After 2 Years on Mars, NASA's Curiosity Rover Aims for Huge Mountain

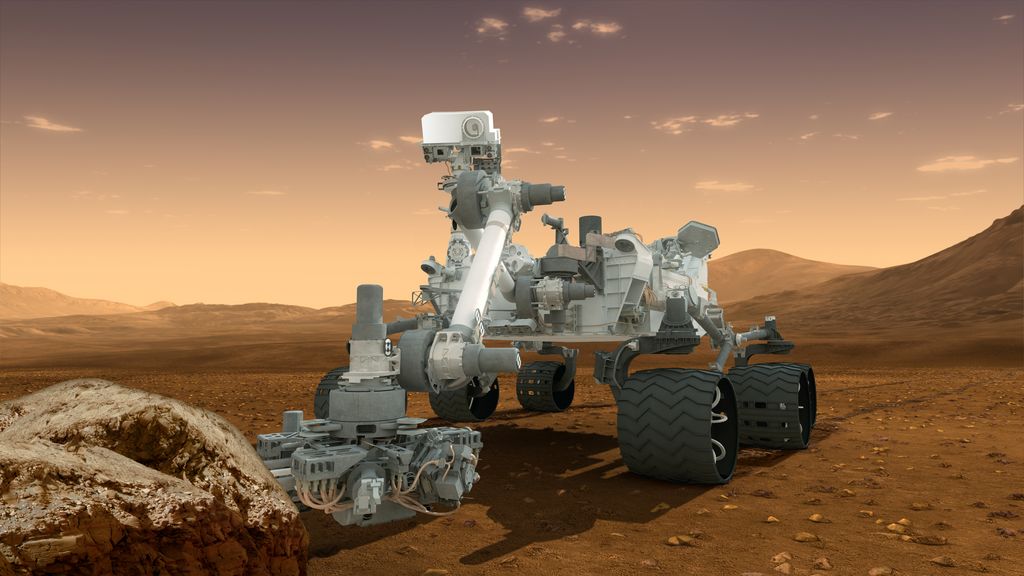

Two years ago this week, much of the world held its breath as a rocket-powered sky crane lowered NASA's huge Curiosity rover to the surface of Mars on cables.

The bold and unprecedented maneuver worked on the night of Aug. 5, 2012, eliciting high fives and raucous cheers at mission control at the space agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, as well as at viewing parties around the globe.

Curiosity has ridden this wave of enthusiasm for two years now. The rover made landmark discoveries in its first few months of operation, helping reshape scientists' understanding of Mars while barely straying from its landing site inside the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater. [Mars Rover Curiosity's Latest Amazing Photos]

And mission team members are excited about what the future may hold, as Curiosity gets closer and closer to its ultimate science destination — the foothills of a 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) mountain called Mount Sharp.

Habitable Mars

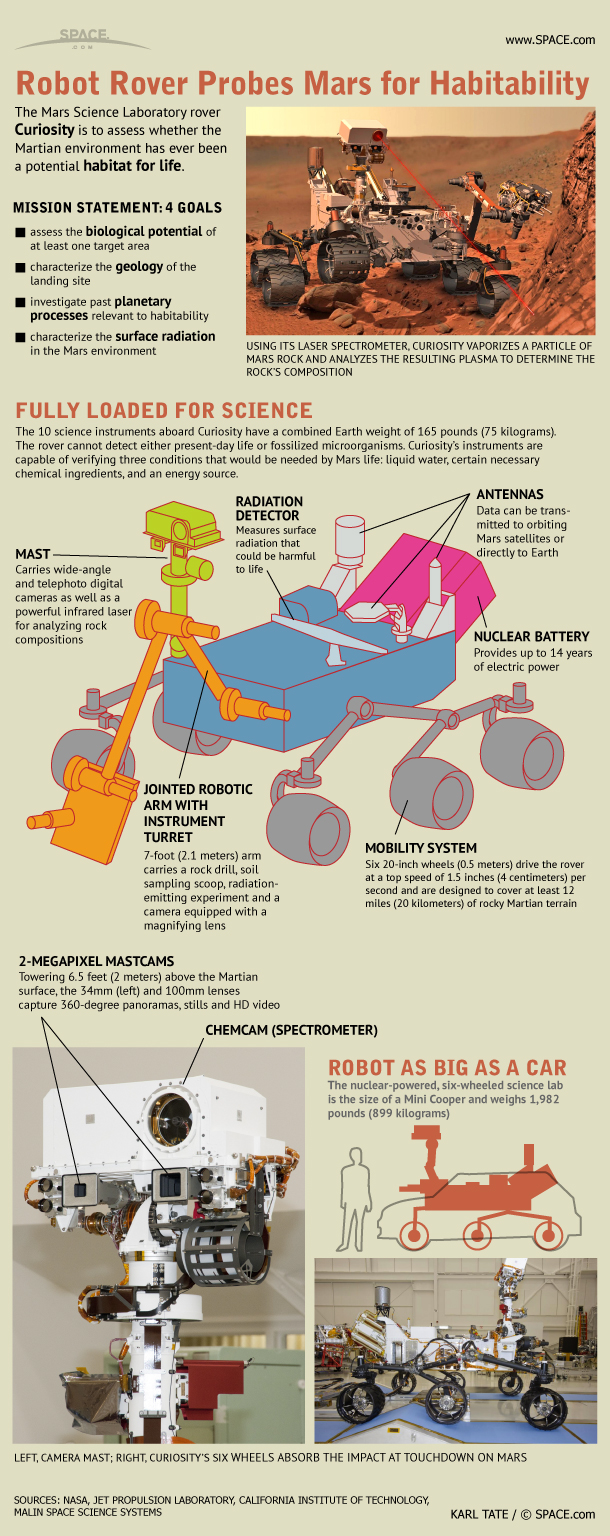

The main goal of Curiosity's $2.5 billion mission is to determine if Mars has ever been able to support microbial life.

The rover found some hints pointing toward past habitability in September 2012, when it rolled through an ancient streambed that mission scientists say probably flowed continuously for more than 1,000 years long ago. And Curiosity sealed the deal a few months later after drilling into rocks at a site called Yellowknife Bay.

Analysis of the drilled samples revealed that Yellowknife Bay was inded a habitable environment billions of years ago, likely featuring water benign enough to drink, mission team members said. Further study suggested the area was a lake-and-stream system that may have been able to support simple lifeforms for millions of years at a time. (Curiosity has not actually found signs of life; it was not designed to do such work.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Making such big discoveries so soon was a bit of a surprise, the rover's handlers said.

"Scientifically, Gale Crater, and especially the plains around Mount Sharp, have exceeded any of our expectations," Curiosity deputy project scientist Ashwin Vasavada of JPL told Space.com. "The place was just covered by water on and off again through its history. That's something we never anticipated based on the information we only had from orbit, before landing."

Rough road

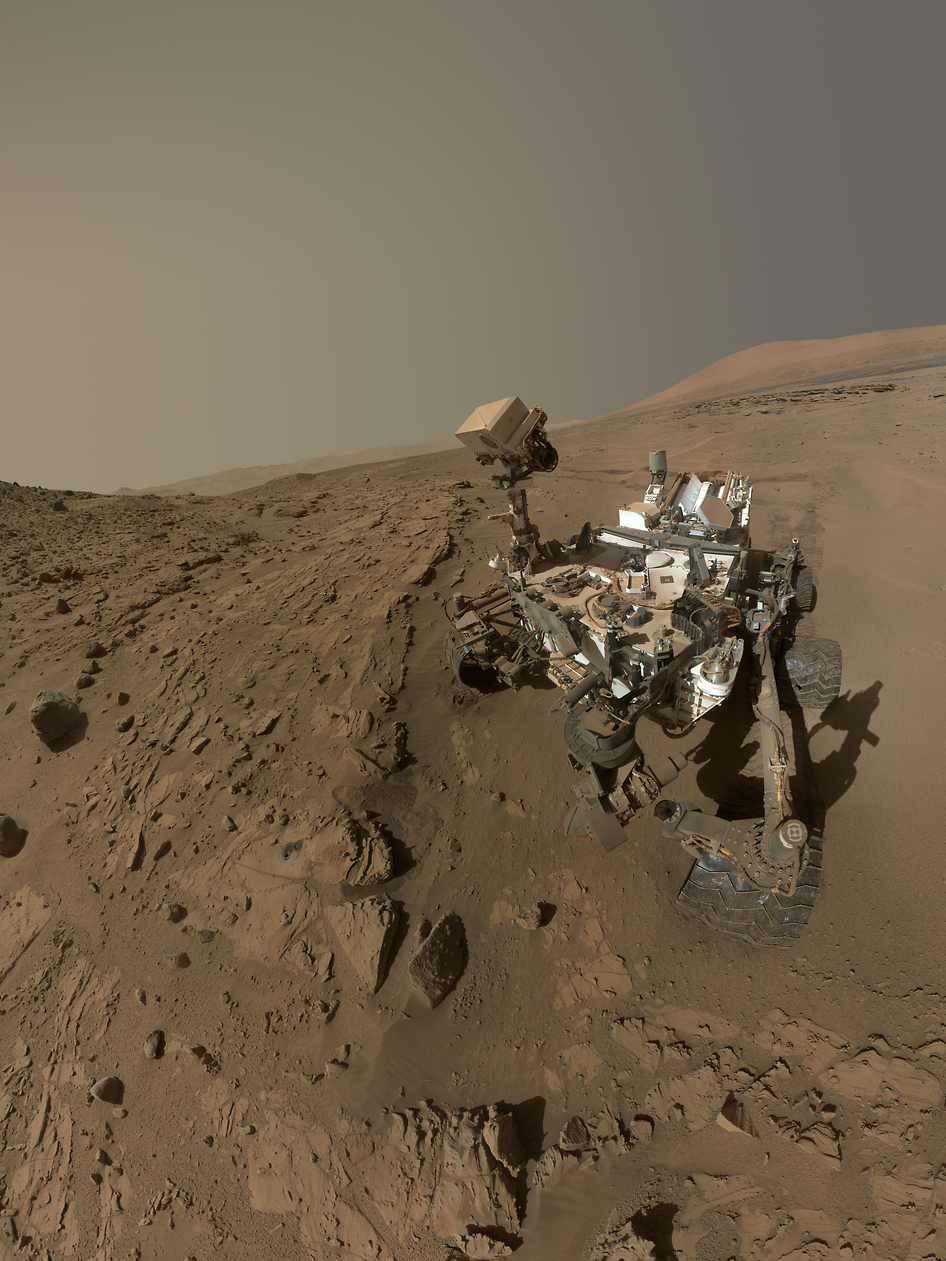

There have been some unpleasant surprises as well, however. The rough terrain inside Gale Crater has taken a toll on Curiosity's wheels, which late last year began accumulating nicks and dings at a worrying rate.

"It started out to be very concerning, to the point where we really just shut down operations for a few weeks to kind of catch our breath and understand what was going on," Vasavada said.

But after spending a few months studying the Red Planet terrain, performing simulated drives at JPL's "Mars Yard" and practicing different driving techniques with Curiosity — driving backward sometimes, for example — the rover's operators think they have things under control now.

"It is a problem, but it's something we can manage, and make it through our mission exactly how we wanted to make it," Vasavada said.

Looking ahead to Mount Sharp

While the Curiosity rover was pretty sedentary during its first year on Mars, it has been making serious tracks in year number two.

The robot has driven a total of about 5.6 miles (9 km) since touching down on the Red Planet, and about 5 of those miles have come since it departed Yellowknife Bay for Mount Sharp in July 2013, Vasavada said. The target location at the mountain's base still lies 2 to 2.5 miles away (3 to 4 km), and the mission team expects to get there by the end of 2014, he added.

The plan calls for Curiosity to climb up through the mountain's foothills, which likely preserve a record of the Red Planet's transition from a relatively warm and wet place in the ancient past to the cold, dry world it is today.

"The hope is that we can traverse those rock layers and read Mars like a history book, going from the earliest time period where we see some evidence for clays from orbit, to sulfates, to this dusty layer on top where it might represent the modern conditions," Vasavada said.

"What we can do is place this one habitable environment that probably represents a snapshot of time into the context of all that history exposed at Mount Sharp," he added. "We can also look at whether there were time periods before, or after — multiple time periods that were also habitable environments."

Curiosity doesn't have to summit Mount Sharp to get a good read on Martian history. Mission scientists want the rover to make it up at least to the sulfate layers, which apparently begin at about 1,300 to 1,640 feet (400 to 500 meters) up the mountain.

"Not to imply that 500 meters is going to be easy — that's a good amount of elevation — but it looks doable from what we're able to map from orbit," Vasavada said.

Welcoming NASA's next Mars rover?

NASA plans to launch a Mars rover based heavily on Curiosity in 2020. The 2020 rover, whose suite of science instruments was announced last week, will search for signs of past life, cache samples for possible future return to Earth and produce oxygen from the Red Planet's carbon-dioxide-rich atmosphere, among other activities. [NASA's 2020 Mars Rover in Pictures]

It's possible that Curiosity could still be operating when the 2020 rover touches down, Vasavada said. But if that's the case, Curiosity would likely be performing only limited science work, since its radioisotope thermoelectric generator — which converts the heat from plutonium-238's radioactive decay to electricity — will be pretty low on fuel.

Curiosity is different in this respect from NASA's Mars rover Opportunity, which is still going strong more than 10 years after landing on the Red Planet. Opportunity is solar-powered and can conceivably continue to operate as long as its solar panels remain relatively dust-free.

"Our best years are going to be the next two to four years, because it's a confluence of getting to our primary science target and still having a juicy power generator," Vasavada said. "We would love to welcome 2020 to Mars, but [Curiosity] will probably be in the retirement home by then."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.