The Greatest Mysteries of Jupiter's Moons

Each week this summer, Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site of SPACE.com, presents The Greatest Mysteries of the Cosmos, starting with the coolest stuff in our solar system.

The biggest planet in the solar system, Jupiter, also boasts the most moons, with 64 currently catalogued. Most of these moons are tiny, lumpy rocks — apparently asteroids captured by Jupiter's gravity — and they swarm about the giant planet like so many bees around a hive.

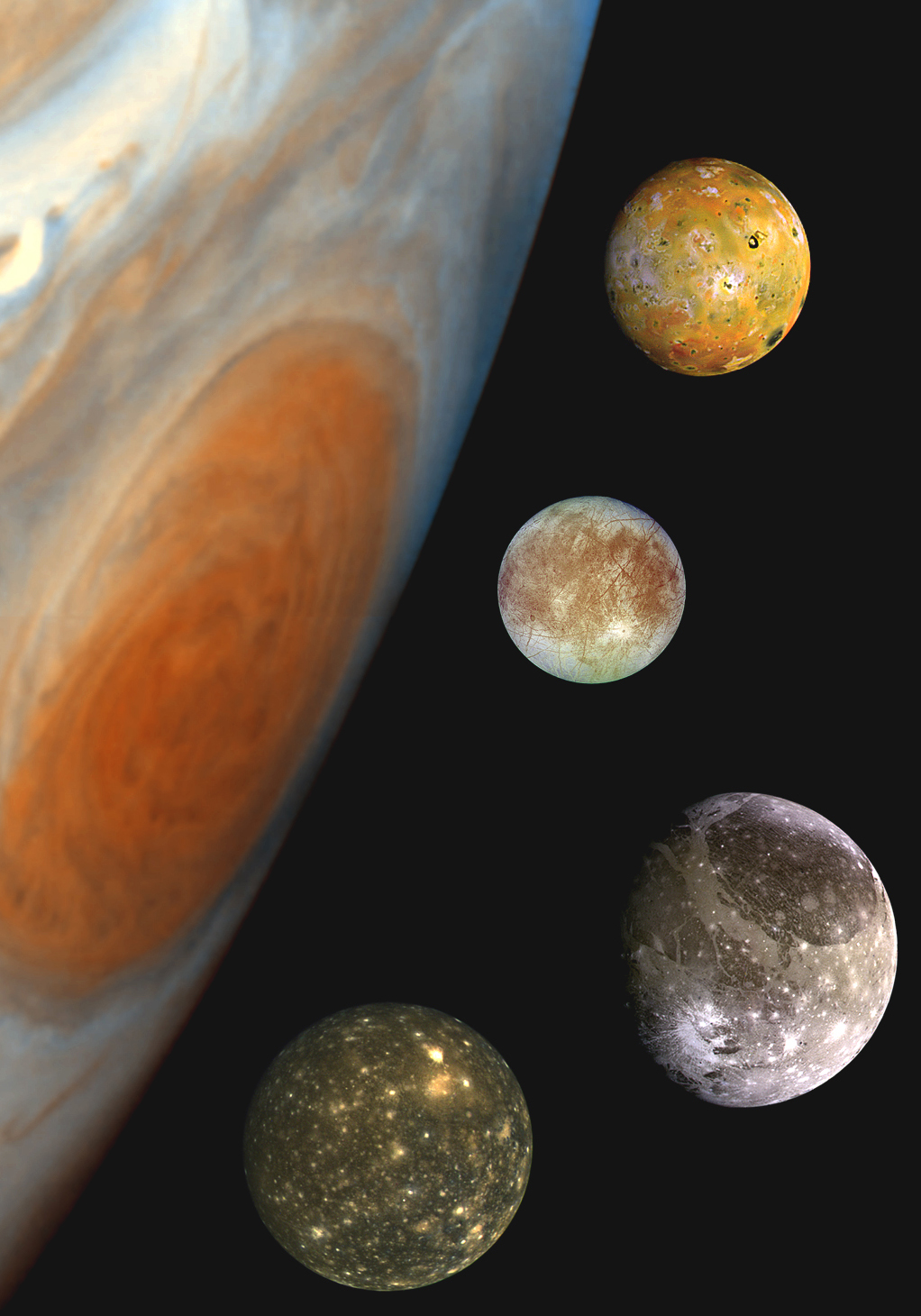

Four of Jupiter's moons, however, are quite substantial — so much so that they can be seen through a rudimentary telescope. The inventor of just that instrument, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, first saw the thusly named "Galilean moons" in 1610: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Together, these four moons comprise more than 99.9 percent of the mass of Jupiter's satellites. Each of them has a distinctive character, and they all present vexing scientific puzzles. Here is a rundown of the top mysteries regarding Jupiter's primary four moons. [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

Io, the hyperactive pizza moon

Io is the closest of the Galilean moons to Jupiter. This proximity is thought to help explain the moon's uniquely hellish, sulfur-yellow, red-splotched and pockmarked appearance.

Those pocks, in fact, are volcanoes. Io sports 400 or so active volcanoes, as well as soaring mountains formed by tectonics. Overall, the moon is the most geologically active object in our solar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The energy powering this activity comes largely from a gravitational tug-of-war between Jupiter and the other three Galilean moons with Io caught in the middle. The constant stretching and compressing that this tug exerts on Io heats its interior, prompting the moon to often ooze out lava and spew sulfur and ash into space.

Such tidal forces, however, might not account for all this oomph. The history of variances in the gravitational flexing of Io also remains murky.

"I don’t think we know enough about the exact frequency of these things to adequately assess the whole mechanism," said Scott Bolton, principal investigator for NASA's Juno spacecraft mission, which launches Friday (Aug. 5) to study Jupiter.

Given how interesting the moon is, "Io could be the focus of an entire mission," added Bolton, who, in addition to his Juno post, is also director of the space science and engineering division at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

Europa, a smart bet for extraterrestrial life?

The moon of Jupiter that's definitely highest on the list for someday getting its own dedicated mission is Europa. This icy-white object with brownish streaks on its surface stands as one of the best candidates for hosting extraterrestrial life in our solar system.

Under an icy crust anywhere from a couple to perhaps 20 miles (three to 32 kilometers) thick, Europa probably harbors a saltwater ocean. Depending on the assumptions and models used, this ocean could have twice the volume of all those on Earth. [Why Doesn't Our Moon Have a Name?]

Understandably, astronomers are bubbling over with questions about this subterranean (sub-Europian?) sea. The chief query: "Might it allow for life development in any way?" asked Bolton.

The idea is not so far-fetched. Tidal flexing from Jupiter could keep the interior of Europa warm. This energy could, in turn, support microbial life analogous to that found around hydrothermal vents in Earth's oceans. Cosmic rays from space striking the crustal ice could even free up oxygen to power bigger life forms, such as fish.

Ganymede, big and oddly magnetic

Jupiter's largest moon, Ganymede, reigns as the biggest moon in the solar system. In fact, it's even larger than the planet Mercury.

Another distinction for Ganymede: it's the only moon with its own magnetosphere, which is a region surrounding the world where charged particles from the sun are deflected by a magnetic field.

"How that [magnetosphere] gets created is very fascinating," said Bolton. "We don’t know of another small body that has that."

Ganymede's magnetosphere is most likely made in a manner much like Earth's, due to convection in the moon's liquid iron core. Learning how it's generated would help with better understanding our own planet's magnetic field.

To boot, Ganymede might also a hidden ocean sloshing under its gray, rocky and icy crust.

Battered Callisto

The Galilean moon with the farthest orbit from Jupiter is Callisto. Unlike Io and Europa (and even Ganymede to an extent), where geologic activity has erased many craters, Callisto bears the scars of eons' worth of meteorite impacts. The geologically dead moon is considered the most heavily cratered object in the solar system.

Callisto's landscape is therefore among the oldest on record, aged some four billion years. Analyzing its surface materials would be like opening a time warp back to the early solar system.

Callisto might be full of surprises on the inside, too — an underground ocean could lurk here as well, yet another possible abode for alien life out in Jupiter's neighborhood.

Bonus boggler: Ringed remnants of a destroyed moon

Since its discovery in 2000, a tiny moon just 2.5 miles (four kilometers) in diameter and given the designation S/2000 J 11 has gone missing. Astronomers think the moonlet has actually smashed into Himalia, Jupiter's fifth most massive moon after the four Galileans.

That possible impact appears to have created a streak of material, observed in 2006, that might even be a whole new ring around Jupiter. The planet's faint rings naturally do not get the fanfare of Saturn's resplendent rings, but as with Saturn, moons play a key role in supplying the particles that make up the giant disks.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Adam Hadhazy is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He often writes about physics, psychology, animal behavior and story topics in general that explore the blurring line between today's science fiction and tomorrow's science fact. Adam has a Master of Arts degree from the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Boston College. When not squeezing in reruns of Star Trek, Adam likes hurling a Frisbee or dining on spicy food. You can check out more of his work at www.adamhadhazy.com.