Orion the Hunter: Spot Beloved Constellation Overhead Now

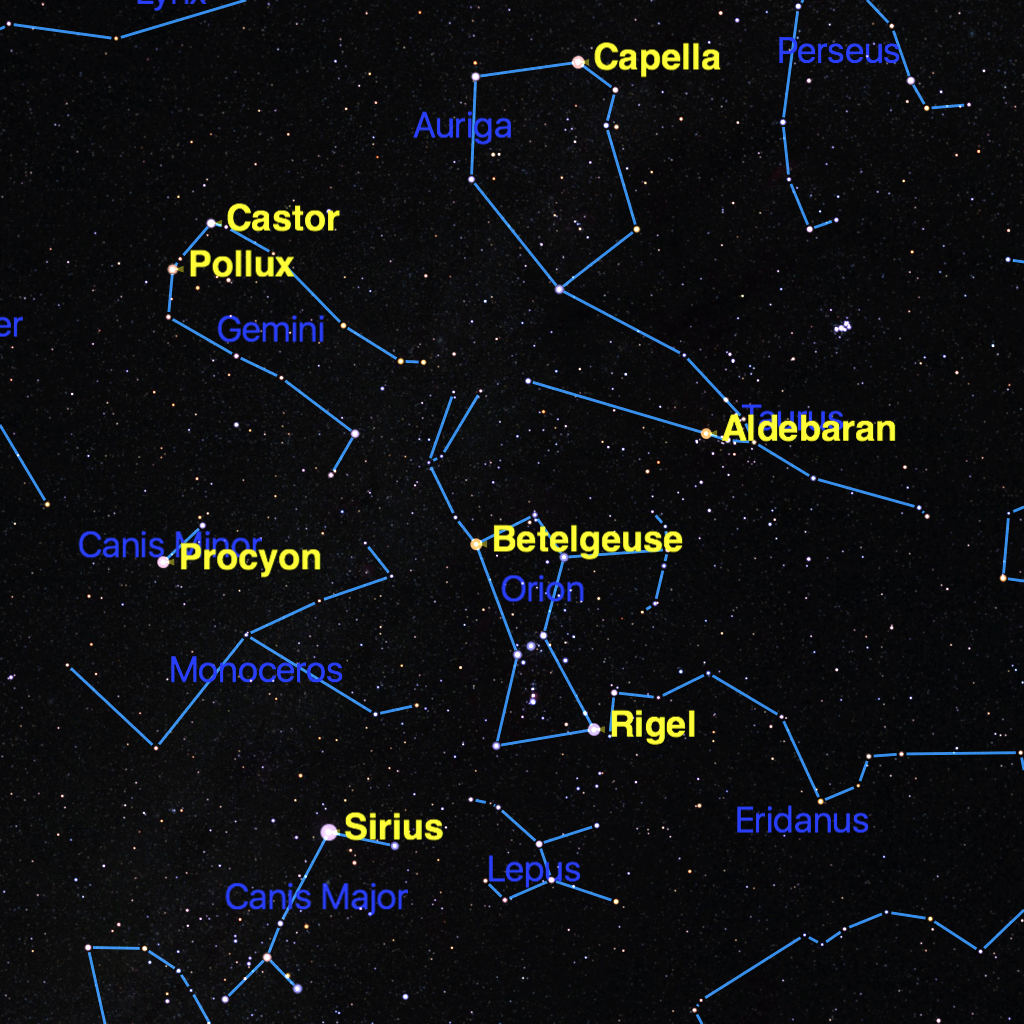

Step outside on any evening this month and look toward the south. You will see one of the best-loved constellations, Orion the Hunter, surrounded by a circle of six brilliant stars.

Orion is one of the best-known star patterns in the night sky, along with the Big Dipper. If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, the Big Dipper is always somewhere in the northern sky, because it is a "circumpolar constellation" — it lies close to the north celestial pole and circles the pole constantly.

Orion, on the other hand, is located on the celestial equator, so it's only visible part of the year. -Orion is best-placed for viewing in January and February. [January 2016 Skywatching: Orange Giant Star, Planets and More (Video)]

The Orion constellation has a very striking pattern in its stars. Four bright stars mark the Hunter's shoulders and knees: Betelgeuse and Bellatrix are his shoulders and Saiph and Rigel are his knees. In the middle of the rectangle formed by these four stars are three stars on a slant, representing Orion's belt, with three smaller stars below for his sword. Above and between his shoulders is a small triangle of stars representing his rather tiny head.

Betelgeuse and Rigel are two of the brightest stars in the sky, but they're very different from each other. Betelgeuse is an ancient, red-giant star that lies 500 light-years from the sun and is nearly 700 times wider than Earth's star. Rigel, on the other hand, is 900 light-years distant and is a young blue giant, 90 times the diameter of the sun. If you look closely, you can distinguish the difference in color between the two stars.

The three stars that form Orion's belt, which seem so perfectly placed in our sky, are actually nowhere near each other in space. The two outer stars, Alnitak and Mintaka, are relatively close to us at 700 light-years, but the middle star, Alnilam, is nearly three times more distant, at 2,000 light-years.

The three stars that appear to line up to form Orion's sword are also an illusion of perspective. From north to south, they are 830, 1,920 and 1,860 light-years away. Thus, the stars that make up Orion are actually spread over thousands of light-years of space, and only appear as a group here on Earth by an accident of perspective.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Look closely at the middle star in Orion's sword, called the Trapezium. To the naked eye it appears a little bit fuzzy; this fuzziness becomes obvious in binoculars or through a small telescope. What you are seeing is the Orion Nebula, a vast cloud of glowing gas that is the nursery for a new star cluster.

Grouped around Orion are six bright stars that form a rough circle. Once you see Orion, it becomes easy to identify the stars around it. Remember that east and west in the sky are the opposite of the directions we're familiar with on maps of the Earth, because we are looking outward.

Orion's three belt stars point northwestward toward Aldebaran, another red-giant star, in the constellation Taurus the Bull. High over Orion's head is Capella, in the constellation Auriga the Charioteer.

Rigel and Betelgeuse point toward the twin stars Castor and Pollux, in Gemini the Twins. East of Orion is Procyon in Canis Minor, the Little Dog, and the belt stars point southeastward to Sirius in Canis Major, the Big Dog.

These six stars are all bright because they are relatively close to the sun, whereas the stars in Orion are all much more distant. Sirius is nearest at only 8.6 light-years away, and Procyon is not much farther at 11.5 light-years. Castor, Pollux and Capella are all between 34 and 52 light-years distant, and Aldebaran is 67 light-years away.

When you look at these stars on a crisp winter night on Earth, be aware that they are actually scattered far and wide through the depths of space.

Editor's note: If you capture a great photo of a night-sky sight and want to share it with us and our news partners for a story or gallery, we want to know. Send your images and comments in to: spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com bySimulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Nightand SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.