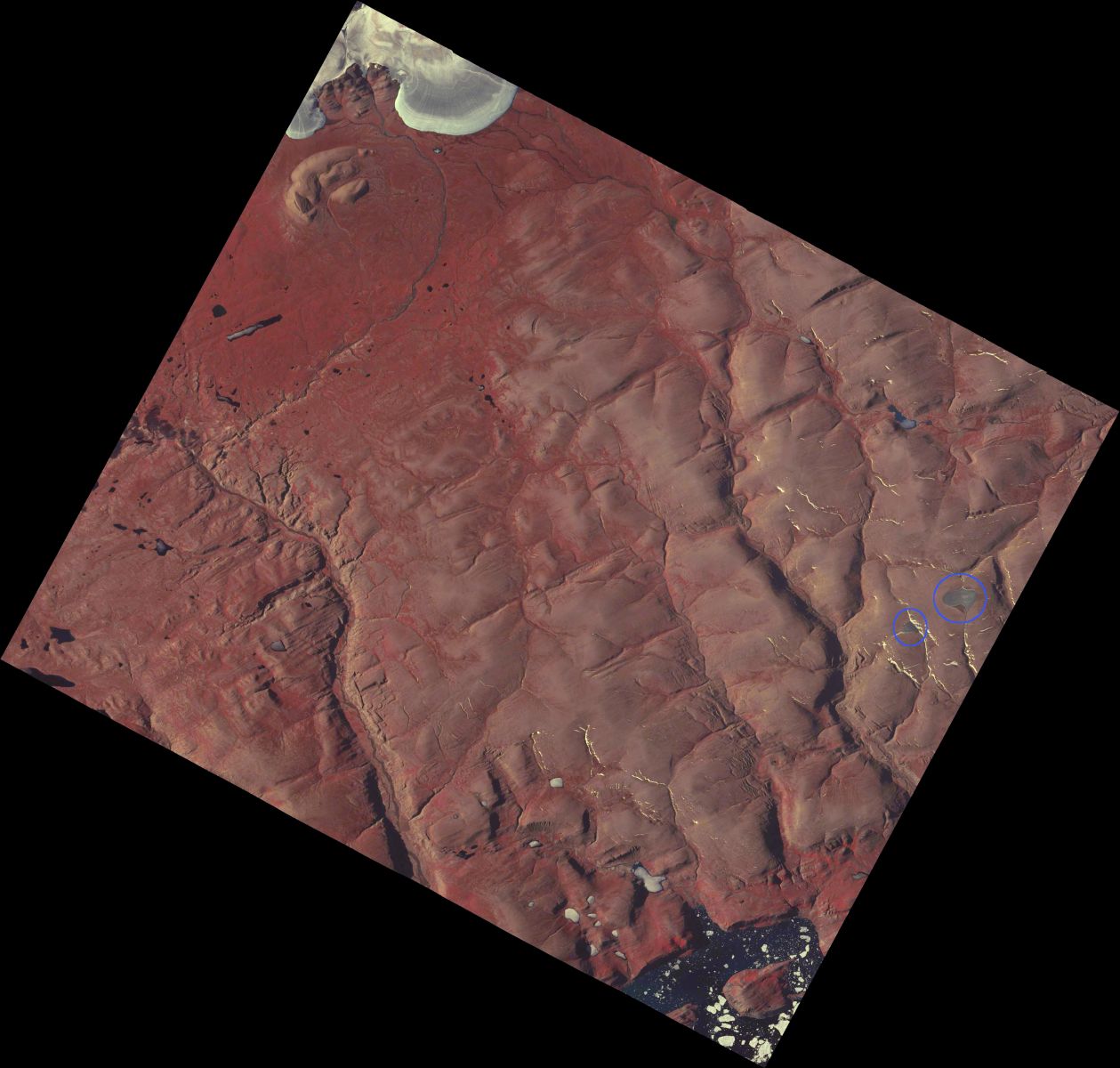

On frosty Ellesmere Island, where Arctic Canada butts up against the northwestern edge of Greenland, two once-enormous ice caps have completely vanished, new NASA imagery shows.

It's no mystery where the caps, known as the St. Patrick Bay ice caps, went. Like many glacial features in the Arctic — which is warming at roughly twice the rate of the rest of the world — the caps were killed by climate change. Still, glaciologists who have studied these and other ice formations for decades are unnerved by just how quickly the caps disappeared from our warming planet.

"When I first visited those ice caps, they seemed like such a permanent fixture of the landscape," Mark Serreze, director of National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Colorado, said in a statement. "To watch them die in less than 40 years just blows me away."

Related: Pink 'watermelon snow’ threatens major Italian glacier

Ice caps are a type of glacier that cover less than 19,300 square miles (50,000 square kilometers) of land on Earth, according to the NSIDC. These frosty domes typically originate at high altitudes in polar regions and blanket everything beneath them in ice (unlike ice fields, which can be interrupted or diverted by mountain peaks). The loss of Earth's ice caps not only contributes to sea-level rise, but also decreases the amount of reflective white surfaces on the planet, leading to more heat absorption, the NSIDC wrote.

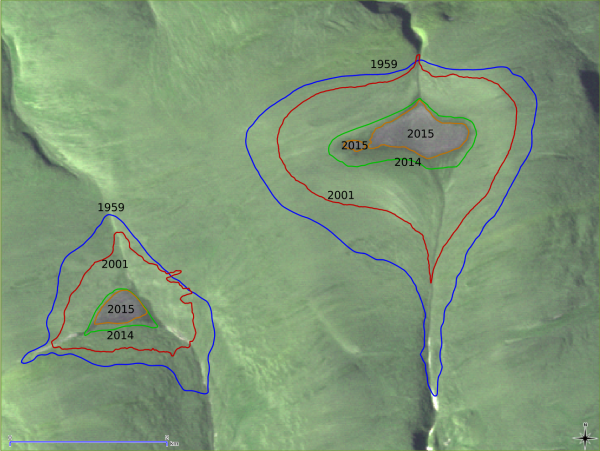

The St. Patrick Bay ice caps sat about 2,600 feet (800 meters) above Ellesmere Island's Hazen Plateau in Nunavut, Canada, where they existed for hundreds of years. Researchers aren't sure how large the caps were at their maximum extent, but when a team investigated in 1959 the caps covered about 3 square miles (7.5 square km) and 1.2 square miles (3 square km), respectively. (For comparison, the smaller one was about as big as Central Park in New York City.)

When researchers studied the caps again in 2017, the formations had shrunk to just 5% of their former sizes. Serreze, the lead author of the 2017 study, published in the journal The Cryosphere, predicted that the caps would vanish completely within five years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now here we are, two years ahead of schedule.

"We've long known that as climate change takes hold, the effects would be especially pronounced in the Arctic," Serreze said. "But the death of those two little caps that I once knew so well has made climate change very personal. All that's left are some photographs and a lot of memories."

The new satellite images, showing the Hazen Plateau's barren peaks, come from NASA's Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER), which imaged the island on July 14, 2020. Meanwhile, in nearby Greenland, ice loss has increased sixfold in the last 30 years. There's no question about it: Earth's climate is off the rails.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.