Does antimatter 'fall up'?

We need to talk about antimatter.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 1971, astronaut David Scott stood on the lunar surface, holding a hammer and a feather, and in the vacuum of the moon, he let them go. They struck the gray dust at the exact same time. It was a poetic nod to Galileo, who, centuries earlier, disproved the Aristotelian notion that heavy objects "want" to be on the ground more than light ones do.

This wasn't just a parlor trick for the cameras; it was a demonstration of the weak equivalence principle, which is the bedrock of general relativity. It states that all objects, regardless of their mass or internal composition, fall at the exact same rate in a gravitational field. When Einstein was building his masterpiece theory, he didn't try to explain why this happens. He simply assumed it was a fundamental rule and moved on.

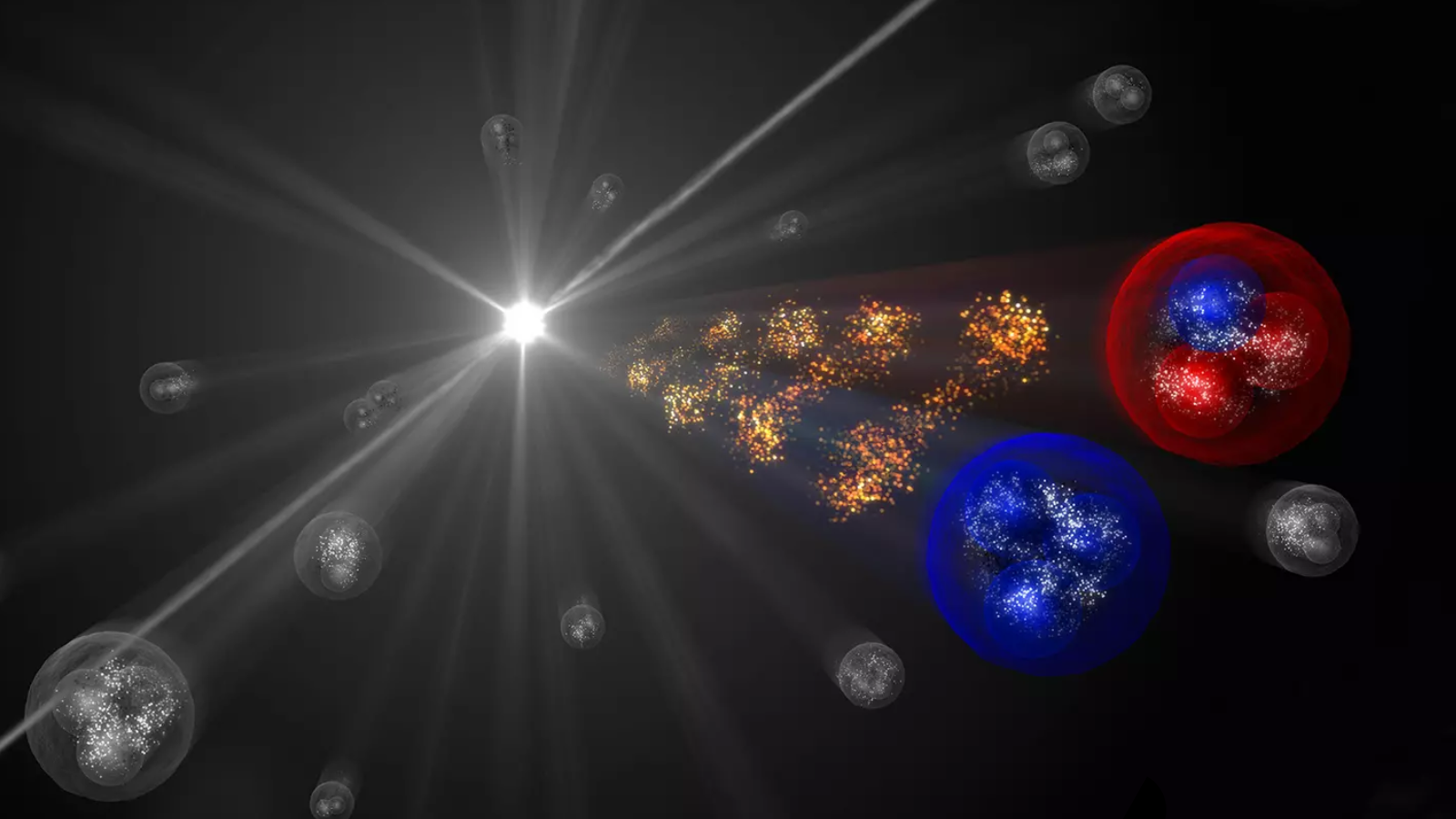

But what if there's an astrophysical creature that refuses to play by the rules? What if we dropped something so exotic, it wasn't even on Einstein's radar? We need to talk about antimatter.

To understand the allure of falling antimatter, we have to look at the history of its discovery. In the 1920s, physicist Paul Dirac was trying to force two very different worlds — quantum mechanics (the rules of the very small) and special relativity (the rules of the very fast) — to play together.

Dirac found an equation that worked, but it had a quirk. Just as the square root of 4 can be both 2 and -2, his equation offered two solutions for the energy of a particle: one positive and one negative. This was a problem. Positive energy has a "ground floor" at zero, but negative energy is a basement of a basement with no bottom.

Dirac's solution was what became known as the "Dirac sea." He imagined outer space not as an empty vacuum but as a filled "ocean" of negative energy states. If you kick one of these invisible particles into the positive realm, you leave behind a hole. That hole behaves like a normal particle but with an opposite charge. It was the first time a particle was predicted by pure math before being seen in a lab. We call it antimatter.

Why focus on antimatter to test gravity? Because antimatter is the bridge to the greatest divide in physics. General relativity (gravity) and quantum mechanics (everything else) famously do not get along. They speak different languages and live in different neighborhoods. Because antimatter is a pure product of the quantum world, it is the perfect candidate to test Einstein's theory of gravity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, this is a nightmare, for three reasons:

- When matter and antimatter touch, they annihilate in a flash of pure energy.

- Nature doesn't just hand us antimatter; we have to build it in advanced laboratories.

- Compared with the electromagnetic force, gravity is incredibly weak.

To overcome these hurdles, scientists at CERN's ALPHA-g experiment had to get creative. First, they made neutral antihydrogen by pairing antiprotons with positrons (anti-electrons). Because these antiatoms are neutral, they aren't pushed around by electricity.

The team caught about a hundred of these antiatoms in a Penning trap, which is a magnetic bottle that holds them in place because, while neutral, they still act like tiny bar magnets. Then, using lasers, the researchers chilled the atoms to near absolute zero to stop them from jiggling.

Then came the moment of truth: They slowly turned down the magnetic field.

If antimatter ignored the weak equivalence principle, the atoms might have drifted upward, repelled by Earth. If Einstein was right, they should tumble downward. The researchers waited for the flash of annihilation as the antiatoms escaped the trap and hit the walls of the container. After they filtered out the noise of stray cosmic rays, the results were clear: Roughly 80% of the antiatoms fell through the bottom of the trap.

Antimatter falls down. It's an anti-climactic (ha ha) result in the best way possible. It means the weak equivalence principle holds firm and Einstein's vision of a universal gravitational response remains unblemished.

However, the case isn't entirely closed. While we know antimatter falls down, we don't yet know if it falls at the exact same acceleration as regular matter does. If there is even a 1% difference in the speed of the fall, it would signal a total revolution in physics — a sign that gravity treats mirror matter differently. But for now, the universe remains a place where hammers, feathers and antihydrogen all race to the floor at the same speed.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.