Special relativity explained: Einstein's mind-bending theory of space, time and light

Discover how Einstein’s theory of special relativity reshaped physics by linking space, time, mass, and energy in a universe governed by the speed of light.

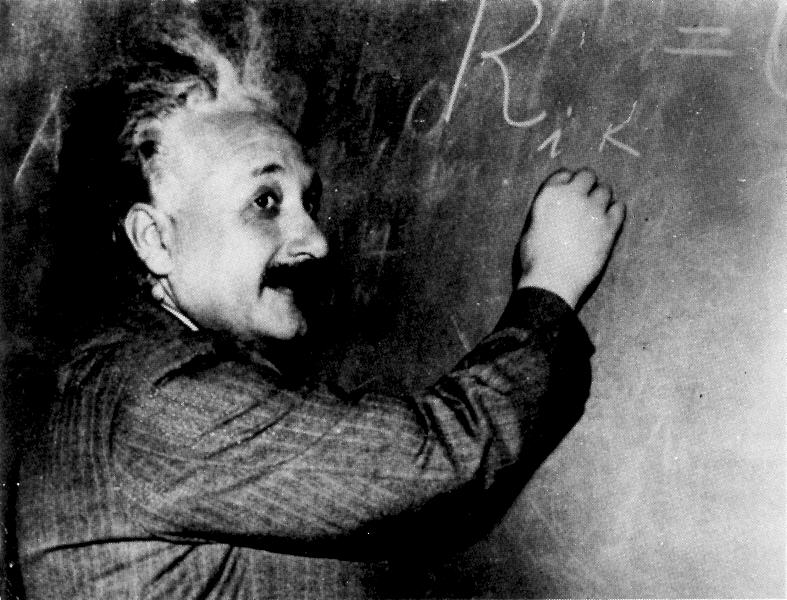

Albert Einstein's 1905 theory of special relativity revolutionized modern physics.

This groundbreaking theory explains how speed affects mass, time, and space, and introduced the world to the most famous equation in science: E = mc².

Special relativity applies to situations involving high speeds, massive energy, and vast distances — all in the absence of gravity. For gravity, Einstein expanded on this work a decade later with his 1915 theory of general relativity.

Key concepts of special relativity

Why can't anything travel faster than light?

As objects approach the speed of light (approximately 186,282 miles per second or 300,000 km/s), their mass effectively becomes infinite, requiring infinite energy to move. This creates a universal speed limit — nothing with mass can travel faster than light.

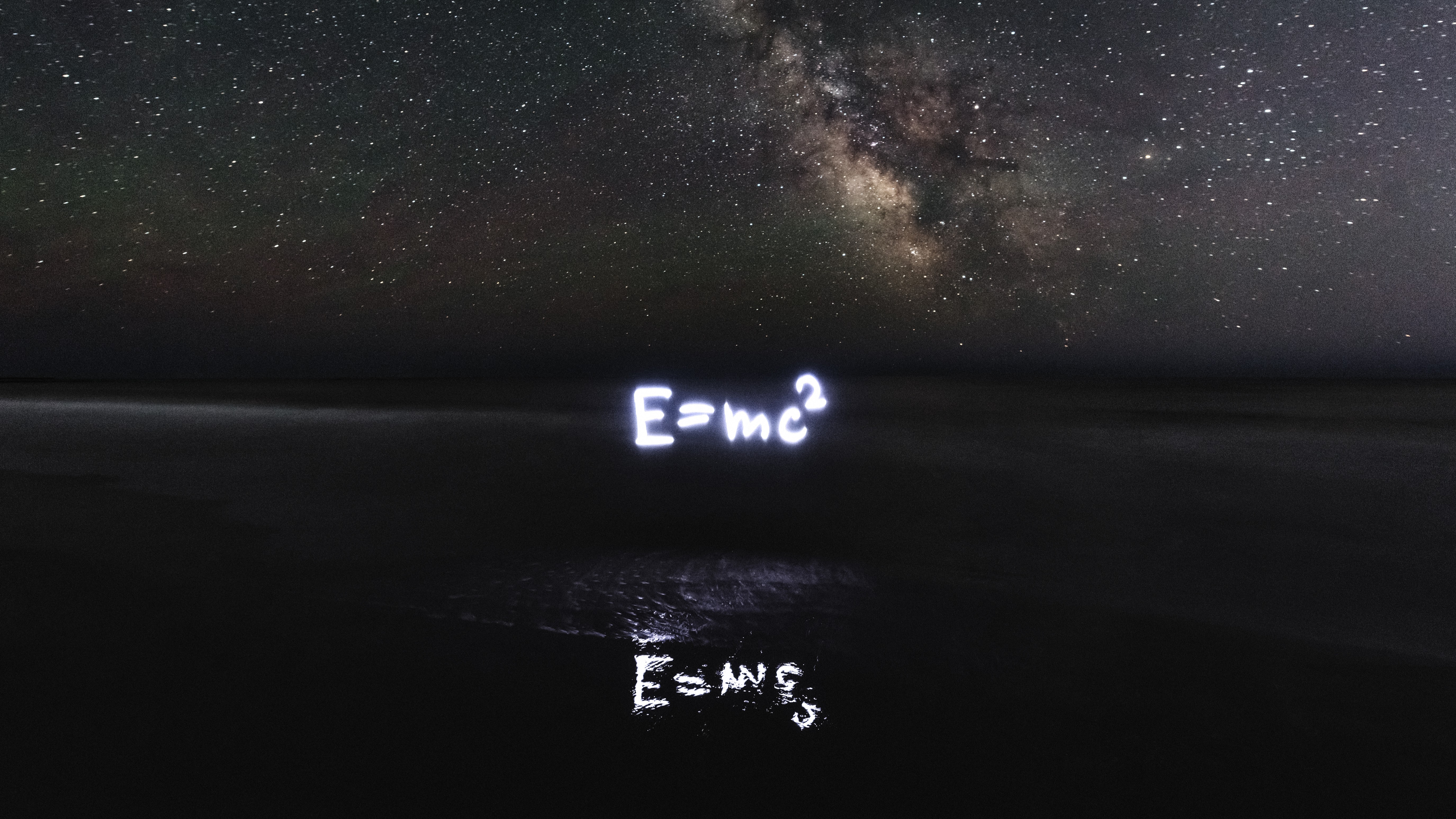

What does E = mc² mean?

Einstein’s equation, E = mc², means that energy (E) and mass (m) are interchangeable. The speed of light (c) squared is an enormous multiplier, so even a tiny bit of mass contains an enormous amount of energy.

For example, converting the atoms in a paper clip into pure energy would release the equivalent of 18 kilotons of TNT.

Before Einstein: Newton and the luminiferous ether

Before Einstein, Isaac Newton’s three laws of motion formed the bedrock of classical physics. But they couldn't explain everything, especially the behavior of light.

To fit light into Newtonian physics, scientists proposed the luminiferous ether, a hypothetical medium for light waves. However, the 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment showed that light’s speed is constant, regardless of Earth's motion, suggesting the ether didn't exist.

Physics needed a new framework. Enter Einstein.

How did Einstein develop special relativity?

According to Einstein, in his 1949 book "Autobiographical Notes" (Open Court, 1999, Centennial Edition), Einstein described imagining himself as a teenager chasing a beam of light. If he could catch up, he reasoned, he’d see the wave standing still. But that contradicted James Clerk Maxwell, whose equations required that electromagnetic waves always move at the same speed in a vacuum: 186,282 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This contradiction led Einstein to propose that the laws of physics — and the speed of light — are the same for all observers, no matter their motion. This idea formed the basis of special relativity.

Why time is relative

What is time dilation?

One of the many implications of Einstein's special relativity work is that time moves relative to the observer. An object in motion experiences time dilation, meaning that when an object is moving very fast it experiences time more slowly than when it is at rest.

For example, when astronaut Scott Kelly spent nearly a year aboard the International Space Station starting in 2015, he was moving much faster than his twin brother, astronaut Mark Kelly, who spent the year on the planet's surface. Due to time dilation, Mark Kelly aged just a little faster than Scott — "five milliseconds," according to the earth-bound twin. Since Scott wasn't moving near lightspeed, the actual difference in aging due to time dilation was negligible. In fact, considering how much stress and radiation the airborne twin experienced aboard the ISS, some would argue Scott Kelly increased his rate of aging.

But at speeds approaching the speed of light, the effects of time dilation could be much more apparent. Imagine a 15-year-old leaves her high school traveling at 99.5% of the speed of light for five years (from the teenage astronaut's perspective). When the 15-year-old got back to Earth, she would have aged those 5 years she spent traveling. Her classmates, however, would be 65 years old — 50 years would have passed on the much slower-moving planet.

We don't currently have the technology to travel anywhere near that speed. But with the precision of modern technology, time dilation does actually affect human engineering.

Special relativity in everyday technology

Despite sounding abstract, special relativity affects modern life, particularly in GPS satellites.

GPS devices work by calculating a position based on communication with at least three satellites in distant Earth orbits. Those satellites have to keep track of incredibly precise time in order to pinpoint a location on the planet, so they work based on atomic clocks. But because those atomic clocks are on board satellites that are constantly whizzing through space at 8,700 mph (14,000 km/h), special relativity means that they tick an extra 7 microseconds, or 7 millionths of a second, each day, according to American Physical Society publication Physics Central. In order to maintain pace with Earth's clocks, atomic clocks on GPS satellites need to subtract 7 microseconds each day.

With additional effects from general relativity (Einstein's follow-up to special relativity that incorporates gravity), clocks closer to the center of a large gravitational mass like Earth tick more slowly than those farther away. That effect adds microseconds to each day on a GPS atomic clock, so in the end engineers subtract 7 microseconds and add 45 more back on. GPS clocks don't tick over to the next day until they have run a total of 38 microseconds longer than comparable clocks on Earth.

Special relativity vs quantum mechanics

While special relativity governs massive objects and high speeds, quantum mechanics rules the tiny and unpredictable world of subatomic particles. One is smooth and continuous; the other is discrete and probabilistic.

Physicists have developed relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory to merge the two. But the holy grail remains: a unified theory that combines quantum mechanics with general relativity.

Frequently asked questions

What's the difference between special and general relativity?

Special relativity deals with space, time, and energy at constant motion — no gravity involved. General relativity extends these ideas to include gravity and acceleration.

What does "relativity" mean in special relativity?

It means that measurements of time and space depend on the observer's relative motion.

Why is the speed of light constant?

Einstein showed that no matter how fast you're moving, you will always measure light traveling at the same speed. This constancy is key to understanding why time and space shift for moving observers.

Additional resources

- Check out this time dilation calculator from Omni Calculator.

- Explore Einstein's thought experiments in this video from PBS Nova.

- Go back to the source and read Einstein's explainer in this translated edition of his book, Relativity: The Special and General Theory (Dover, 2001).

Vicky Stein is a science writer based in California. She has a bachelor's degree in ecology and evolutionary biology from Dartmouth College and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz (2018). Afterwards, she worked as a news assistant for PBS NewsHour, and now works as a freelancer covering anything from asteroids to zebras. Follow her most recent work (and most recent pictures of nudibranchs) on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.