Project Mercury: America's 1st crewed space program

Project Mercury was NASA's program that launched the first American astronauts into space, completing a total of six crewed spaceflights.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Project Mercury was NASA's inaugural human spaceflight program.

The program had two aims: to see if humans could function effectively in space, and to put a man in space before the Soviet Union did. While Project Mercury failed in the second aim, it did provide the technological basis for more challenging missions in the Gemini and Apollo programs. It also turned the seven original astronauts into superstars.

Program origins

In the late 1950s, the United States was worried about the Soviet Union's supremacy in space exploration. The Soviet Union unexpectedly sent Sputnik, the first satellite into space, on Oct. 4, 1957. The U.S. Congress urged action immediately to deal with the problem, with some politicians saying the Soviet coup might be a threat to national security.

There were some calls to create a military astronaut space program, building on the high-altitude flights that test pilots were already conducting. President Dwight Eisenhower initially agreed, but upon speaking with some advisors, he ultimately backed a proposal for a non-military space agency called NASA that would send the first astronauts into space. NASA was formed in 1958 from the former National Advisory Committee on Astronautics (NACA), and several other centers.

In 1959, the new agency selected seven astronauts from a pool of military test pilots to simplify the astronaut selection procedure, according to NASA. The first astronauts had to meet several stringent requirements: be under 40 years old; be less than 5 feet, 11 inches tall; be in excellent physical condition; have extensive engineering experience; be a test pilot school graduate; and have a minimum of 1,500 hours of flying time. Since most military test pilots were white males at the time, this meant that the first astronauts were also of that demographic group.

NASA screened 500 records and decided that an initial group of 110 men were qualified. These men were divided equally and arbitrarily into three groups, which would receive a confidential briefing advising them of the opportunity to fly into space. However, because so many men from the first two groups agreed to participate in the astronaut program if chosen, the third group of military personnel was never called upon.

From there, the semi-finalists underwent extensive psychological and physical testing to winnow down the field. The selected seven astronauts were announced to the world on April 9, 1959. They and their families instantly became worldwide celebrities. Their fame was further enhanced with an exclusive contract with Life magazine for $500,000 (or about $4.3 million today). The stories painted the astronauts as American heroes fighting communism with their space missions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Early Mercury flights

While the human Mercury program received most of the attention, the first living creature to fly on Mercury was not a test pilot, but a chimpanzee.

The chimp, named Ham (an acronym for Holloman Aerospace Medical Center), blasted off aboard a Mercury Redstone rocket on Jan. 31, 1961. NASA officials wanted to fly Ham first in case the flight ran into technical problems, which it did. The spacecraft flew higher and faster than anticipated and splashed down more than 400 miles off course. However, Ham emerged healthy except for mild dehydration and fatigue.

After an uncrewed Mercury test flight on March 24, NASA felt ready to bring its first astronaut into space. The agency selected Alan Shepard, a World War II veteran and Navy test pilot. However, the Soviets beat the Americans once again, sending Yuri Gagarin into space on April 12. Three weeks later, on May 5, Shepard lifted off for a 15-minute suborbital flight.

Shepard's Freedom 7 flight was a success, but he was frustrated at not making it first. "We had 'em," Shepard is reported to have said about the Soviets at the time, according to the Neal Thompson 2007 biography, "Light This Candle: The Life and Times of Alan Shepard." "We had 'em by the short hairs, and we gave it away."

Mercury's next flight, on July 21, 1961, ran into a major snag. Gus Grissom's Liberty Bell 7 performed relatively well on the 15-minute suborbital hop until splashdown when the door unexpectedly blew open. Grissom found himself in the water as the recovery helicopter tried in vain to rescue the spacecraft. The cause of the door problem was never found.

In the aftermath of the debacle, some people argued that Grissom had messed up. However, a 2016 book by George Leopold, "Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom," argues that the astronaut displayed quick thinking while in the water, including trying to rescue the spacecraft at the peril of his own life, according to Ars Technica. Grissom recovered from the incident and was assigned to the Apollo 1 mission, but he and his crew members died on the launch pad on Jan. 27, 1967, during a fire.

Reaching orbit

While the Mercury missions were technological feats for NASA and its contractors, they were quite short — only 15-minute arcs between Florida and the Atlantic Ocean. The Soviets, meanwhile, had already done orbital missions that circled the Earth several times — including Gagarin's historic first human spaceflight. Getting the Americans to orbit would require a more powerful rocket, among other mission changes.

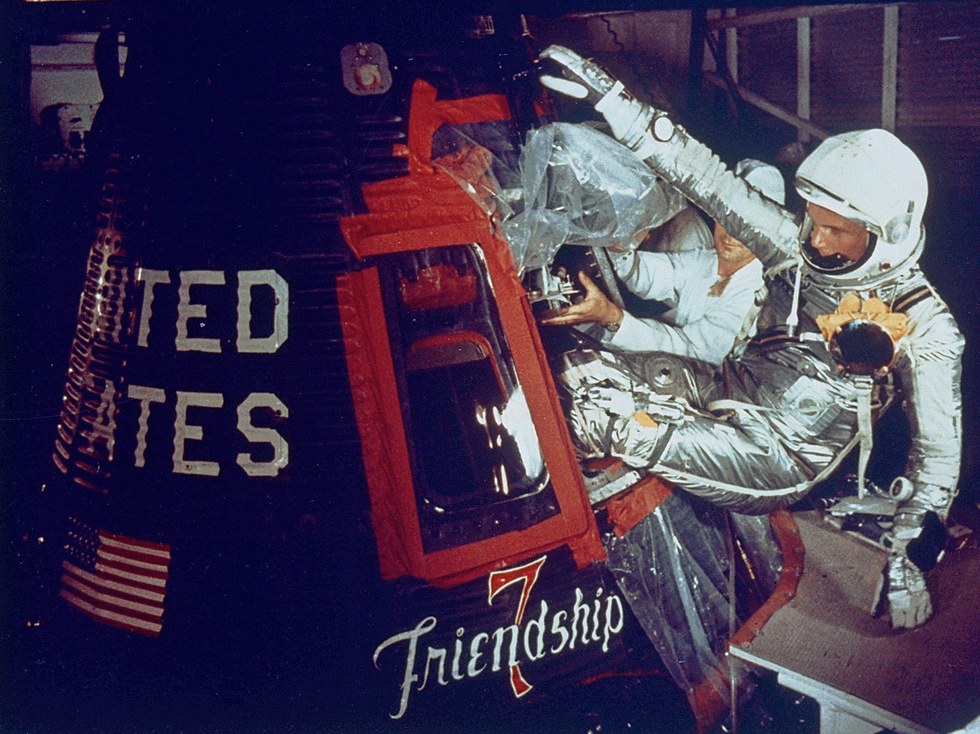

So when John Glenn blasted off to circle Earth three times, his Friendship 7 spacecraft did it aboard a more powerful Mercury-Atlas rocket combination. Glenn's Feb. 20, 1962, mission was another checkout of the spacecraft, and how a human would react to several hours in space. During his five-hour mission, he also saw strange "fireflies" that were appearing to follow his spacecraft, a phenomenon later explained as ice crystals coming off the hull.

Controllers on the ground saw an indication that his landing bag had prematurely deployed. They waited to tell Glenn, then close to re-entry instructed Glenn to keep his retrorocket package strapped onto his spacecraft as a precaution. The indication turned out to be false, and Glenn was upset that he had not been told as soon as the problem arose. Glenn became a public hero following his flight; he wanted to return to space, but then-U.S. president John F. Kennedy (among others) considered him too valuable, according to the New York Times. (Glenn eventually became a senator for Ohio, then returned to space at age 77 aboard shuttle mission STS-95 in 1998.)

The next Mercury mission, Aurora 7, again ran into splashdown problems on May 24, 1962. Pilot Scott Carpenter landed about 250 miles (400 kilometers) off course after about five hours in space. Some space program officials, notably flight director Chris Kraft, blamed the problem on Carpenter's inattention during the mission.

In two oral interviews with NASA, Carpenter said it was a combination of technical problems (some sensors were malfunctioning) and excessive fuel use as Carpenter worked to solve Glenn's firefly mystery.

"There was excessive fuel use, which scared a lot of the folks on the ground," Carpenter recalled in 1998. "There was enough. There was enough for the entry. A lot of people thought there would not be. And it was anybody's guess."

Carpenter never flew again.

Closing the program

NASA was already planning for the next space program — Gemini, which would test orbital maneuvers and spacewalks in preparation for eventual moon missions during Apollo. With the two-man Gemini spacecraft heavily in development, NASA focused the last two Mercury missions on making sure that spacecraft and astronauts could be ready for missions that lasted over several days. Wally Schirra named his spacecraft Sigma 7 to honor excellence in engineering. He launched on Oct. 3, 1962, for a six-orbit mission, carefully rationing his fuel through the mission by using just small bursts of thruster fuel at a time.

By the time he was ready to go back to Earth, more than half of Schirra's fuel was left. In his autobiography "Schirra's Space," the astronaut said he had to dump the remainder. His mission drew praise in NASA; Schirra also flew on Gemini 6 and Apollo 7, becoming the only astronaut to fly in all three of NASA's manned space programs.

Schirra's success cleared the way for the final flight, Faith 7. Gordon Cooper flew successfully for 22 orbits between May 15 and 16, 1963.

Notably, Deke Slayton, an astronaut who was part of the original seven astronauts selected for Mercury, never flew during the program. He was sidelined due to a heart condition. He eventually made it into space during the July 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project spaceflight between the United States and the Soviet Union.

While Mercury is not always well-remembered in space history, it was the foundation for all space missions in the American program. Mercury's surviving astronauts continued to popularize space even after leaving NASA, including writing autobiographies and making public appearances. Its last living astronaut, John Glenn, died of natural causes in December 2016, at age 95.

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.