Like Moths to a Flame, Alien Planets Can Flock to Nearest Star

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

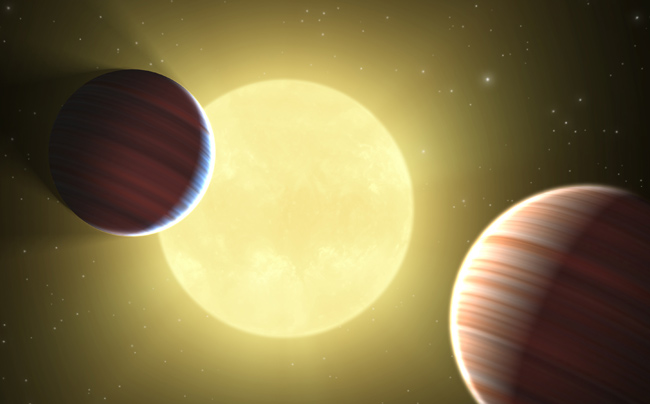

A newfoundalien solar system with planets the size of Saturn circling close to their staris helping astronomers learn how some giant worlds snuggle up to their stellarparents like moths to a flame.

NASA'sKepler space observatory recently confirmed the presence of the two Saturn-sized planets that orbit a star about 2,300 light-years away fromEarth. A third, much smaller planet may also orbit the star, circling so closethat one year on the alien world would last just 1.6 Earth days.

Whilethe discovery of the Kepler-9 planetary system is a major find, it is also astarting point for astronomers to learn how the planet arrangement formed inthe first place. [Gallery - Strangest Alien Planets]

Scientiststhink these planets originated much farther from their parent star and graduallymigrated inward over time. All three objects could fit inside the orbit ofMercury today.

"It'ssafe to say that they did migrate because they ended up in this very specialset of orbits," said Alycia Weinberger, an astronomer in the department ofterrestrial magnetism at the Carnegie Institution of Washington in Washington,D.C., when the planets were announced in late August."

"The likelycandidate for how that migration happened is interaction between these planetsand the original disk of material ? the gas out of which they formed. It willnow take some work to try to figure out exactly how that was likely to happenin this system," Weinberger said.

Timingplanet paths

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Understandingthe process of planetary migration will help astronomers understand the initialconditions that led to the final configuration of the Kepler-9 system, andother planetary systems discovered in the future.

Asa planetary system is being formed, "planets can change locations ormigrate due to interactions with the raw materials with which they arebuilt," Weinberger said.

Astudy led by Matthew Holman, associate director of the theoretical astrophysicsdivision at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.,determined that the two Saturn-sized planets, named Kepler-9b and Kepler-9c,have somewhat atypical orbits.

Ittakes Kepler-9b about 19.2 days to complete one orbit. The other Saturn-sizedworld, Kepler-9c, makes one orbit every 38.9 days, taking almost twice as longto complete the circuit.

"Thereis a near 2-to-1 orbital resonance, which means the planets have orbitalperiods in a 2-to-1 ratio," Holman told SPACE.com. "At thisconfiguration, we can see that they strongly interact and we can see largevariations in the orbits of the planets."

Whatplanetary migration tells us

Studyinghow planetary migration occurs, and how much a planet has moved, can tellresearchers a lot about the history of how such worlds and their local solar systemformed.

Kepler-9band 9c were found to have a lot of gravitational interaction, and they arelocated so close to their parent star that their orbits would fit inside theorbit of Mercury in our own solar system, said Holman.?

Thetwo planets most likely migrated to their observed locations, said Weinberger, becausebeing so close to the star would have made it extremely difficult to developand survive in the first place.

Observationscombined with theoretical work will then be able to pinpoint how far apart theplanets originated, how long it took them to form and how long their migrationlasted.

"Keplerwas designed and built to answer fundamental questions," Weinberger said."We want to know what types of planetary systems there are; what is commonamongst the various systems; whether there are any special conditions thatresult in Earth-like planets; whether the whole system of planet formation is robust andcommon."

- 5 Intriguing Earth-Sized Planets

- Gallery - Strangest Alien Planets

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.