Total Lunar Eclipse Will Bring a Moon Triple Treat Sunday

This Sunday night moon observers have the chance to see a lunar triple treat, weather permitting.

First, the moon will be full, as it always must be for a lunar eclipse to occur. This is a special full moon, because this is the Harvest Moon. Because the angle of the ecliptic —the path the moon and planets follow across the sky —is low to the horizon, the moon rises about the same time every night, giving farmers an extra supply of light when they most need it, at harvest time.

Second, the full moon will be at its closest to Earth in all of 2015, what is known to astronomers as a "perigee moon." In recent years this has become known as a "supermoon." Perigee (meaning "closest to Earth") occurs at 10 p.m. EDT, the moon being a mere 222,374 miles (357,877 km) from Earth. [Supermoon Lunar Eclipse: When and Where to See It]

In fact, the human eye can't detect the 5-percent difference in size between the moon at perigee and the moon at apogee (farthest from Earth), but everyone who looks at the moon Sunday night (Sept. 27) will swear it looks bigger than usual. Partly that is because, when seen low on the horizon, the human eye and brain combine to create an optical illusion known as the moon illusion, whereby the moon (and other objects) viewed close to the horizon seem larger than when seen overhead. Cover the moon with a dime at arm's length, and you'll see that there is no difference.

The only noticeable effect of a perigee moon is that the ocean tides will be a bit higher than usual for the day of the full moon and the next three days.

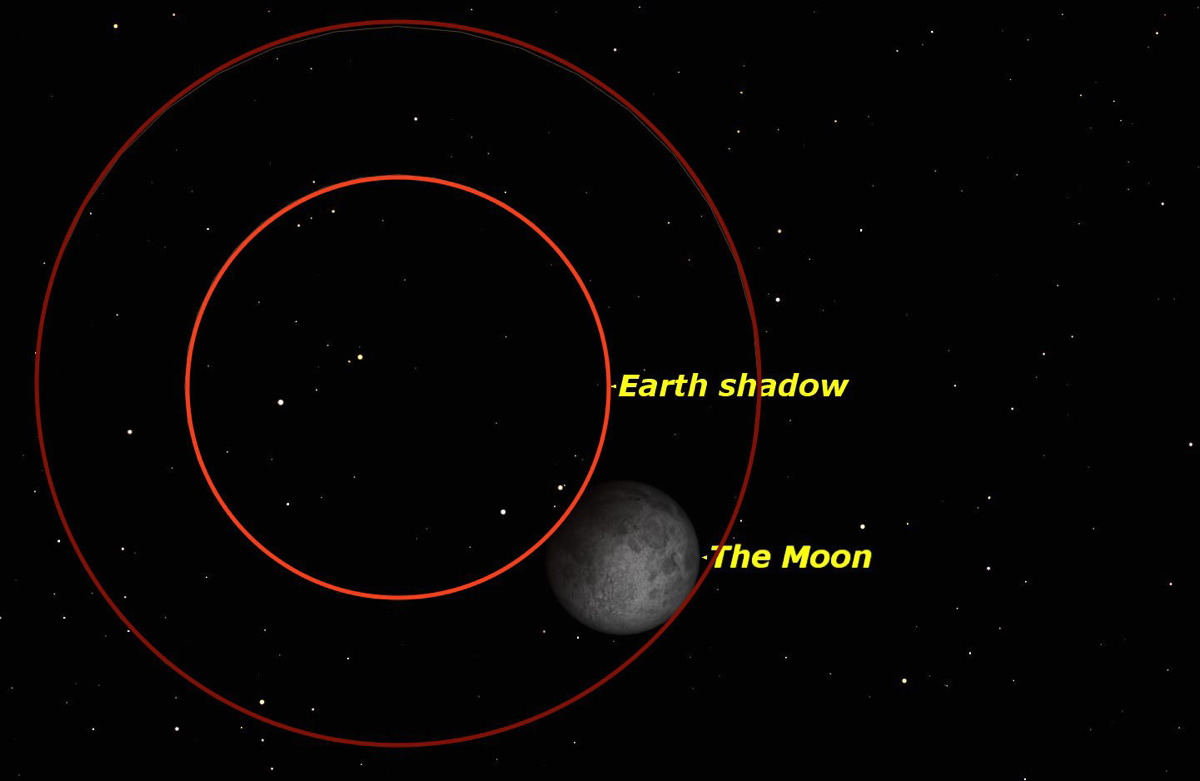

The third, and most important part of this treat, is that we will have a total eclipse of the moon. At most full moons, the sun, Earth and moon line up approximately, but because of the tilt of the moon's orbit, the moon passes above or below the Earth's shadow, and avoids being eclipsed.

At certain points in the moon's orbit, sun, Earth and moon line up exactly, and the Earth's shadow falls across the face of the moon, and we have a lunar eclipse. This is what will happen Sunday night. [Supermoon Lunar Eclipse: Viewing Maps]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The moon's shadow has two parts: a darker inner part called the umbra, and a lighter outer part called the penumbra. This is because the sun is not a point source of light, so its light leaks around the edge of the Earth, and results in an unsharp shadow. In passing through the Earth's atmosphere, the light turns red or orange, so that the light that actually reaches the moon is tinted by thousands of sunsets and sunrises all around the periphery of the Earth.

One result of these multiple sunrises and sunsets is that the moon during an eclipse is often tinted red, which is the origin of the idea of a lunar eclipse being a "Blood Moon." It isn't a far stretch of the human imagination to turn this Blood Moon into a portent of disaster.

A lot has been made in the media of this eclipse being the final event in a foursome of total eclipses known as a "lunar tetrad." There is nothing unusual about four lunar eclipses in two years, since we usually average at least two lunar eclipses every year, though not all are total.

In fact, there was no tetrad of total eclipses at all, because the last lunar eclipse, on April 4, was not really a total eclipse. According to the usual way of calculating eclipses, the moon spent only 4.5 minutes in the umbral shadow, but recently this calculation method has been corrected, resulting in the April eclipse failing to be total at all.

This Sunday's lunar eclipse is a true total eclipse, with the moon being in the umbra for a full 1 hour and 22 minutes.

Observers in eastern and central regions of North America will get to see the whole eclipse; those farther west will see the moon rise already partially eclipsed. Observers in Europe and Africa will see the eclipse before dawn on Monday (Sept. 28).

This brings up the question of dates and times, which often causes confusion. Even a usually reliable source like Canada's Weather Network got the date of this eclipse wrong.

Officially, mid-eclipse occurs Sept. 28 at 02:47 Universal Time, which is the same as Greenwich Mean Time (but not British Summer Time). Subtracting 4 hours, this places mid-eclipse in the Eastern Daylight Time zone at 10:47 p.m. on Sept. 27; the date changes at midnight. So be sure you look for the eclipse on Sunday evening. If you wait until Monday evening, you will be a day late.

Here are the important times in Eastern Daylight Time; if you're using CDT, MDT, or PDT, the times will be earlier by 1, 2 or 3 hours.

All times in EDT

- 8:11:46 p.m. — Moon enters penumbra

- 9:07:12 p.m. — Moon enters outer edge of umbra

- 10:11:11 p.m. — Moon completely in umbra

- 10:47:09 p.m. — Mid-eclipse

- 11:23:07 p.m. — Moon begins to emerge from umbra

- 12:27:06 a.m. — Moon completely out of umbra

- 1:22:33 a.m. — Moon leaves penumbra

As always, we look forward to your pictures of this beautiful event.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing picture of the Sept. 27 supermoon lunar eclipse and would like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.