Saturn Solstice: Cassini Gets 'Ringside Seat' to Dramatic Seasonal Changes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

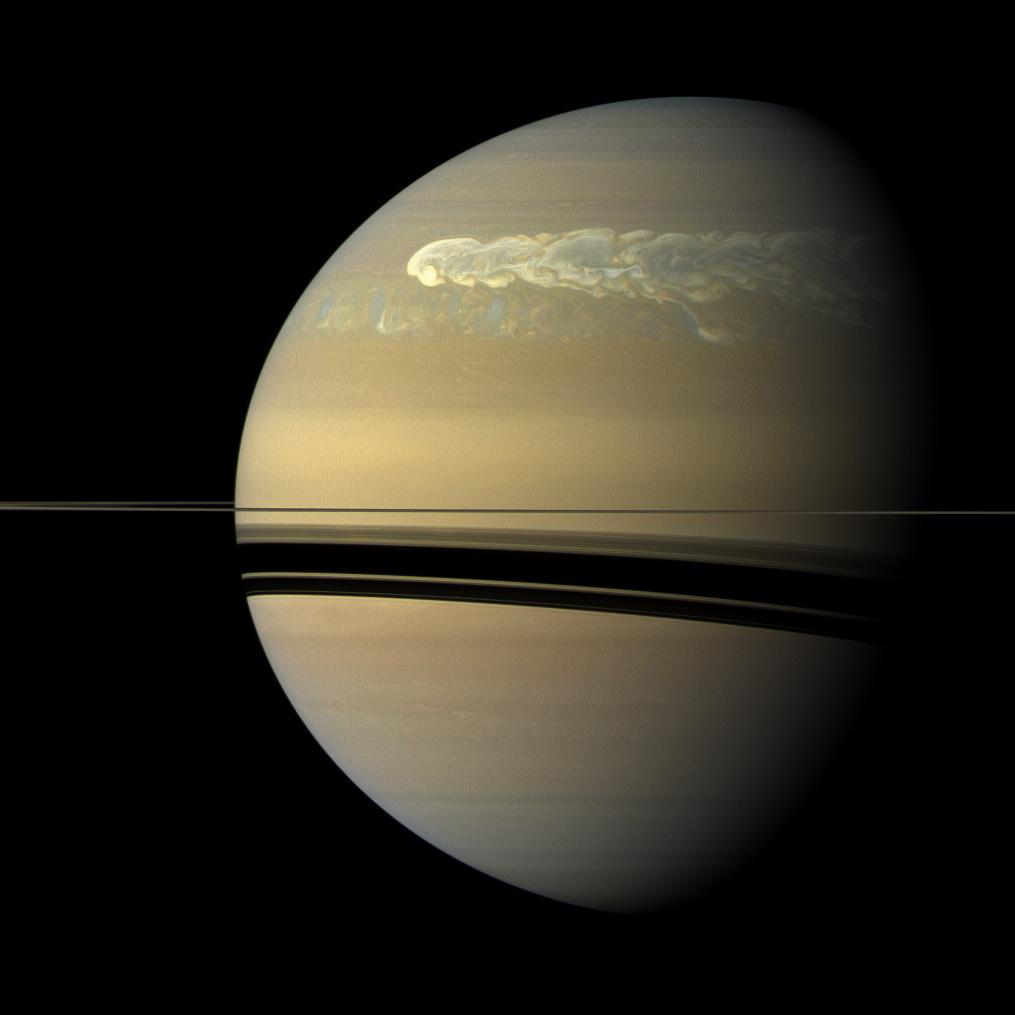

The Cassini spacecraft at Saturn watched over the ringed planet's solstice Wednesday (May 24), accomplishing the main goal of its second extended mission. A solstice occurs on Saturn roughly every 15 Earth years as its seasons change.

Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004, and the spacecraft completed its primary mission to study the planet, its rings and its moons by 2008. Its first extended mission, which lasted until 2010, was to observe the system during the planet's equinox, when the sun strikes the rings edge-on and the days are of equal length on the north and south poles. The goal of its second extended mission — a seven-year plan called the Solstice Mission — was to observe all the way up to the north pole's summer solstice (when the days are longest at Saturn's north pole, and shortest at the planet's south pole) and investigate the system's seasonal changes.

"During Cassini's Solstice Mission, we have witnessed — up close for the first time — an entire season at Saturn," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, said in a statement. "The Saturn system undergoes dramatic transitions from winter to summer, and thanks to Cassini, we had a ringside seat." [Epic Cassini Mission to Saturn Gets Awesome Video Treatment]

During the Solstice Mission, researchers watched a huge storm encircle the planet and disperse over the course of seven months. They watched the hexagonal jet stream surrounding Saturn's north pole change from blue to yellow (except for the very center) over the course of the northern hemisphere's spring.

Cassini data suggests that the increased sunlight interacts with compounds in the upper atmosphere to form particles called photochemical aerosols, which accumulate into a yellowish haze. The very center may stay blue for one of two reasons, researchers said in an image caption: it hasn't been exposed to sunlight as long as the areas around it because it's at the very top of the planet, or the circulation in the whirling vortex pulls the compounds downward.

Cassini saw the seasonal changes come over the planet suddenly based on latitude, rather than gradually, the researchers said.

"Eventually, a whole hemisphere undergoes change, but it gets there by these jumps at specific latitude bands at different times in the season," Robert West, a member of Cassini's imaging team at JPL, said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The solstice's intense sunlight heated Saturn's rings, letting Cassini's instruments better investigate ring particles' composition and the way they clump together. The planet's orientation compared to the sun and Earth, with its rings tipped maximally toward Earth, also meant that Cassini could easily send a radio signal through the densest part of the rings to investigate, according to the statement.

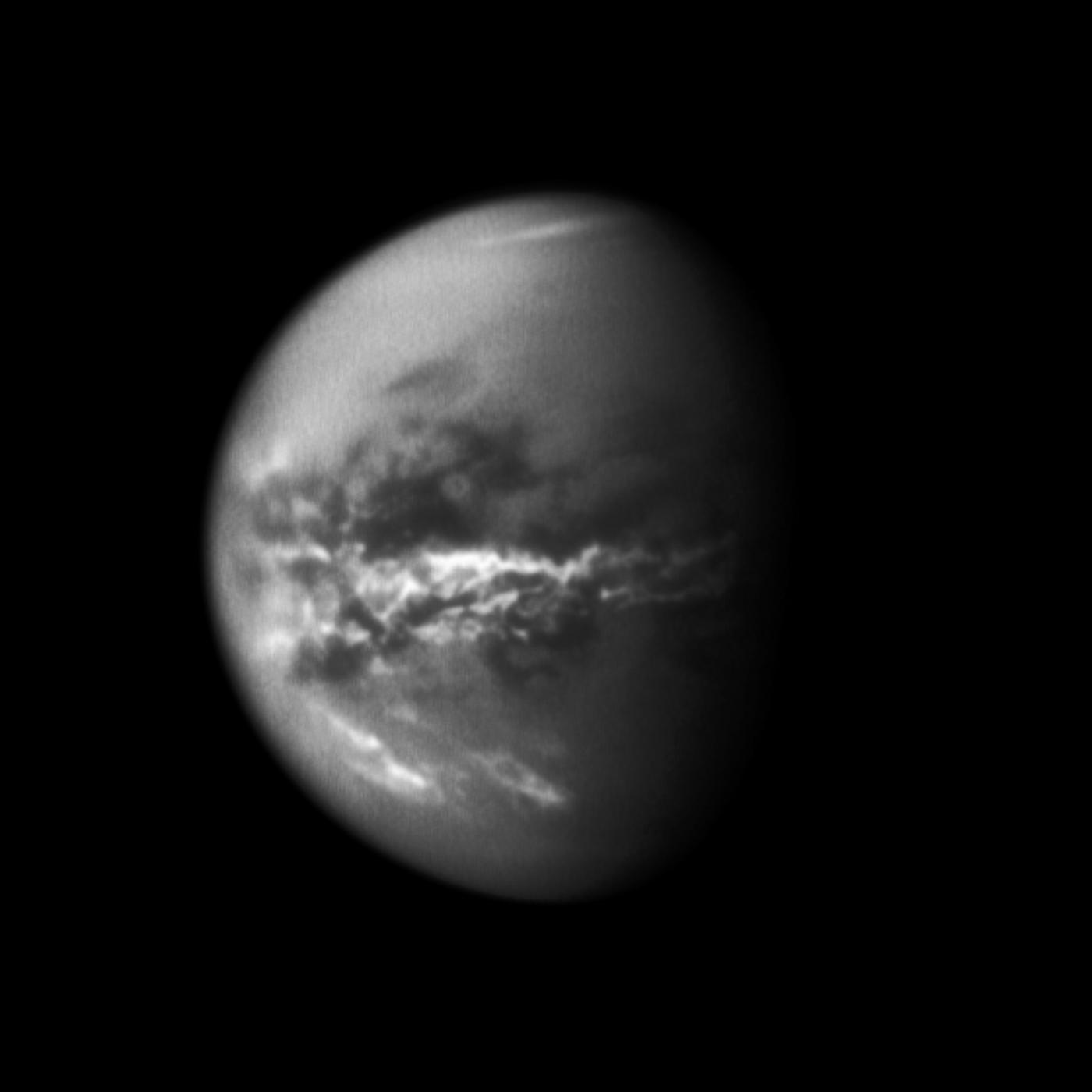

On Saturn's largest moon, Titan, methane storm clouds shifted up from the south toward the moon's equator from 2004 to 2010. Their corresponding shift northward as the solstice approached was surprisingly slow; according to the statement, cloud models had expected the activity to happen years earlier.

But some action was sudden: In 2013, haze and trace hydrocarbons formerly found only in the north suddenly built up in the Titan's south, indicating that its atmospheric circulation had changed direction due to the changing sun exposure, the statement said.

"Observations of how the locations of cloud activity change and how long such changes take give us important information about the workings of Titan's atmosphere and also its surface, as rainfall and wind patterns change with the seasons too," Elizabeth Turtle, a researcher on Cassini's imaging team at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, said in the statement.

And on Saturn's moon Enceladus, which hosts a subsurface ocean and blasts geysers of material out through its plumes, the main seasonal change was its southern hemisphere's transition to winter darkness. This change let Cassini monitor the moon's temperature more easily, to investigate the intriguing moon.

Cassini is in the middle of the "Grand Finale" phase of its mission, in which it is diving between Saturn and its rings repeatedly to investigate the planet more closely than ever before. Once it finishes seeing the planet through the change of seasons and charting its moons, rings and surface as deeply as possible, Cassini will plunge into Saturn's atmosphere on Sept. 15. The mission is a collaboration among NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.