Effects of Ancient Meteor Impacts Still Visible on Earth Today

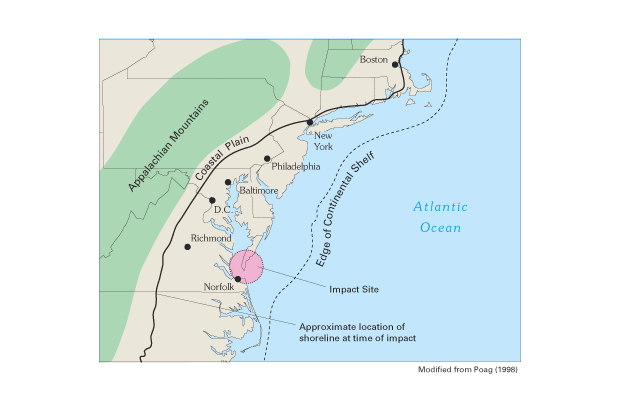

More than 35 million years ago, a 15-story wall of water triggered by an asteroid strike washed over Virginia from its coast, then located at Richmond, to the foot of the inland Blue Ridge Mountains — an impact that would affect millions of people should it occur today. Yet despite its age, the effects of this ancient asteroid strike, as well as other epic space rock impact scars, can still be felt today, scientists say.

The Virginia impact site, called the Chesapeake Bay Crater, is the largest known impact site in the United States and the sixth largest in the world, said Gerald Johnson, professor emeritus of geology at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. Despite its size, clues about the crater weren't found until 1983, when a layer of fused glass beads indicating an impact were recovered as part of a core sample. The site itself wasn't found until nearly a decade later. [When Space Attacks: The 6 Craziest Impacts]

The comet or asteroid that caused the impact, and likely measured 5 to 8 miles (8 to 13 kilometers) in diameter, hurtled through the air toward the area that is now Washington, D.C., when it fell. The impact crated a massive wave 1,500 feet (457 meters) high, researchers said.

Though the impactor left a crater about 52 miles across and 1.2 miles deep (84 km across and 1.9 km deep), the object itself vaporized, Johnson explained.

"I'm just sad we can't have a piece of it," Johnson said in a statement.

Modern effects

But the effects of the asteroid impact can still be seen today, most notably in the bay itself. Until 18,000 years ago, the bay region was dry. A giant ice sheet then covered North America, and when it began melting 10,000 years ago, valleys flooded, including the depression formed by the crater.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The ancient impact still affects the region today, in the form of land subsidence, river diversion, disruption of coastal aquifers and ground instability.

Last February, an meteor explosion over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk confirmed that the Chesapeake Bay impactor wasn't the only space rock out there aimed at Earth. Though the Chelyabinsk asteroid was only about 56 feet (17 m) in diameter, it injured more than 1,000 people and caused millions of dollars in structural damage.

"That asteroid still had a major effect on the ground, and there are potentially millions of them," Dan Mazanek, a near-Earth object (NEO) expert at NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia, said in the statement. "Another meteor of similar size to that would be the next likely event."

Finding NEOs

Every day, small objects pass near Earth or burn up in the planet's atmosphere. Objects about 50 miles (80 km) across pass within a few lunar distances on a monthly or annual basis without being drawn in by the planet's gravity.

"The frequency is always a question," Mazanek said. "We know that the larger objects are less frequent, but they have more devastating effects."

According to models, scientists have discovered only about 10 percent of the objects larger than 328 feet (100 m), leaving many potentially threatening asteroids that pose a threat to the Earth still unknown.

Both telescope and radar are instrumental in searching for incoming objects. NASA's Near-Earth Object Program is one of the groups watching for potentially dangerous incoming objects. Mazanek said the program has been responsible for about 99 percent of all NEO discoveries since 1998.

Knowing where to point the instruments is a challenge. Timing, too, is tricky. A 100-year impact event doesn't mean that 100 years will pass before the event occurs again.

"It's not like a bus or a train schedule; it just happens that frequently on average," Mazanek said. "It's like a coin toss. Even though it's a 50-50 heads or tails average, it could be heads 10 times in a row or tails 10 times in a row."

Follow SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky