Oceans on Ancient Venus, Study Suggests

Venus mayonce have been more Earth-like, with volcanic activity and an ocean of water, anew map of the toasty planet's southern hemisphere suggests.

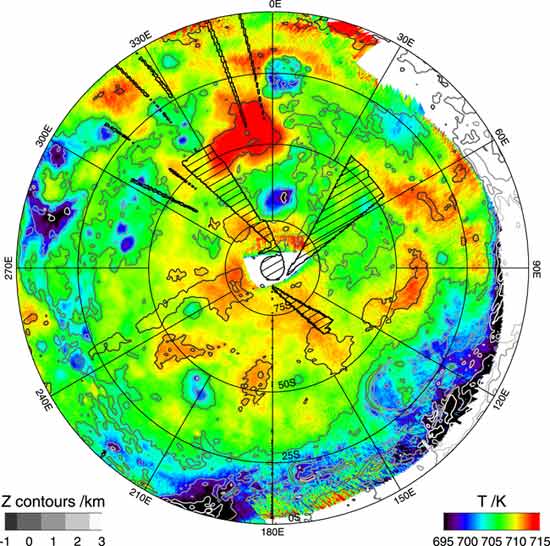

The mapcomprises over a thousand individual images, recorded between May 2006 andDecember 2007 by the European Space Agency's VenusExpress spacecraft. It gives astronomers another tool in their quest to understandwhy Venus is so similar in size to Earth and yet has evolvedso differently.

Because Venusis coveredin clouds, normal cameras cannot see the surface, but Venus Express used aparticular infrared wavelength to see through them.

Althoughradar systems have been used in the past to provide high-resolution maps ofVenus?s surface, Venus Express is the first orbiting spacecraft to produce amap that hints at the chemical composition of the rocks.

Rockyclues

The new datais consistent with suspicions that the highland plateaus of Venus are ancientcontinents, once surrounded by ocean that might have evaporated away into spaceand produced by past volcanic activity.

"Thisis not proof, but it is consistent. All we can really say at the moment is thatthe plateau rocks look different from elsewhere," said Nils M?ller of thethe University M?nster and DLR Berlin, who headed the mapping efforts.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Water is akey to life as we know it. And though there are no signs of past or presentbiology on the suffocating surface Venus, someastronomers have speculated that the its cloudscould harbor life.

The rockslook different because of the amount of infrared light they radiate into space.Different surfaces radiate different amounts of heat at infrared wavelengthsdue to a material characteristic known as emissivity, which varies in differentmaterials.

The eightRussian landers of the 1970s and 1980s touched down away from the highlands andfound only basalt-like rock beneath their landing pads.

The new mapshows that the rocks on the Phoebe and Alpha Regio plateaus are lighter in colorand look old compared to the majority of the planet. On Earth, suchlight-colored rocks are usually granite and form continents.

Granite isformed when ancient rocks, made of basalt, are driven down into the planet byshifting continents, a process known as plate tectonics. The water combineswith the basalt to form granite and the mixture is reborn through volcaniceruptions.

"Ifthere is granite on Venus, there must have been an ocean and plate tectonics inthe past," M?ller said.

Let's gosee

M?llerpoints out that the only way to know for sure whether the highland plateaus arecontinents is to send a lander there.

Over time, Venus?swaterhas been lost to space, but there might still be volcanic activity. Theinfrared observations are very sensitive to temperature. But in all images theysaw only variations of between 3-20?C, instead of the kind of temperaturedifference they would expect from active lava flows.

Still, M?llerdoes not rule out the existence of volcanic activity on present-day Venus.

"Venusis a big planet, being heated by radioactive elements in its interior. Itshould have as much volcanic activity as Earth," he said. Some areas doappear to be composed of darker rock, which hints at relatively recent volcanicflows.

Scientistsalso debate whether past or present volcanic activity is the sourceof the sulfur dioxide clogging Venus' atmosphere.

- Venus Glows in Invisible Light

- Images: Below the Clouds of Venus

- Venus and Earth: Worlds Apart

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.