Saturn's Moons and Rings May Be Younger Than the Dinosaurs

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

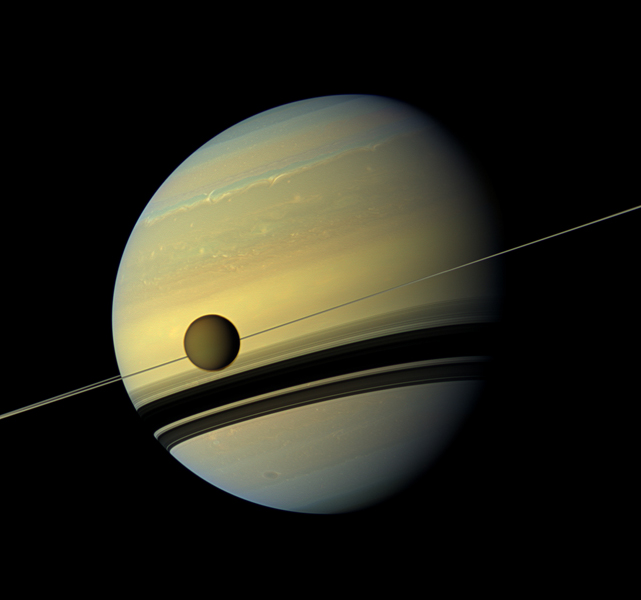

Some of Saturn's icy moons may have been formed after many dinosaurs roamed the Earth. New computer modeling of the Saturnian system suggests the rings and moons may be no more than 100 million years old.

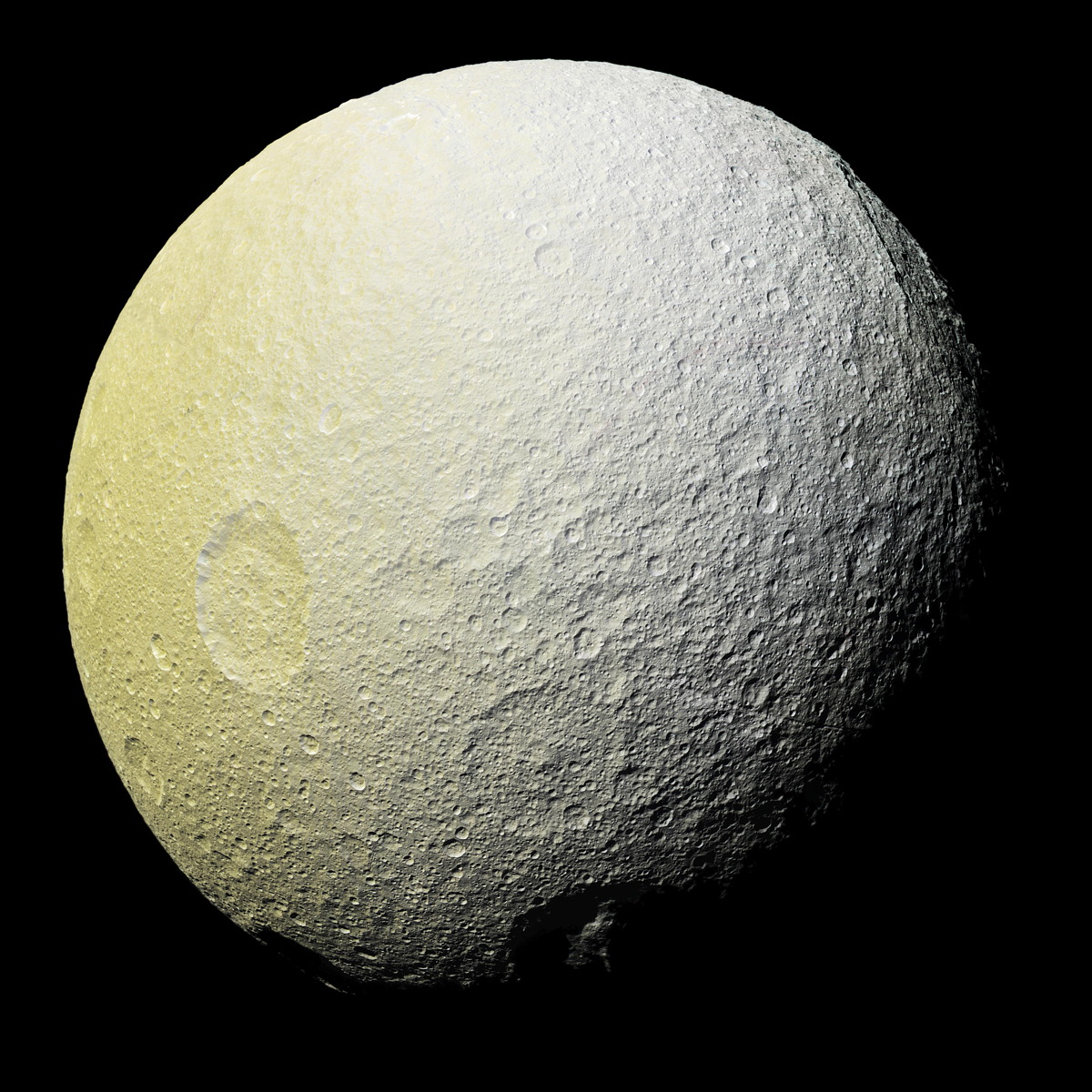

Saturn hosts 62 known moons. All of them are influenced not only by the gravity of the planet, but also by each other's gravities. A new computer model suggests that the Saturnian moons Tethys, Dione and Rhea haven't seen the kinds of changes in their orbital tilts that are typical for moons that have lived in the system and interacted with other moons over long periods of time. In other words, these appear to be very young moons.

"Moons are always changing their orbits. That's inevitable," Matija Cuk, principal investigator at the SETI Institute and one of the authors of the new research, said in a statement. "But that fact allows us to use computer simulations to tease out the history of Saturn's inner moons. Doing so, we find that they were most likely born during the most recent 2 percent of the planet's history." [Saturn Photos: Latest Images from NASA's Cassini Orbiter]

The age of Saturn's rings has come under considerable debate since their discovery in the 1600s. In 2012, however, French astronomers suggested that some of the inner moons and the planet's well-known rings may have recent origins. The researchers showed that tidal effects — which refer to "the gravitational interaction of the inner moons with fluids deep in Saturn’s interior," according to the statement — should cause the moons to move to larger orbits in a very short time.

"Saturn has dozens of moons that are slowly increasing their orbital size due to tidal effects. In addition, pairs of moons may occasionally move into orbital resonances. This occurs when one moon's orbital period becomes a simple fraction of another. For example, one moon could orbit twice as fast as another moon, or three times as fast.

Once an orbital resonance takes place, the moons can affect each other's gravity, even if they are very small. This will eventually elongate their orbits and tilt them from their original orbital plane.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By looking at computer models that predict how extended a moon's orbit should become over time, and comparing that with the actual position of the moon today, the researchers found that the orbits of Tethys, Dione and Rhea are "less dramatically altered than previously thought," the statement said. The moons don't appear to have moved very far from where they were born.

To get a more specific value for the ages of these moons, Cuk used ice geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus. The researchers assumed that the energy powering those geysers comes from tidal interactions with Saturn and that the level of geothermal activity on Enceladus has been constant, and from there, inferred the strength of the tidal forces from Saturn.

Using the computer simulations, the researchers concluded that Enceladus would have moved from its original orbital position to its current one in just 100 million years — meaning it likely formed during the Cretaceous period. The larger implication is that the inner moons of Saturn and its gorgeous rings are all relatively young. (The more distant moons Titan and Iapetus would not have been formed at the same time.)

"So the question arises — what caused the recent birth of the inner moons?" Cuk said in the statement. "Our best guess is that Saturn had a similar collection of moons before, but their orbits were disturbed by a special kind of orbital resonance involving Saturn's motion around the sun. Eventually, the orbits of neighboring moons crossed, and these objects collided. From this rubble, the present set of moons and rings formed."

The research is being published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow Space.com @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.