How Our Milky Way Galaxy Got Its Spiral Arms

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

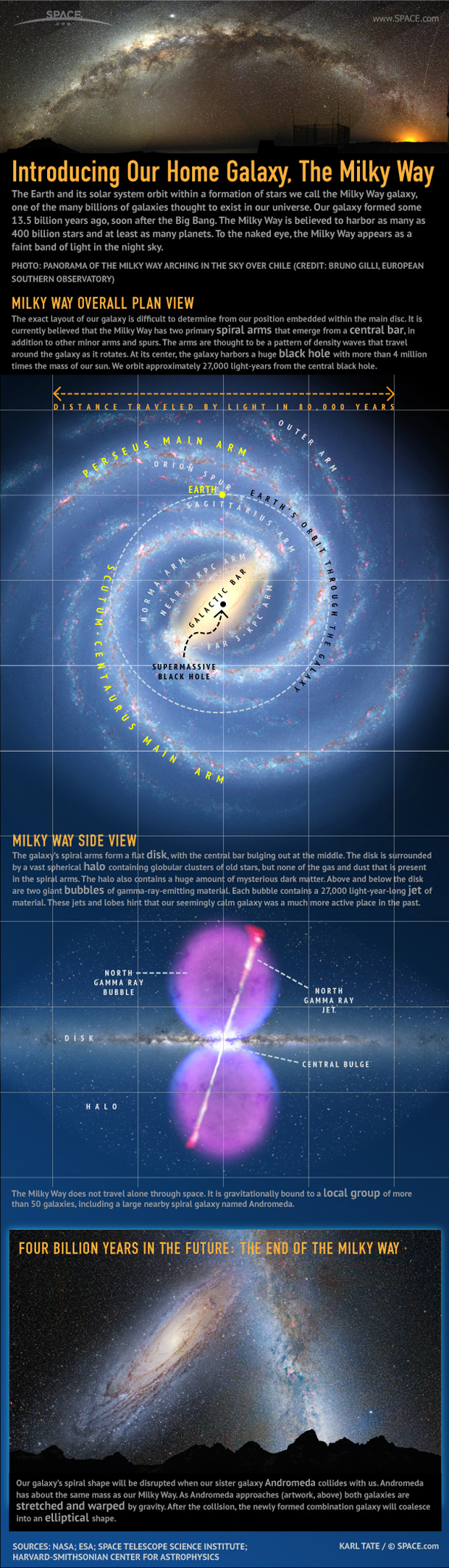

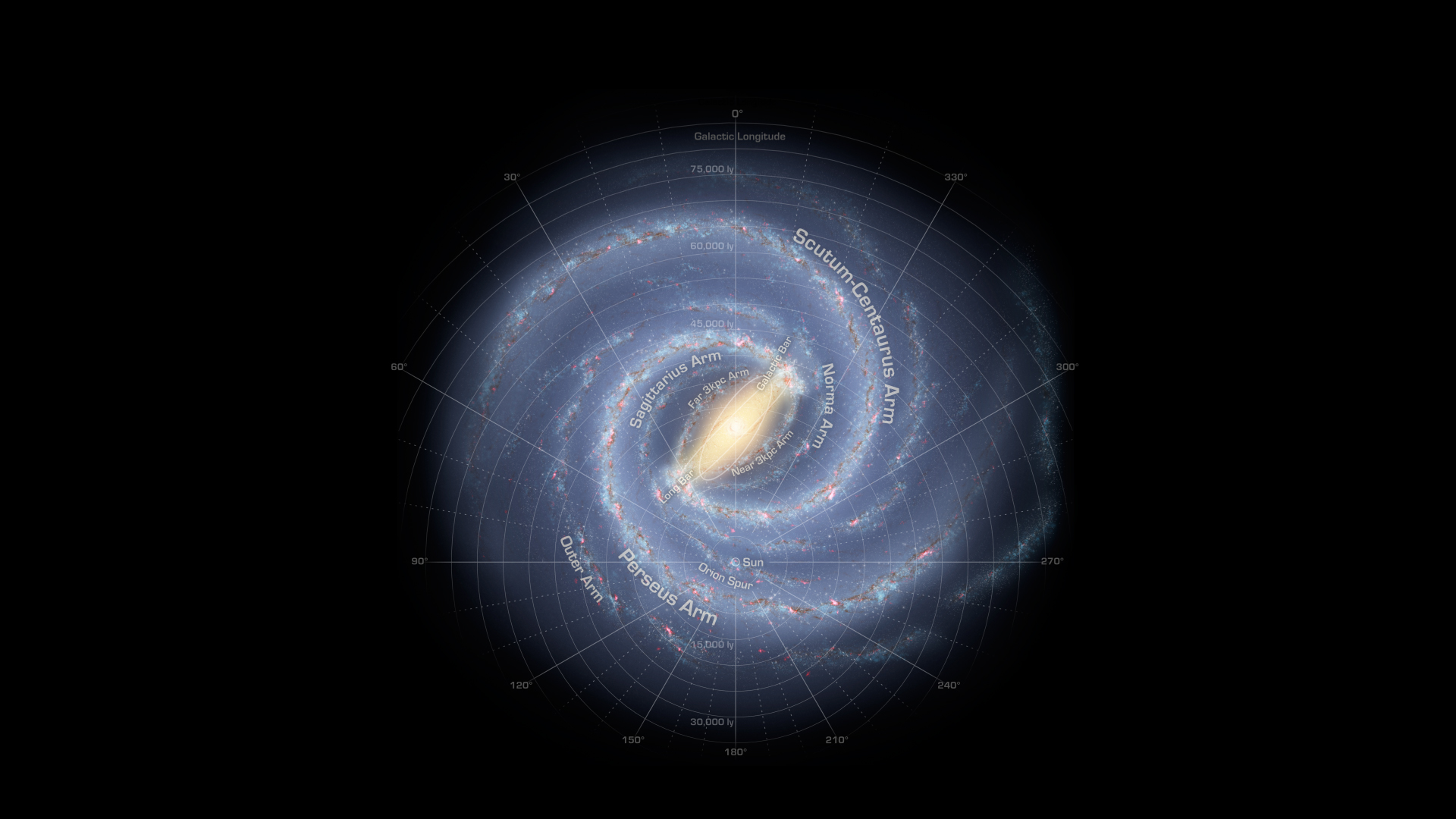

The shape of the Milky Way galaxy, our solar system's home, may look a bit like a snail, but spiral galaxies haven't always had this structure, scientists say.

In a recent report, a team of researchers said they now know when and how the majestic swirls of spiral galaxies emerged in the unicerse. Galaxies are categorized into three main types, based on their shapes: spiral, elliptical and irregular. Almost 70 percent of those closest to the Milky Way are spirals. But in the early universe, spiral galaxies didn't exist.

A husband and wife team of astronomers, Debra Meloy Elmegreen at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and Bruce Elmegreen at IBM's T.J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., analyzed an image from the Hubble Space Telescope known as the Ultra Deep Field. It was taken over a four-month period in late 2003 and early 2004. The picture shows about 10,000 galaxies of different ages, some nearly as old as the universe itself. [Galaxies of the Universe Explained by Type (Infographic)]

To analyze this image, the researchers first sorted the galaxies into several basic types, "such as disk-like, clumpy, elliptical, tadpole-shape and double," said Debra Elmegreen. "We did this for all of the galaxies larger than 10 pixels in diameter, which we thought were large enough to classify, [which came to] about 1000 galaxies."

The scientists then used these classifications to study the most peculiar type of galaxy, a "very clumpy" type that does not really occur anymore in the current universe. However, the researchers established that most young galaxies were born very clumpy, because of gravitational instabilities in a highly turbulent, gas-rich disk.

Then, the Elmegreens studied the Hubble Ultra Deep Field for a second time, now examining the tadpole-shaped galaxies. Finally, they analyzed the spirals. "The motivation for this was the 50th anniversary of the publication of a very important paper on spiral density waves in galaxies, the paper by C.C. Lin, and Frank H. Shu, 'On the Spiral Structure of Disk Galaxies,' which appeared in 1964 in the Astrophysical Journal," said Bruce Elmegreen.

A chaotic place

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Out of 269 spiral galaxies in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, the researchers analyzed 41. They discarded galaxies when it was impossible to determine a clear spiral structure or when there wasn't enough data to establish the galaxy's age. The researchers then sorted these 41 spiral galaxies into five different types, according to whether they were clumpy or smooth, well-defined or not, and the number and clarity of spiral arms they had. Next, the Elmegreens catalogued the properties of each galaxy type, such as its age, the size of clumps inside and its brightness at various frequencies.

The researchers found that the universe was a very chaotic place in its infancy. The first galaxies were disks with massive, bright, star-forming clumps and little regular structure. To develop the nice spiral forms seen today, galaxies first had to settle down, or "cool," from the previous chaotic phase. This evolution took several billion years.

Gradually, the galaxies that were to become spirals lost most of their big clumps, and a central, bright bulge would appear; the smaller clumps throughout the galaxy would begin to form indistinct, "woolly" spiral arms.

These arms would only become very distinct arms once the universe was about 3.6 billion years old. At that age, as the galaxies had a chance to settle down, the turbulence decreased, and new stars would form in a much quieter disk. "We can see the transition from the early chaotic state to the modern, relaxed state," said Bruce Elmegreen.

These first spiral galaxies were either two-armed structures or had thick, irregular spirals with some remaining clumps. More finely structured, multi-armed galaxies like the Milky Way galaxy and its neighbor Andromeda appeared much later, when the universe was 8 billion years old.

Next, the researchers plan to analyze other surveys, to get a broader picture of galaxies as a whole, including their overall masses, general morphologies and distribution in space. "We are interested in the internal structures of these galaxies, including star formation structures and spiral arm structures," said Bruce Elmegreen. [See amazing photos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope]

"Studies of these internal structures require the highest possible angular resolution and depth of exposure, and so far it is difficult to compete with the Advanced Camera for Survey images of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field," he added. "In the future, we would like to try to extend our analysis to other fields so that we can include more galaxies, to the extent that it is possible."

Kartik Sheth, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Va., who was not involved in the study, called the research "another useful piece of information in understanding the detailed assembly of [galactic] disks."

However, he added, the results had certain limitations. "We assume that the same criteria we apply for measuring and understanding stellar structures locally is also applicable in the distant past," Sheth said.

"This is OK, but imagine that if we are looking for butterflies, and galaxies were cocoons at an earlier time," he said. "We would get an incorrect result. So care has to be taken in understanding selection effects."

Still, Sheth said, the research is "pretty interesting and important." And once Hubble's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, launches, "we will really be able to nail all this, because we will have the same resolution at the longer wavelengths as we now have with Hubble in the optical."

Follow Katia Moskvitch on Twitter @SciTech_Cat. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Katia Moskvitch is a freelance science writer based in Switzerland currently serving as the head of communications for IBM Switzerland. She an award-winning writer who has covered astrophysics and other topics for Space.com, with her work also appearing in Quanta Magazine, Science, Wired, BBC News, Scientific American and The Economist among others.

In 2019, Katia was named European Science Journalist of the Year as well as British Science Journalist of the Year, and her book "Neutron Stars: The Quest to Understand the Zombies of the Cosmos" was published by Harvard University Press in September 2020. Katia holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from McGill University and master's degrees in journalism from the University of Western Ontario and in theoretical physics from King's College in London. She is fluent in English, French and Russian.