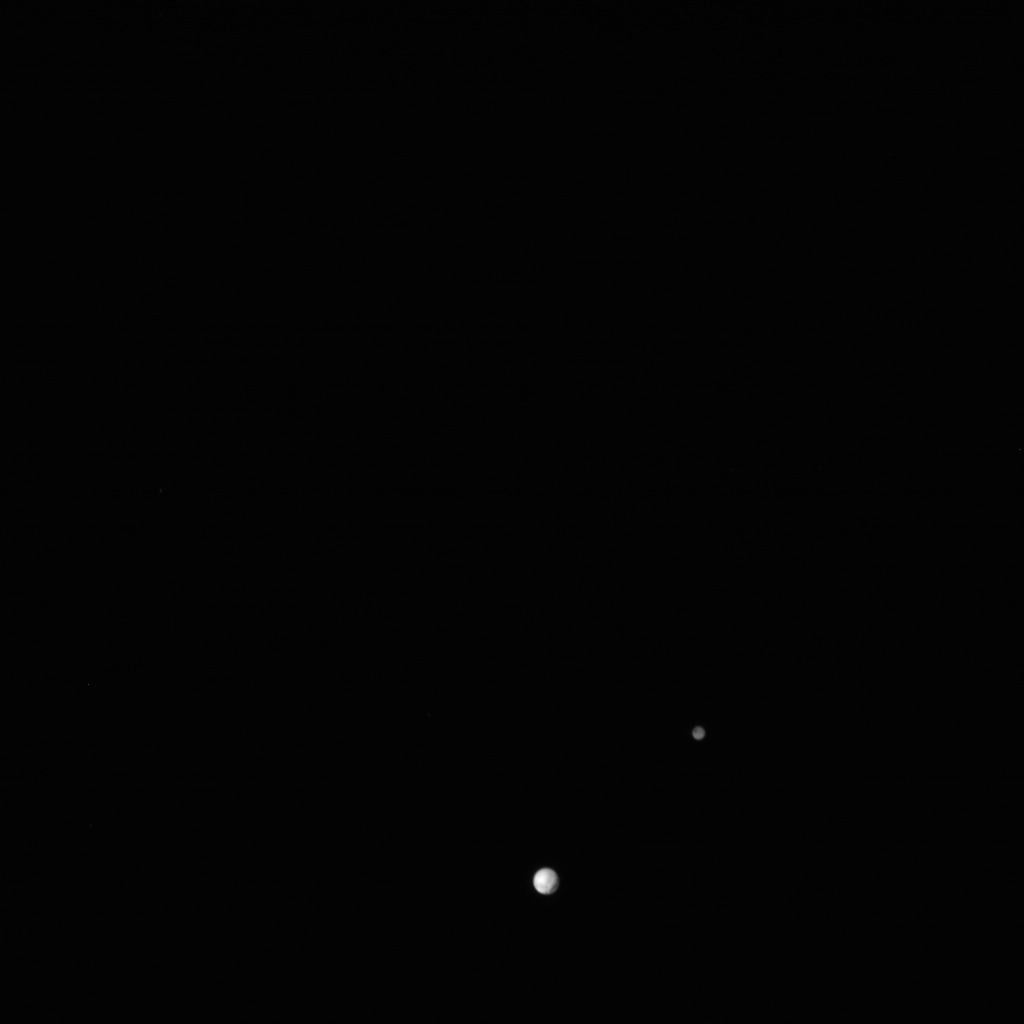

Pluto and Charon Starting to Come into Focus (Photo)

Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, posed for a solemn portrait taken by NASA's New Horizon's probe, which is only two weeks away from its close encounter with the dwarf planet.

The newest snapshot of Pluto and Charon shows two icy gray circles hovering in a pitch-black void. In previous images, the two objects often looked like highly pixelated smudges of color — barely distinguishable as spheres. But with New Horizons only about 10 million miles (16 million kilometers) away from Pluto (and closing that distance by more than 30,000 miles, or 48,000 km, every hour), the view of these unexplored worlds is getting clearer every day.

"Looking at pictures on the website, you can see that Pluto and Charon are becoming more distinct in their surface features," Alice Bowman, the missions operations manager for New Horizons, said today (June 30) in a mission update. "It's getting pretty exciting. And every day is bringing new features into light." [New Horizons' Pluto Imagery Will Amaze Us (Video)]

New Horizons launched in January of 2006 and has spent the last nine-plus years making its way toward Pluto and the region of icy bodies beyond Neptune, known as the Kuiper Belt. Although four other human-made probes have ventured past the orbit of Neptune, none have done a close study of Pluto and its moons. Even the Hubble Space Telescope's images of this small, dim dwarf planet are highly pixelated and blurry. New Horizons hopes to reveal a detailed look at the surface of Pluto, study its atmosphere and much more.

The new portrait of Pluto and Charon was taken by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) instrument onboard New Horizons. These images are not only for scientific and aesthetic purposes, but also for navigational ones, according to a statement from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland (mission control for New Horizons).

With nearly 3 billion miles (4.8 billion km) between them, it takes about 4.5 hours to send a signal from the Maryland control center to New Horizons, Bowman said. As a result, team members have to tell the probe what to do (such as which instruments to point at Pluto) long before the probe actually does it. When the probe makes its close flyby of Pluto on July 14, the team will not be able to make any last-minute adjustments. Instead, New Horizons runs prewritten command sequences, most of which were written years before they were executed.

The command sequences must also indicate where Pluto is located relative to the probe, and thus where New Horizons should point its instruments. The New Horizons team has been constantly updating that navigational information as the probe moves closer and can obtain more precise information about Pluto's location. Earlier this month, the team executed a course correction to ensure the spacecraft didn't arrive at its close encounter point too early; that kind of miscalculation could cause the probe to take photos of empty space instead of the dwarf planet, researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the next few days, Bowman said, the New Horizons team will be uploading the command sequence that will guide the probe through its historic flyby. There's also a possibility that the team will execute another course correction.

"And of course [we'll be] getting down lots of science data, optical navigation data," Bowman said. "It's going to be great."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter