Captains of Spaceflight Industry Talk Trends and Big Dreams

The space industry is moving closer to a point where government agencies won't be the only dominating players, and when a wide range of companies can find or create profitable ventures high above the surface of the Earth. But how and when will the industry arrive at that tipping point?

A panel of spaceflight industry leaders discussed those questions at the first SpaceCom Expo (Space Commerce Conference and Exposition), held in Houston in November. The meeting aimed to bring together not only companies and agencies already involved in the space industry, but also those from industries that are beginning to find business opportunities in space.

One panel discussion at the meeting featured some of the people who are leading the effort to grow business in space, through an increase in microgravity science, space tourism, cargo and crew delivery, and other ventures. The panelists discussed where new opportunities are springing up, what will happen to the International Space Station in the next decade and how suborbital spaceflight can serve as a stepping-stone for growing space business that will take place in even more distant locations. [6 Private Companies That Could Launch Humans Into Space]

The panel was composed of Frank Culbertson, a former astronaut and president of Orbital ATK's space systems group; Jeff Greason, a founder and former CTO of the private spaceflight company XCOR Aerospace; Greg Johnson, president and executive director of the nonprofit group the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS), which manages science experiments on the International Space Station; Jeffrey Manber, CEO of NanoRacks, a company that helps other businesses get science experiments and small satellites into orbit; and Erika Wagner, business development manager for Blue Origin, a private spaceflight company founded by Amazon.com CEO Jeff Bezos.

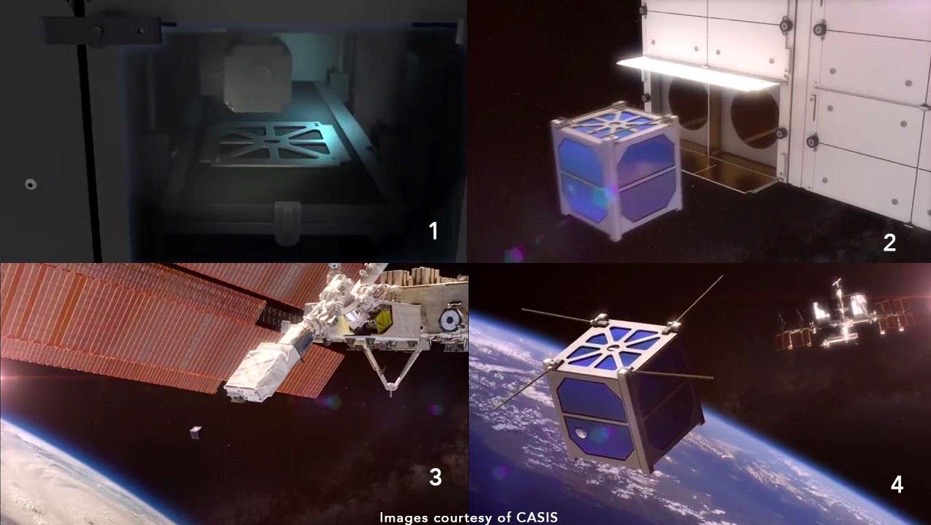

Small satellites and science

One of the places where the commercial space industry appears to be growing most rapidly is in the demand for small satellites, like cubesats (which are often smaller than a loaf of bread). Culbertson mentioned that there seem to be more companies taking advantage of small satellite observations of the Earth than ever before. For example, a new business called Space Applications Catapult is helping companies use publicly available satellite data of the Earth for everything from climate studies to tracking large groups of jellyfish before they clog up cooling systems at nuclear power planets. Talks at SpaceCom indicated that there are many other companies finding potential applications for small satellite data. There's even talk of building satellites in orbit.

With the size of satellites going down, and the number of companies that launch the objects going up, the panelists said space is effectively getting cheaper. Many people are now comparing the space industry with the information technology industry — specifically, the boom of companies that make apps, software, websites and related products. This comparison is meant to suggest that the space industry is becoming a place where a very small company with a good idea has the potential to reap massive profits; the biggest examples of this in the tech world would be Facebook or Google, but many other companies have seen this kind of success on a smaller scale, the panelists said.

"Most of those technology success stories start with a couple of people in a garage somewhere," said Greason. "What's happening is now we're on the threshold of where you can start a space company with a couple of people in a garage. … Now you don't have to build an entire satellite-manufacturing company and [a] launch company and all the rest of those other things to get something in space. You can just put together a couple of small satellites and have somebody put them up there for you. … In a sense, space access is going from wholesale to retail. It's going to something where you can actually afford to buy a little of it, get started and find out if you have a product."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another area of the commercial space market that appears to be growing is microgravity science. There is an increasing number of ways for companies to get experiments onto rockets that undergo a few moments of weightlessness, or that pass through the upper layers of the atmosphere; there are also more ways to get experiments on the International Space Station, to test the effects of microgravity on all kinds of systems, Culbertson said.

"If you have something that you mix, something that you flow, something that you melt or something that you grow, you're probably being impacted by gravity," Wagner said, noting that companies to whom this applies could have a reason to test the effect of microgravity on their product or process. In fact, Wagner said, she feels that "innovation is going to come from outside the space industry," and that it may be private companies and other commercial users who come up with new space-based ventures and ultimately find ways to make space profitable.

Johnson said that over "half of our pipeline" at CASIS is "coming from … commercial companies," and he said the organization is finding more "nontraditional" customers, or those that may not have previously had a reason to utilize a microgravity environment to advance their work or their product. He added that there are more private companies covering the incremental costs of sending their experiments into space (the base costs, including transportation, astronauts and the cost of the station are still covered by NASA). "That's very, very promising to us," he said.

Blue Origin is one company that may open up new opportunities for microgravity science. The business has advertised its New Shepard suborbital vehicle as both a tourism spacecraft and a science laboratory. If New Shepard works the way the company would like, people could not only send experiments into microgravity, but also send up a scientist, meaning the human passenger could execute more-complex experiments. The Sierra Nevada Corporation Dream Chaser space plane could potentially do the same, company representatives have said. Sierra Nevada is primarily an integrator and electronic systems provider, but the company has also developed a space systems branch.

However, Blue Origin is not yet selling these opportunities customers; it's still in the testing phase on its New Shepard suborbital vehicle. But the company NanoRacks is an operational example of the increasing accessibility of sending satellites and science experiments into space. The company has helped many scientists get experiments into space, Manber said.

"At NanoRacks, we're implementers," Manber said. "We saw that there was a need and a demand for small satellites in the near term, not in the decade. We were able to work with NASA, with CASIS, and invest our own funds, and we're now deploying 90 cubesats off the space station. … When we see there's a demand, we'll go out and follow the commercial pathway. The situation we have now … is that you can invest your own capital for your idea, and implementers like us will help you do it.

"We're on a cusp of a moment where space will be just another place to do business," Manber said. "And for me, that's terribly exciting."

ISS phase-out

One of the big questions hovering over the spaceflight industry is what will happen to the International Space Station when NASA decides to stop funding the orbiting lab. The station serves largely as a microgravity laboratory, with dozens or hundreds experiments happening on board

at any given time. NASA has committed to maintaining its investment in the station until 2024 (the station is jointly supported by the U.S., Europe, Russia, Canada and Japan), but NASA officials have said they want to put their financial resources toward projects that will take humans beyond low-Earth orbit, like back to the moon or to Mars.

But the loss of the only major space laboratory currently in operation would be devastating to researchers (and companies) that want to do experiments in microgravity. The panelists and other leaders at the meeting stressed that if the spaceflight industry wants to continue to grow, there must be a backup plan in place. To avoid a catastrophe, there is discussion about how the commercial spaceflight industry might take responsibility for the station, or build a new one. No concrete plans have emerged, however.

"You don't want to phase out [the space station] until it's assured 100 percent there will be a commercial presence," Manber said. "So this is a very interesting time. It's a very interesting problem — how do you make a transition at that extremely important moment?

"For me, I think it's extremely important that we have a definitive deadline," he continued. "Whatever it is — we may disagree whether it's 2024 or 2028 for the life of the space station — but … you need to have the United States [government] stand up sooner rather than later and say, 'Here's the last year. Beyond that, we will support — commercially, as a customer — these services on these platforms.'"

Industry experts, both at SpaceCom and at other industry meetings, have said NASA will very likely maintain some human presence in low-Earth orbit. That's because the lessons and skills obtained there are necessary if the agency hopes to send humans on longer space trips that may take astronauts much farther from home. In the future, the station could be a joint operation between the U.S. government and private industry. But to get private companies to pick up the load currently carried by NASA, there needs to be the promise of profit. And the discussions being held at industry meetings suggest there is still no guarantee that the marketplace will grow enough to make investors want to take that leap.

Suborbital to orbital

One day, space may resemble the dream that is currently floating around the collective industry consciousness: There might be multiple science laboratories orbiting the Earth, along with destinations for space tourists. Products that use satellite data could be as common as social media platforms. NASA may be sending astronauts (and cargo) to the moon or to Mars, with multiple private companies helping the agency do it.

But there's still a long way to go to reach that dream, and one of the stepping-stones to getting there will be suborbital spaceflight, some of the panelists said.

There are multiple companies that currently launch rockets into suborbital space, and a few that are working toward regular, reliable systems of human suborbital spaceflight. Those companies could offer space tourism and astronaut training, as well as microgravity science laboratories, but the businesses could also provide a testing ground for companies that want to go to orbital space, Wagner said.

"[Suborbital] offers that easier entrance point," Wagner said. "We've been talking to our friends at CASIS about how do we build a pipeline of research and development projects that start in suborbital spaceflight — because you can get there fast, you can get there cheaply, you can get there in ways that are great for risk reduction and preliminary data. And then you can grow your technologies and your portfolio in ways that make a lot more sense on the International Space Station. I think that we're seeing suborbital as a jumping-off point. It's a jumping-off point for people who want to enter the market. It's a jumping-off point for technologies that [people] want to be trialed. And it is a way you can buy space in uniquely accessible chunks."

Wagner said suborbital could also change how space is introduced into education. With the way the industry is going, it's possible for students to design, build and fly an experiment within the course of a single school year, and even have time to analyze the data for a research project or

science fair presentation. That's in contrast to past decades, she said, when that time line was typically stretched over many years or a decade.

Greason emphasized that suborbital offers the opportunity to test technologies, something sorely lacking in the current industry because of the high risk paired with the high financial commitment.

"One of the great things about frequent access to suborbital flight is you can just try things," Greason said.

Currently, the hurdles of money and access are "so huge" in spaceflight, Greason said, that companies are "mostly concerned with not screwing up." As a result, they predominantly use technologies and approaches that are already well-tested, and there is very little growth and development. With increased access to suborbital spaceflight, and lowered cost, companies can fly their projects "20 or 30 or 40 or 50 or 60 times, tweaking it a little bit 'til it works every time. And now you're ready to go to a satellite or to the space station."

With the ability to prove technologies "in actual spaceflight, cheaply and quickly," Greason expects to see "much more aggressive technologies" than those that have been developed in the "more traditional space approach," he said. "And that's going to be a very big deal."

Commuting to space

There are lots of new business opportunities blooming in space, Culbertson said in his first remarks during the panel discussion. He reviewed, in broad strokes, some of the specific areas where the space industry is growing.

The area that "tends to get the headlines" consists of the new ventures in human spaceflight, Culbertson said. There are now a handful of commercial companies — like Blue Origin, SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and XCOR — that have said they will offer opportunities for "space tourism," meaning average citizens could purchase a ticket on some kind of space vehicle and take a ride. At the moment, it is unclear when the first space tourists will actually fly, although some of those companies have set target dates in the mid-2020s. But as early as 2017, SpaceX and Boeing may be flying human astronauts to the International Space Station. Both companies have been hired by NASA to build vehicles that will replace the Russian Soyuz as the only spacecraft that can currently transport humans to orbit.

But the dreams of spaceflight industry leaders go well beyond the next two decades. Discussions at the meeting occasionally touched on bigger questions about human spaceflight, such as when there will be a need to bring people to space the way commuter trains transport a workforce from the suburbs to the city. The answer, Greason said, is the same as it is for any Earth-based industry: when the cost of transporting people is lower than the profit that can be made from the work they do.

"People fundamentally misunderstand the economics of human beings in space, because we haven't had, in some sense, an economics of human beings in space yet," Greason said. "It's not qualitatively different than flying human beings up to an oil platform. They have jobs to do. They have something up there that needs to get done. That's why they're there to do it."

It's unlikely that this image of commercial astronauts going to work in space will become a reality if the cost of spaceflight does not go down. Right now, one trip to space aboard a Russian Soyuz vehicle costs NASA $70 million. The cost of launch will drop as commercial companies begin their space-transportation programs and build reusable rockets. But there are many other cost elements, such as supplies and habitat for the astronaut, and paying the necessary staff on the ground.

"All of those have the potential to come down," Greason said.

"When [the cost of putting a human in space] comes down below a certain threshold price, the expansion of human activity in space on a commercial basis is going to be huge," he said. "It's not going to happen incrementally. It's going to be suddenly one day where you can make one dollar more by putting a person up than it cost you to put that person up. Well, guess what, the next day, we're going to start putting up a lot of people."

Greason continued this line of thought even further into the future, to a time when the idea of people living in space is no longer a science fiction concept. The thought of private industry running operations in space was "a laughable notion 25 years ago. Now it's orthodox." Similarly, people might think it inconceivable that someone, a few decades from now, will "wake up in the morning and they're not going to think of Earth as their home."

"And we're not ready for that," Greason said. "We don't have a legal structure, a social structure. We're not thinking about it."

But perhaps it's time for people to start getting used to that idea.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter