Moon Surprise: Lunar Craters Are Bigger on Near Side

The near side of the moon hosts larger impact basins than the satellite's far side, and the explanation lies in key differences between the two hemispheres, a new study suggests.

Scientists have long understood that craters form at an even rate on the surfaces of both sides of the moon, but new work reports that ancient asteroid impacts on the near side of the moon produced larger basins than those on the far side.

The surprising difference hinges upon the composition of the crust on the two sides of the moon. The near side, which always faces Earth, was warm during the early formation of the moon and subjected to volcanic activity. This might have created an ideal environment for big craters to form, scientists said. [10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

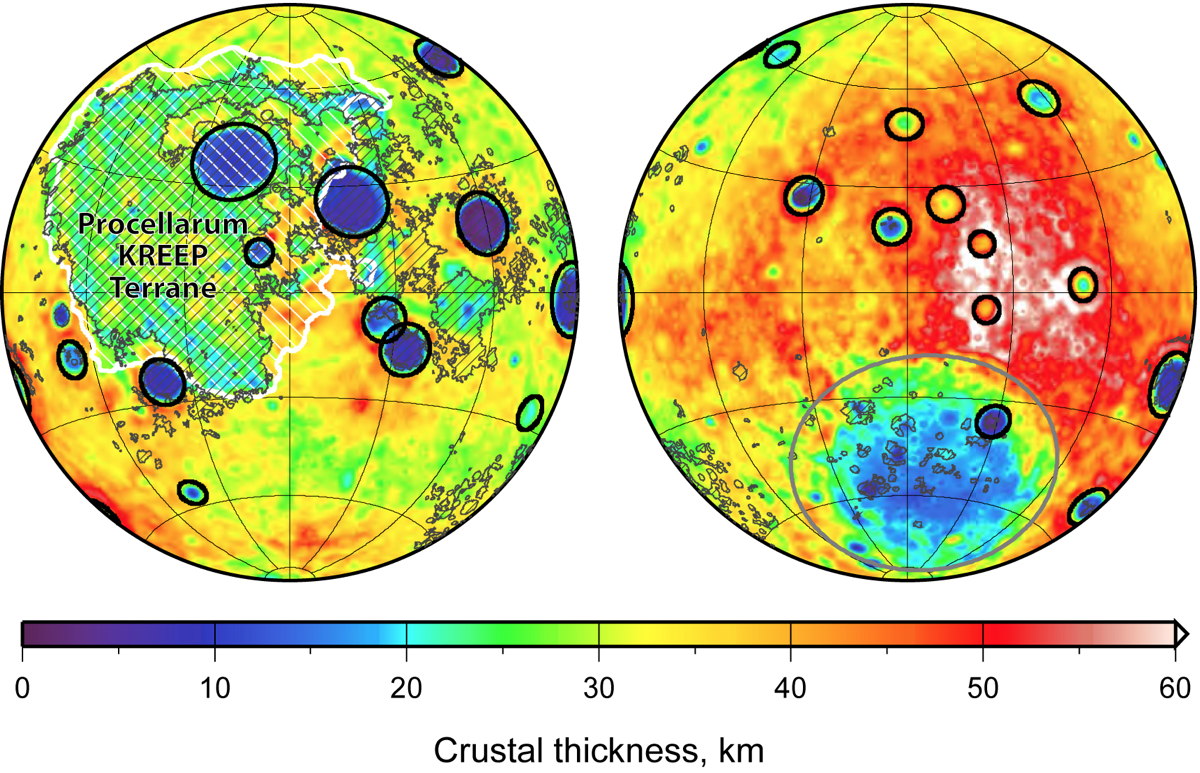

"When we look at the maps of both hemispheres, we realize there are more big basins on the near side than on the far side," said Katarina Miljkovic of the Institute de Physique du Globe de Paris, lead author of the new moon study published in the Nov. 8 issue of the journal Science. "There are eight of them on the near side that are bigger than 300 kilometers [186 miles]… and only one on the far side."

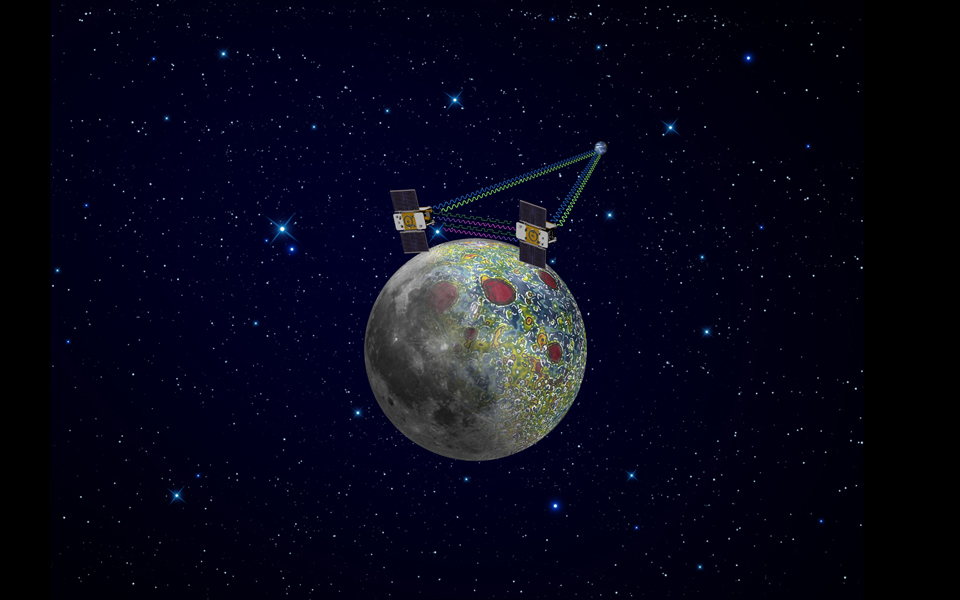

Using data gathered by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) spacecraft, Miljkovic and her colleagues ran computer simulations to model the effects of long-ago impacts on the moon's crust. They found that an impact on the near, hotter side of the moon would form a crater about two times larger than craters formed by a similarly sized asteroid on the cold, far side of the moon.

The near side's hot crust didn't fall back into itself when struck like the cold, stiff crust of the far side. Instead, the malleable surface of the near side was able to expand, creating larger basins and displacing more of the crust, even if the impactor was not necessarily huge, Miljkovic found.

The new work could have implications for scientists' understanding of the solar system's early days, researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists have long thought that huge numbers of comets and asteroids impacted Earth, the moon and other bodies in the inner solar system from about 3.8 billion to 4.1 billion years ago. In light of this new work, however, ideas about that period, known as the "late heavy bombardment," might need to be altered, Miljkovic said.

The mass of space rocks hurling toward Earth and the moon during the late heavy bombardment period may be overestimated, Miljkovic said.

"These big basins on the near side appear larger than they should," Miljkovic told SPACE.com. "If we only rely on the near side basins to give us information about the late heavy bombardment for impact flux, then it is possible that it is likely overestimated."

Much of the information scientists have gleaned about the late heavy bombardment comes from moon craters, so if the large basins formed differently than originally thought, it might necessitate a change in the way researchers understand the history of the solar system, said Noah Petro, a research scientist working with NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission.

"All of the understanding of impacts goes back to the moon," Petro, who is unaffiliated with the new study, told SPACE.com. "Until we really understand what happened on the moon, it's difficult to apply it to other bodies. There have been lines of evidence drawn from other bodies, but ultimately it cycles back to our understanding of what happened on the moon."

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.