James Webb Space Telescope finds an 'extreme' glow coming from 90% of the universe's earliest galaxies

The universe's early galaxies are way brighter than they should be. The James Webb Space Telescope's discovery of brightly glowing gas around 90% of primordial galaxies may explain why.

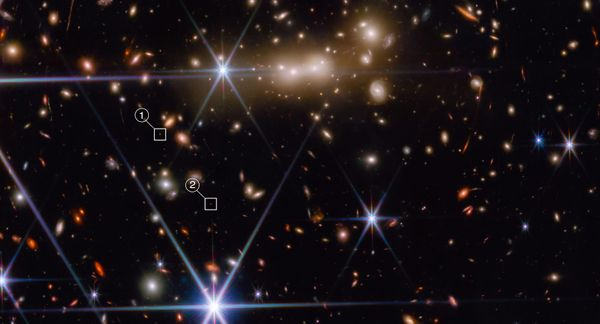

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has discovered that nearly all of the universe's earliest galaxies were filled with dazzling gas clouds that blazed brighter than the emerging stars within them — and it could help solve a mystery that threatens to break cosmology.

Forming as early as 500 million years after the Big Bang, some early galaxies have been seen glowing so brightly that they shouldn't exist: Brightnesses of their magnitude should come only from massive galaxies with as many stars as the Milky Way, yet the galaxies took shape in a fraction of the time our galaxy took to form.

The discovery threatened to upend physicists' understanding of galaxy formation and even the standard model of cosmology, which states that a few million years after the Big Bang (13.8 billion years ago) energy condensed into matter from which the first stars slowly coalesced. Yet when the JWST came online, it saw far too many stars.

Related: James Webb telescope detects alien planet with clouds made of quartz

Now, astronomers have found a possible answer: a large group of 12 billion-year-old galaxies almost 90% of which were wreathed in bright gas that — after being ignited by light from the surrounding stars — triggered intense bursts of star formation as the gas cooled. The new research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

"Our paper proves that interactions with the neighboring galaxies are responsible for the unusual brightness of early galaxies," lead author Anshu Gupta, an astrophysicist at Curtin University in Australia, told Live Science in an email. "The explosion of star formation triggered by the interactions could also explain the more massive nature of early galaxies."

Astronomers discovered the bright gas clouds in data collected as part of JWST's Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, which used three of the telescope's instruments to collect infrared images of galaxies before analyzing their spectra.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By peering at the frequencies of light the galaxies emitted, the researchers discovered spikes of "extreme emission features" — a clear sign that the gas was capturing light from nearby stars before reemitting it.

"Gas cannot emit light on its own," Gupta said. "But the young, massive stars emit just the right type of radiation to excite the gas — and the early galaxies have lots of young stars."

After comparing this emission spectrum with those found in newer galaxies populating today's universe, the researchers found that around 1% had similar features. The researchers said that by studying these later galaxies, which are easier to measure, they will gain important insight into the earlier galaxies and the beginnings of the universe's chemistry.

"The chemical elements that make up everything tangible on Earth and the universe, except hydrogen and helium, originated in the cores of distant stars," Gupta said. "So, it is critical to understand the conditions surrounding galaxies and stars in the early universe for us to better understand our own world today."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like weird animals and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.