Exoplanets that cling too tightly to their stars trigger their own doom: 'This is a completely new phenomenon'

"The planet seems to be triggering particularly energetic flares."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Some planets take the expression "you're your own worst enemy" to the extreme. At least, that's what astronomers found when they recently discovered a doomed planet clinging to its parent star so tightly that it's triggering explosive outbursts and destroying itself.

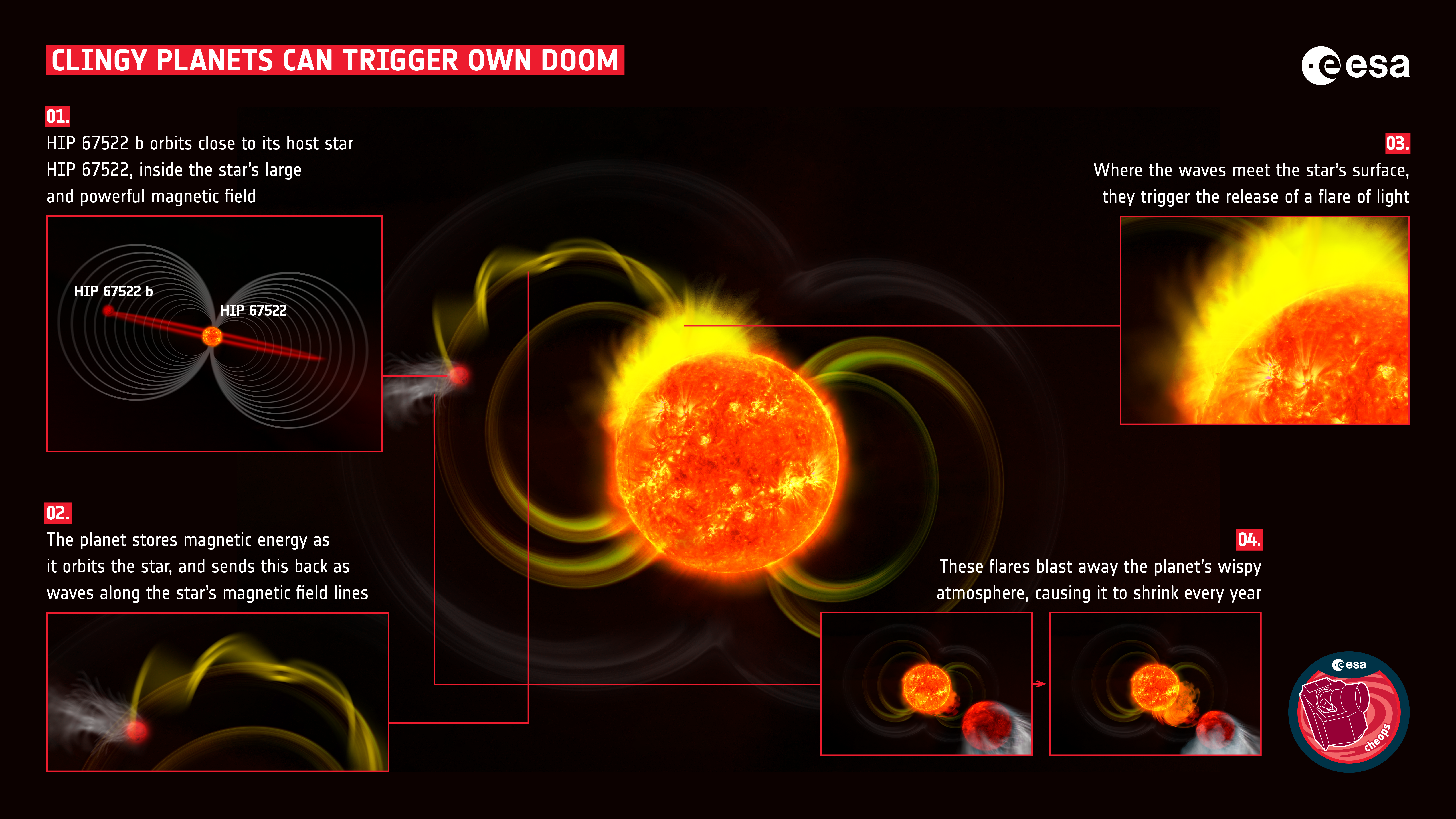

The clingy, self-destructive extrasolar planet, or "exoplanet," in question is called HIP 67522 b. It orbits a young, 17 million-year-old star so closely that one of its years lasts just one Earth week.

Considering our middle-aged star, the sun, is 4.6 billion years old, the stellar parent of this clingy exoplanet (called HIP 67522) is a relative infant. This means it is bursting with energy.

Since the mid-1990s, when the first exoplanets were discovered, astronomers have pondered whether exoplanets can orbit their stars closely enough that stellar magnetic fields are impacted. Over 5,000 exoplanet discoveries later and astronomers still hadn't found the answer.

That is, until now.

"We hadn't seen any systems like HIP 67522 before; when the planet was found, it was the youngest planet known to be orbiting its host star in less than 10 days," team leader and Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) researcher Ekaterina Ilin said in a statement. "I have a million questions because this is a completely new phenomenon, so the details are still not clear."

Kid planet triggers stellar parent

The team discovered HIP 67522 while using NASA's exoplanet hunting spacecraft TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) to survey flaring stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

TESS discovered some interesting characteristics of HIP 67522, prompting a follow-up investigation with the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Cheops (Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite).

"We quickly requested observing time with Cheops, which can target individual stars on demand, ultra precisely," Ilin said. "With Cheops, we saw more flares, taking the total count to 15, almost all coming in our direction as the planet transited in front of the star as seen from Earth."

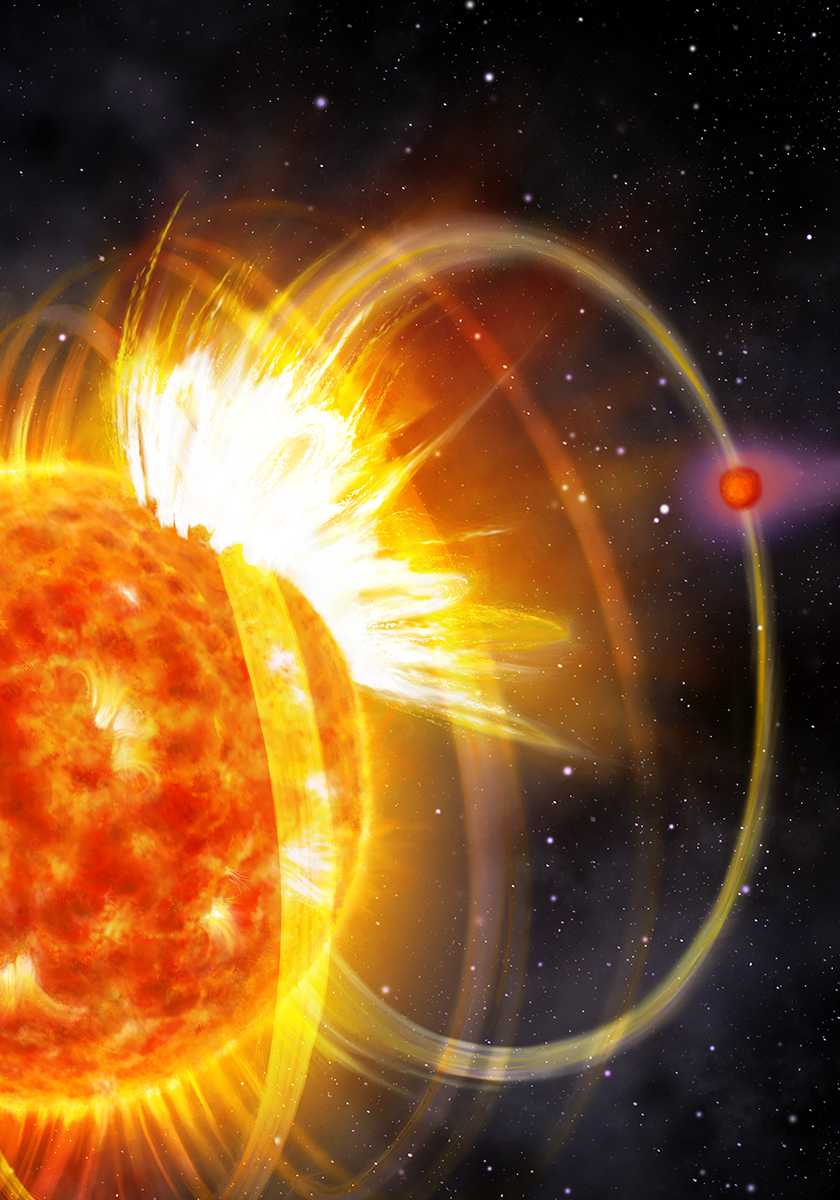

Ilin and colleagues discovered that the stellar flares being thrown out by HIP 67522 occur when its clingy planet passes in front of, or "transits," the star. That means these flares are very likely triggered by the planet itself. The team theorizes this occurs because HIP 67522 b is so close to its star that it exerts a magnetic influence on the star.

As the planet whips around the star, it gathers energy, which is redirected as waves rippling down the star's magnetic field lines. When a wave hits the stellar surface, a massive flare is triggered.

"The planet seems to be triggering particularly energetic flares," Ilin explained. "The waves it sends along the star’s magnetic field lines kick off flares at specific moments. But the energy of the flares is much higher than the energy of the waves.

"We think that the waves are setting off explosions that are waiting to happen."

This is therefore the first hard evidence that planets can influence the behavior of their stars.

HIP 67522 b isn't just triggering flares facing nowhere, though. These induced flares are directed toward the world itself. In particular, it is bombarded with around six times the radiation a planet at this orbital distance usually would experience.

As you might imagine, this bombardment spells doom for HIP 67522 b. The planet is currently around the size of Jupiter, but it has around the density of candy floss.

The planet's wispy outer layers are being stripped away by harsh radiation, causing the planet to lose even the little mass it has. Over the next 100 million years, HIP 67522 b is expected to drop from the size of Jupiter to around the size of Neptune. The team doesn't actually quite know how extreme the damage these self-inflicted flares could be for HIP 67522 b.

"There are two things that I think are most important to do now. The first is to follow up in different wavelengths to find out what kind of energy is being released in these flares — for example, ultraviolet and X-rays are especially bad news for the exoplanet," Ilin said. "The second is to find and study other similar star-planet systems; by moving from a single case to a group of 10 to 100 systems, theoretical astronomers will have something to work with."

The team's research was published on Wednesday (July 2) in the journal Nature.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.