Revolution in Spaceflight Requires New Spacesuits (Op-Ed)

Ted Southern is president and co-founder of Final Frontier Design, a spacesuit design company. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Spacesuits are created by science, but they can also seem magical, clothes that shield people from the inhospitable conditions of space. Spacesuits are a true paradox in design. They are both a machine and a garment. These suits must withstand large pressure differentials while remaining flexible; they must tolerate vast thermal variations inside and out, without being too heavy or stiff; they must be ultra-reliable and easy to put on.

And new designs are necessary now more than ever: Commercial space travel is set to go through a renaissance. Dozens of private companies are promising to open a new frontier to masses of people, with drastically lower prices to reach orbit; fast turnaround and reusable vehicles; and multiple options for altitude, trajectory and purpose. Space commerce promises to unveil an entirely new, virtually unlimited market of materials, engineering, science and even lifestyle. All these developments will depend on the creation of advanced spacesuits.

The list of private companies driving space travel is already vast: Boeing, Sierra Nevada, SpaceX, United Launch Alliance, Orbital Sciences and Blue Origin all compete in the field of orbital rocketry. Golden Spike, Bigelow Aerospace and Mars 1 are tackling interplanetary exploration. Virgin Galactic, XCOR and Starfighters Aerospace have set their sights on suborbital ballistic flight. Zero2Infinity and WorldView are creating high-altitude balloons that can rise more than 100,000 feet (30,000 meters). Zero Gravity Corp has already flown hundreds of zero-G parabolic flights, and Project Perlan is planning on gliding to altitudes above 90,000 feet (27,000 m) within the next year. Apologizes to anyone I missed.

Many new companies hope to capitalize on the revolution; some will not thrive, but it is possible that many will. The vast majority are owned and operated within the United States, and many are sponsored and supported in some way by NASA, by far the largest space-dedicated organization in the world, with an annual budget of over $17 billion.

A revolution in spaceflight

Each layer of the new space market promises to bloom and prosper within the decade. Several of these companies are already profit-positive, and most of them have functional hardware nearly ready for flight. Companies spend billions of dollars per year on this emerging industry.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Several reasons help explain the revolution. As personal computers have become more powerful, the complicated mathematics and science computations required for the incredible speeds, loads, temperatures and pressures of space travel have become accessible to more and more companies and individuals. Exotic materials and processes have become vastly more available to the masses within just the last 10 years, thanks largely to the Internet and the computer processor. The general policies of NASA and the outlook of Americans are increasingly supportive of private space ventures. No longer is spaceflight the realm of superpower governments, alone.

Yet, most people understand the great dangers inherent in human spaceflight. Many have lost their lives in what is just the first 53 years of human spaceflight. The great risk to human life causes real fear in this inchoate commercial frontier; one tragic incident may ruin public perception of commercial space entirely. Rand Simberg, in his recent book "Safe Is Not an Option" (Interglobal Media LLC, 2013), argues that the new space industry cannot be hindered by any restrictions on its operations, and that the government should remain hands-off with commercial space ventures. Loss of human life should be considered a regrettable, but necessary cost of pushing the boundaries of possibility, Simberg argues. NASA and the U.S. Federal Aviation Industry (FAA) should not interfere, he said.

I could not disagree more.

NASA has a proud history of participating in the commercial space industry, fostering the sector's development with satellite deployments in the 1980s, encouraging competition among garage inventors with the Centennial Challenges program, and dedicating a significant portion of the agency's budget today to the NASA Commercial Crew and Cargo Program Office (C3PO). My own company would not exist without the support of NASA, along with several of the previously listed launch providers. And without NASA's, and the FAA's, standards, recommendations and lessons learned, space entrepreneurs are bound to make the same mistakes over and over again. History can repeat itself.

The suits that make space travel possible

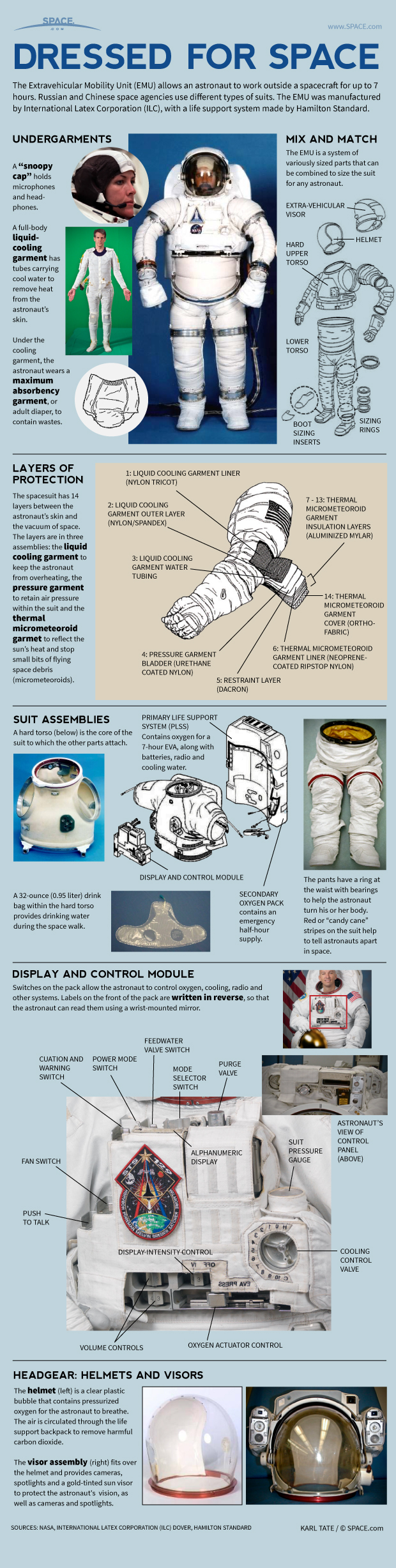

Spacesuits are a key component of the new space industry, and they come with a proud and worthy legacy: No human has ever been killed in service while wearing such a suit in space. The spacesuit has become the icon for human flight, despite the enormous complexity of the rockets and vehicles that deliver spacesuits to relevant environments. [Spacesuit Evolution in Photos]

Most people do not understand the differences between the Intra-Vehicular Activity (IVA) suit — worn for launch, re-entry and docking — versus the Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) suit — worn for spacewalking or planetary walking. While the IVA suit must provide a stable air-pressure environment for the astronaut, it does not need to withstand the thermal variations or long durations that EVA suits must endure. IVA suits do not need to be as mobile as EVA suits, either, because IVAs are generally worn pressurized only during emergencies. And most tasks designed to take place during an IVA procedure are much less motion-intensive compared to EVA procedures. The IVA suit serves as the emergency, redundant pressure vessel, the space travel equivalent of commercial airliner oxygen masks, which "fall from the panel above."

If a vehicle loses pressure above about 60,000 feet, even a mask cannot help; pilot and crew alike will lose consciousness within approximately 15 to 20 seconds. Without properly operating space suits, the extreme temperatures of those altitudes will freeze eyeballs open, and low pressure will pull the gas out of the lungs and burst eardrums.

IVA suits should also contain interfaces with parachutes, Earth survival equipment and water flotation devices, depending on the mission's flight path.

All those capabilities come at a price. As a point of comparison, according to Dennis Jenkins in his recent book "Dressing for Altitude" (2012, NASA), NASA paid more than $88,000 each for their IVA Advanced Crew Escape Suits (ACES). In 2014 dollars, that's about $180,000 each. The agency paid nearly $12 million per suit for their EVA suit, ILC Dover and Hamilton Sundstrand's Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) according to Craig Freudenrich in How Space Suits Work. In a recent RFI, NASA estimates the cost of maintenance and operations of their EMUs alone at $80 million every year for the next 10 years. These are fantastically expensive clothes, just as the space shuttle was a fantastically expensive vehicle.

EVA suits have remained an essential part of human spaceflight since the first spacewalks, in 1965. Orbital and interplanetary spaceflight require EVA systems for mission assurance, say if there is some emergency outside the vehicle, and for scientific observation; lunar and planetary human missions would be futile if humans could not walk around outside the vehicle.

However, spacesuits have historically been viewed as "contingency only" items, and as such, have been marginalized in development, a rocket-science afterthought. The EMU was developed in the1970s as a contingency EVA suit, just in case EVA became necessary on a space shuttle mission. Specifically, NASA did not increase operating pressure, the or the differential pressure the suit operates at, because of the significant development costs. It is now clear that EVA was a critical part of almost every mission, most especially the construction and utilization of the International Space Station. The low operating pressures in the EMU have resulted in hundreds of hours of pre-breathing penalties for astronauts, costing NASA untold amounts in lost efficiency. At an ideal operating pressure of 8 pounds per square inch, astronauts would not be required to pre-breathe to purge their bloodstream of nitrogen.

NASA did not develop the IVA suits specifically for the space shuttle, either. Instead, these were modified versions of 1960s-era U2 aircraft high-altitude suits, integrated only after 1987 into the pre-existing shuttle architectures. NASA took this route even though IVAs were the mandatory launch and re-entry garments for every astronaut on the space shuttle. The contingency story continues today, with a modified version of the ACES bound for NASA's future Space Launch System (SLS).

The United States, Russia and China — the three "organizations" to send humans to space — use IVA space suits for their flights. The United States and Russia also tried flying without IVA suits for a while, only to decide that such suits were a mandatory element of safe human spaceflight. The Russians originally flew the Soyuz spacecraft without the Sokol IVA suit. Only after the 1971 Soyuz 11/ Salyut 1 mission, when a tragic loss of cabin pressure at an altitude of 43.5 miles (70 kilometers) killed three cosmonauts, did Russia redesign the Soyuz to include Sokol suits. The Sokol IVA suits fly, to this day, on the Soyuz.

NASA originally flew the space shuttle with custom flight suits, but astronauts had no emergency pressurization systems for altitudes above approximately 50,000 feet (15,000 m) — in other words, no space suits. After the Challenger tragedy, NASA reconsidered the risks to astronauts and integrated the ACES IVA suit into the space shuttle, giving astronauts an emergency pressure system in case of vehicle depress. Even the U.S. military requires pressure suits for high-altitude flights.

Suiting up for commercial space

While the revolution in commercial spaceflight is happening now in the realm of rocketry and vehicle design, it is also happening in life-support systems, training and operations — and yes, in spacesuits. Simberg and others would argue that the beginnings of any industry come with great risk to human life, and that standardized rules for safety would crush the new industry. I, for one, am sure that is not the case. Rather, regulatory standards like pressure garments (space suits) for human spaceflight would increase knowledgeable consumer confidence, drive innovation and reduce costs, and only add to the experience of the consumer. What space tourist wouldn't want to wear a spacesuit? What commercial company wouldn't want to include these safety measures for its crew, let alone its high-net-worth customers? Current commercial IVA space suit designs like ours market for less than half the cost of NASA's ACES suit, while putting a premium on safety, aesthetic, user comfort and reliability.

Beyond IVA suits for the current commercial market, there is a clear need for less expensive, less complex and more functional EVA suits for both NASA and the commercial space industry. Companies like Golden Spike and Mars One should be eager to explore EVA suit options that do not eat up significant portions of their budgets, but that still allow for real exploration and advancement. Even NASA is now considering looking beyond its traditional space suit providers for the EVA suits of the future.

Introducing competition to this traditionally closed industry is sure to further reduce costs and improve functionality. The same technologies that allow commercial launch providers to build and test rockets at a fraction of the cost to governments permit companies like mine to build and test space suits at a fraction of the cost for traditional providers. Spacesuits no longer have to be fantastically expensive clothes. Innovations like this, I maintain, will not crush the new industry; they will protect and bolster it.

I am excited to compete in this dawning of a new age of space exploration. I am proud to be working on garments that could affect the very comfort and functionality of future astronauts. And I am hopeful for the near future, when the safety and well-being of the user is considered supreme, with logical and limited regulations in place to protect both the astronaut and the industry, and fair and open competition between various service and hardware providers.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.