Study: All Planets Are Born in Killer Environments

Oursolar system emerged in surprisingly good order from the violence of planetarycreation, according to a new simulation.

Researchersfound that planetary formation in the first few million years often resembles aviolent wrestling match among hungry siblings, with planets fighting to feed ongas and dust while pulling at each other with gravitational arms.

"There'smassive bodies competing with each other and flinging each other around,"said Edward Thommes, a physicist at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, and lead author on the new research published in the Aug. 7 issue of the journalScience.

Thesimulation traces the creation of a planetary system from almost beginning toend, for the first time, and suggests that our solar system started with justthe right mass to become a relatively orderly place in the universe.

"Youhave to have the conditions just right," Thommes told SPACE.com."They have to be in a fairly narrow range."

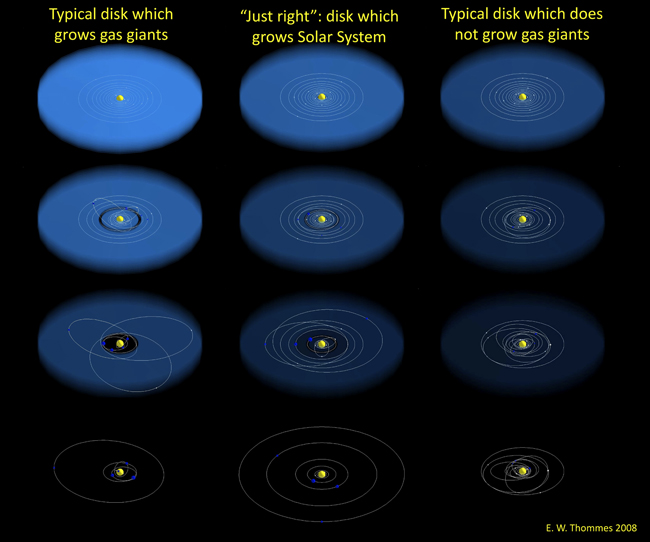

Thommesand his former colleagues at Northwestern University ran the simulation throughover 100 scenarios to see how gasgiants formed from the gas disks that surrounded young stars. Newbornplanets typically seemed to get pushed toward the central star by the gas diskremnant surrounding them.

"Thesame disk from which they're born is also trying to kill them," Thommes said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Toomuch starting mass in the disk results in a swarm of gas giants crowding intothe central star. However, too little mass produces nothing bigger than Neptune-likeice giants.

Thetussle among gas giants can typically lead to loopy elliptical orbits.Sometimes a gas giant even acts as a slingshot to throw a sibling into deepspace.

Bycomparison, our solar system's gas giants ? Saturnand Jupiter ? have nearly circular orbits that suggest less violentinteraction. The two planets also appear to have stayed close to where theygrew up, instead of migrating into the sun.

"Theynever really got into each other's face, so to speak," Thommes said."They kept their personal space."

Thesimulated planetary systems mostly line up with observations of more than 300exoplanets discovered so far. But Thommes cautioned that the observed exoplanetsrepresent those that are relatively easiest to find, or "a filteredsample" of what astronomers can see.

Theresearchers chose to sacrifice some detail in their simulation in order tomodel planetary systems from start to finish. They hope to extend their hybridmodel approach so that they can eventually model planets spiraling all the wayinto the central star. Currently, the simulation cannot track such planetsbeyond a certain point.

Anoutside essay accompanying the Science paper and written by JohnPapaloizou, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge in the UK, callsthe new simulation "compelling" and says that it achieves"reasonable success" in modeling what astronomers have observed.

Papaloizoupointed out that some simulated planetary orbits do not match up with the usualequatorial plane of star systems, something that astronomers have not seen inexoplanetary systems so far. However, he also adds that current knowledge ofexoplanetary systems remains limited.

Forhis part, Thommes remained confident that our solar system was uniquely quiet, especiallyconsidering the birthing process.

"Whatour solar system seems to represent in all of this is a peaceful and quiet formof this process," Thommes said.

- Video: Planet Hunter

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- All About Planets

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.