Major Breakthrough: First Photos of Planets Around Other Stars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomershave taken what they say are the first-ever direct images of planets outside ofour solar system, including a visible-light snapshot of a single-planet systemand an infrared picture of a multiple-planet system.

Earth-likeworlds might also exist in the three-planet system, but if so they are too dimto photograph. The other newfound planet orbitsa star called Fomalhaut, which is visible without the aid of a telescope.It is the 18th brightest star in the sky.

The massiveworlds, each much heftierthan Jupiter (at least for the three-planet system), could change how astronomers define the term ?planet,? oneplanet-hunter said.

Article continues belowBreakthroughtechnology

Until now,scientists have inferred the presence of planets mainly by detecting an unseenworld's gravitational tug on its host star or waiting for the planet to transitin front of its star and then detecting a dip in the star's light. While thesemethods have helped to identify more than 300 extrasolar planets to date,astronomers have struggled to actually directly image and see such inferred planets.

The fourphotographed exoplanets are discussed in two research papers published onlinetoday by the journal Science.

"Everyextrasolar planet detected so far has been a wobble on a graph. These are thefirst pictures of an entire system," said Bruce Macintosh, anastrophysicist from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, andpart of the team that photographed the multi-planet system in infrared light."We've been trying to image planets for eight years with no luck and nowwe have pictures of three planets at once."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomershaveclaimed previously to have directly imaged a planet, with at least two suchobjects, though not everybody agreed the objects were planets. Instead, theymay be dim, failed stars known as brown dwarfs.

Multi-planetsnapshots

Macintosh,lead researcher Christian Marois of the NRC Herzberg Institute of Astrophysicsin Canada, and colleagues used the Gemini North telescope and W.M. KeckObservatory on Hawaii's Mauna Kea to obtain infrared images. Infrared radiationrepresents heat and, along with everything from radio waves to visible lightand X-rays, is part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

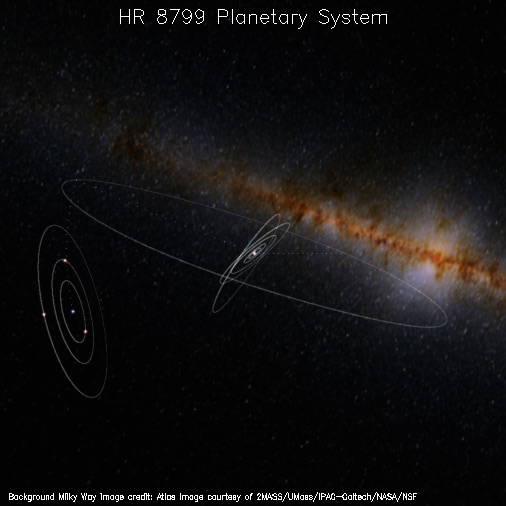

The trio ofworlds orbits a star named HR 8799, which is about 130 light-years away in theconstellation Pegasus and about 1.5 times as massive as the sun. The planetsare located at distances from their star of 24, 38 and 68 astronomical units(AU). (An astronomical unit equals the average Earth-sun distance of 93 millionmiles, or about 150 million km.) Other planet-finding techniques work out toonly about 5 AU from a star.

The planetclosest to the star weighs in at 10 times the mass of Jupiter, followed byanother 10 Jupiter-mass planet and then, farther out, a world seven times theheft of Jupiter.

Byastronomical standards, the planets are fresh out of the oven, forming about 60million years ago. That means the orbs are still glowing from heat leftoverfrom their formation. Earth, by comparison, is about 4.5 billion years old.

The mostdistant planet orbits just inside a diskof dusty debris, similar to that produced by the icy objects of the solarsystem's Kuiper belt, which lies just beyond the orbit of Neptune.

The setupof this planetary system, along with its dusty belt, suggests it is a scaled-upversion of our solar system, Macintosh said. That means other planets closer into the host star could be waiting for discovery.

"Ithink there's a very high probability that there are more planets in the systemthat we can't detect yet," Macintosh said. "One of the things thatdistinguishes this system from most of the extrasolar planets that are alreadyknown is that HR 8799 has its giant planets in the outer parts ? like our solarsystem does ? and so has 'room' for smaller terrestrial planets, far beyond ourcurrent ability to see, in the inner parts."

Hubble'sdiscovery

Universityof California, Berkeley, astronomer Paul Kalas led the team of astronomers whotook the visible-light snapshot of the single-planet system. The exoplanet hasbeen named Fomalhaut b, and is estimated to weigh no more than three Jupiter masses.

The HubbleSpace Telescope's Advanced Camera for Surveys was used to make the image. The camerais equipped with a coronagraph that blocks out the light of the host star,allowing astronomers to view a much fainter planet.

"It'skind of like if driving into the sun and suddenly you flip down your visor, youcan see the road easier," Kalas said during a telephone interview. Infact, Fomalhaut b is 1 billion times fainter than its star. "It's not easyto see. That kind of sensitivity has never been seen before," he added.

Fomalhaut bis about 25 light-years from Earth. Photos taken in 2004 and 2006 show theplanet's movement over a 21-month period and suggest the planet likely orbitsits star Fomalhaut every 872 years at a distance of 119 astronomical units (AU),or 11 billion miles (nearly 18 billion km). That's about four times the distancebetween Neptune and the sun.

Kalas suspectedthe planet's existence in 2004 (published in 2005) after Hubble images hehad taken revealed a dusty belt that had a sharp inner edge around Fomalhaut.The sculpted nature of the ring suggested a planet in an elliptical orbit wasshaping the belt's inner edge. And it was.

"Thegravity of Fomalhaut b is the key reason that the vast dust belt surroundingFomalhaut is cleanly sculpted into a ring and offset from the star," Kalassaid. "We predicted this in 2005, and now we have the direct proof."

Kalas' teamalso suspects that the planet could be surrounded by a ring system with thedimensions of Jupiter's early rings, before the dust and debris coalesced intothe four Galilean moons.

What's aplanet?

The successful image results could change howplanets are defined, said Sara Seager, an astrophysicist at MIT who was notinvolved in the discoveries.

Until now,mass has been one of the critical pieces of information that could place anobject into or out of the planet club. Objects that are too massive, aboveabout 13 Jupiter masses, are considered brown dwarfs. But now formation couldalso be part of the formula. Both of the new planetary systems revealed dustydisks and suggest the planets must have formed similar to how planets in oursolar system and elsewhere are thought to have formed.

So, mostastronomers would call the four objects planets, although their masses are onlyinferred from the luminosities seen in the images.

"Takentogether, these discoveries are going to change what we call a planet,"Seager told SPACE.com. "Until now people have been arguing abouthow big can an object be and still be a planet."

Seageradded, referring to the multi-planet system, "People want to call theupper mass 12 Jupiter masses. I think it's going to force us to reconsider whata planet is, because even if they are more massive than what we want to call aplanet, they're in a disk." In addition, she said, nobody has ever spottedthree stars orbiting a host star, as would have to be the case if you were tocall the three planets something other than planets.

Aimingfor Earth-like planets

Theserecent direct images reveal giant, gaseous exoplanets in a new light for thefirst time, revealing not the effects of the planets but the planetsthemselves. The next goal would be direct images of an Earth-likeplanet, the astronomers say.

"Thediscovery of the HR 8799 system is a crucial step on the road to the ultimatedetection of another Earth," Macintosh said.

The problemis that terrestrial (Earth-like) planets are orders of magnitude fainter thanthe giant Jupiter-like worlds, and they are much closer in to their host stars.That means the glare from the star would be overwhelming with today'stechnology.

The pay-offcould be big, though, as such rocky planets could orbit within their habitablezones (where temperatures would allow the existence of liquid water).

"Thereis plenty of empty space between Fomalhaut b and the star for other planets tohappily reside in stable orbits," Kalas said. "We'll probably have towait for the James Webb Space Telescope to give us a clear view of the regioncloser to the star where a planet could host liquid water on the surface."

- Video: Alien Habitable Zone

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Video: Planet Hunter