No, Particle Accelerators Will Not Destroy the Planet, But Humans Might

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The future could be glorious or grim, and the gust of wind that tips things one way or another is us — the humans of the 21st century.

"The stakes are very high this century," said British cosmologist Martin Rees. "It's the first century when human beings … can determine the planet's future." [10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life]

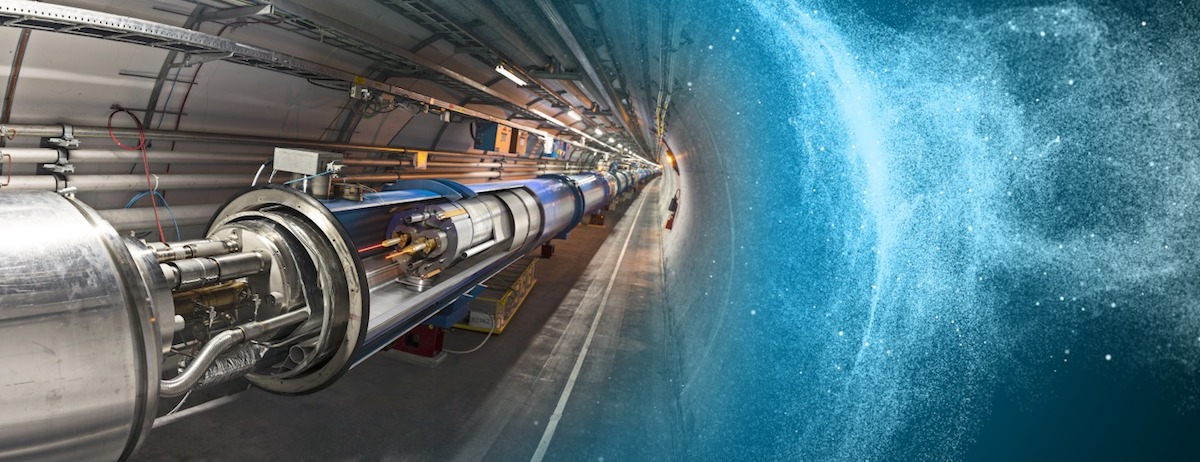

For the past couple of days, news outlets have been reporting that Rees' new book "On the Future: Prospects for Humanity" (Princeton University Press, 2018) makes a rather spectacular claim: If things go wrong, particle accelerators that slam subatomic particles together at immense speeds — like the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, Switzerland,— could turn Earth into a dense sphere or black hole.

In fact, Rees told Live Science in a recent interview, his book claims the opposite: The probability of this happening is very, very low. The idea of the LHC forming mini-black holes has been circulating for a while and is not something to worry about, he said.

"I think people quite rightly thought about this question before they did the experiments, but they were reassured," he said. The reassurance mainly comes from the fact that nature already performs such experiments — to an extreme.

Cosmic rays, or particles with much higher energies than those created in particle accelerators, frequently collide in the galaxy, and haven't yet done anything disastrous like rip space apart, Rees said.

"It's not stupid to think about these things, but on the other hand, they're not serious worries," he said. But in contrast, "if you're doing something where you have no guidance from nature, then you’ve got to be a bit careful."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's in these cases that technology can be a realistic threat for the future, he said.

When nature doesn't know the answer

Gene editing, for example, can yield new organic products that don't exist in nature, Rees said.

Sometimes, if "you tinker with a virus, then of course you can't be quite sure what the consequences are," he said. "It may well be that you can create a form of a virus which has not arisen through natural mutations."

There's much conversation around gene drives, for example — modifications that are being considered for mosquitoes to reduce disease transmission. Gene drives essentially tweak the genetic code to alter the likelihood of inheriting certain traits, and can lead to "unpredictable environmental effects," he said.

Technology is also making it easier for one person's actions to have far-reaching consequences, he said.

"Just a few people anywhere in the world can cause something which has global consequences in a way they couldn’t [before]," Rees said. One example is a cyberattack.

Technology also does incredible things, especially in medicine and space travel. And as such, "things can go extremely well," Rees said. "But there are all these hazards along the way because of misuse of technologies."

The second major threat to the future is our collective influence on the climate, environment and biodiversity, he said. So, it's important to have international conversations about how to combat the pressures humanity has placed on the world, he added. And it's much easier to solve the world's problems, such as by combating climate change, than by packing up our things and going to a new planet, he said.

"It’s a dangerous illusion to think that we can escape the world's problems by going to Mars," Rees said. In fact, robots — who will likely be better-adapted to space travel than humans — will mostly be the ones exploring the cosmos. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

Rees doesn't think robots are truly a threat for the future.

"I don't worry as much as some people do about AI taking over," Rees said. Humans evolved from earlier primates because of natural selection, and the traits that were favored were intelligence and aggression, he said. Electronics "are not engaged in a struggle for survival as in Darwinian selection, so there's no reason why they should be aggressive," he said.

For that reason, they probably won't kill off the human race and expand into the universe. That would be too "anthropomorphic" of them, he said. "They might just want to sit and think," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.