Dancing Asteroid Mapped in Motion

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

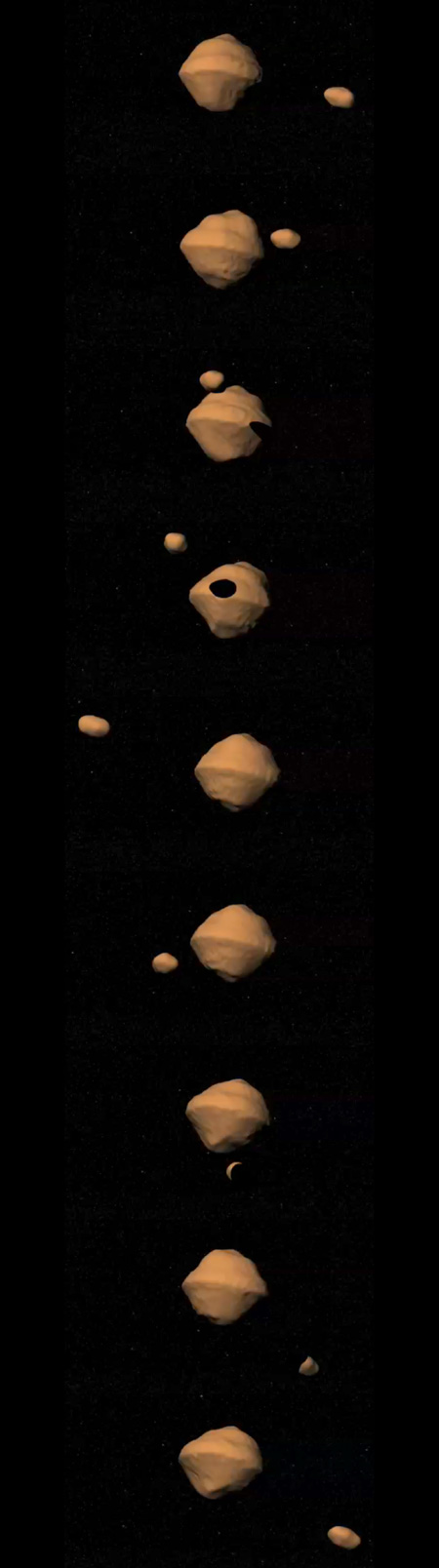

A near-Earth asteroid is made of two motley parts that dance around each other like a miniature Earth and Moon, a new study finds.

In May 2001, the asteroid 1999 KW4 passed within about 3 million miles (4.8 million km) of Earth.Scientists bounced radar off the asteroid's surface and, by measuring the strength and lag time of the returning signals, were able to calculate many of its physical properties.

The radar imaging shows that Alpha, KW4's larger component, is about one mile (1.5 km)wide and essentially a floating pile of rubble held together by gravity; about 50 percent of it is empty space.

The smaller piece, Beta, is about a quarter of Alpha's size and elongated, like a peanut. Beta orbits Alpha every 17 hours from a distance of about 1.5 miles (2.5 km).

"They are so close together that when one rotates it affects the other's movements," said study team member Daniel Scheeres of the University of Michigan.

Near break-up speed

The findings,detailed in the Oct. 13 issue of the journal Science, also reveal that Alpha is spinning [animation]close to its break-up speed. It makes one complete revolution about once every three hours; if it spun any faster, material from its equator would fly off into space, the researchers say.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As with binary stars, scientists were able to calculate properties of KW4 [image]from a distance based on how its separate parts gravitationally affect each other.

To get the same kind of detailed information from a single-body asteroid, a spacecraft would have to observe it from close orbit. NASA's Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR)Shoemaker spacecraft did just this with Asteroid 433 Eros in 2001, as did the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa with asteroid Itokawa last winter.

Some of the information gathered from KW4 could be applied to other asteroids, said Eugene Fahnestock, a study team member at the University of Michigan who helped simulate KW4's motions based on the radar data.

"A lot of the things you can tell will inform our general understanding of the internal structure of all asteroids, not just binary asteroids," Fahnestock told SPACE.com.

Propelled by sunlight

Scientists think that KW4's two pieces once belonged to a larger asteroid that broke apart during a perilously close pass by the Earth.

Another possibility is that sunlight shining on the precursor asteroid caused it to spin so fast it broke in two. Because of their odd shapes, asteroids can sometimes act like solar sails, catching sunlight the way sailboats catch wind.

KW4 is classified as a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) because it approaches relatively close to Earth compared to other asteroids. However, the latest observations show that there is no chance that KW4 will hit Earth within the next 1,000 years, Scheeres said.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.