To Make a Moon Village, Think Beyond Science and Engineering (Op-Ed)

Tomoya Mori is a senior at Brown University pursuing interdisciplinary studies in space exploration, multimedia and education. He is a co-founder at Metaplaneta, a creative think tank that investigates a multidisciplinary approach to space. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

"Been there, done that." President Barack Obama famously used that line to help shift the world's attention from the moon to Mars as a space destination in recent years, though the debate on where to go next continues. But whether humanity wants to colonize the moon or terraform Mars, establishing a settlement on other celestial bodies is a challenge of immense scale.

So a more important question to ask is this: What does it take to establish a permanent human presence outside of Earth?

Beyond the usual suspects

This question presents a great diversity of challenges that transcend disciplines. It goes beyond the realm of science and engineering, the two fields often considered the core of space exploration, and include politics, law, architecture, business and design. Extending a human presence beyond the planet will depend on diversifying the space community to include broader interests and perspectives.

Already, a number of institutions collectively foster a multidisciplinary environment within the space industry. The Sasakawa International Center for Space Architecture (SICSA) in the University of Houston offers the world's only master of science program in space architecture. Other institutions educate students about space law and policy, including the George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs in Washington, D.C., and Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston.

These unique programs equip their students with specialized knowledge and skills for the field of space travel. The real value, however, is in bringing new perspectives to the ever-growing space industry. [Moon Base Visions: How to Build a Lunar Colony (Photos )]

Currently, most of those disciplines are functionally independent. Rarely do politicians talk about the architecture of space vehicles, or scientists talk about the potential of space business. But in reality, those fields are so intertwined that interdisciplinary fusion can be a real game-changer.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The space industry should focus not merely on diversification, but also on the process by which diverse disciplines interact. It is time to take a more transparent, integrative and interdisciplinary approach to space exploration.

One method for integrating disciplines, called the integrated design approach (IDA), has proven effective in sustainable design and could provide the same benefits for space.

Lessons from an HVAC

Traditionally, designers have used a linear process to construct sustainable buildings. Architects make sketches and pass them on to the engineers, who evaluate the designs and then assign subcontractors, and so on. However, with that approach, time and money are already running out by the time conflicts and problems arise.

IDA is successful because it involves all project members from the beginning, allowing them to identify and resolve potential conflicts earlier in the process. And the multidisciplinary environment forces project members to think outside their immediate areas of expertise, inspiring innovative solutions to problems and generally producing more energy-efficient and cost-effective results.

For example, in the book "Integrative Design Guide to Green Building" (John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2009), the authors present real-life situations in which IDA led to a surprisingly efficient outcome. The book was written by 7group, a multidisciplinary team dedicated to sustainability and regeneration, and Bill Reed, a proponent and practitioner of sustainability and regeneration.

In the example, a team of architects, landscape designers and engineers was determining the placement of an HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) system in an office building, and the architect asked the mechanical engineer to provide an answer. The engineer was stunned, at first. Even though he had more than 20 years of experience designing HVAC systems, never in his life had anyone asked him where to locate one. After a few minutes, he provided a solution that turned out to be extremely efficient and cost-effective. Instead of placing the necessary mechanical room on the roof, which the architects had done in the last project, the engineer proposed placing heat-pump units on the ground floor of the building. Not only did this solution reduce the piping work and save $40,000 in construction costs, it also led to simplified maintenance and significant operational savings.

From that experience, the team realized the importance of questioning assumptions. All components of a building are interdependent, and therefore everyone's input should be respected — not only individuals within one's own area of expertise, but also everyone else in a team.

Innovative solutions or strategies often come from unexpected sources, and in this example, the multidisciplinary environment was critical to promoting openness and stimulating everyone's creativity.

Finding transparency (literally)

The work of Danish architects in the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) provides another illustration. In 2009, the Urban Planning Department of Tallinn, Estonia, and the Union of Estonian Architects held an international competition for a new town hall in in Tallinn. Throughout the design process, the BIG architects received input from the jury about the citizens’ needs and take into account of the city’s governance system. The design had to be flexible and accommodate unexpected demands.

The BIG group's solution was simple yet quite novel; it was to increase the transparency between the citizens and politicians, to improve governance and the town's participatory democracy.

The BIG town hall design has myriad glass windows and an open structure, offering the politicians daylight and a view of the city marketplace, and offering the town's citizens a chance to see their elected officials at work.

Although the mayor of Tallinn had expressed his hope to build a new city hall, the proposal still remains a mere design, albeit one that shows the effectiveness of integrated design. Here, the architects not only provided a great working space for politicians, but also unified the city as a whole.

Space habitation is not just space travel

Space infrastructures are, in essence, organic systems. They need to be more self-sustaining than any regenerative and sustainable green buildings on Earth. And because of the constrained living conditions they present, such buildings must include input from the astronauts and travelers who might use them, and the input from a range of designers, engineers and others.

For example, the habitation modules of the International Space Station must address energy and thermal balance, waste management, mechanical structure, and architecture, in addition to comfort and privacy, among other factors.

The Habitation Design Center in NASA's Johnson Space Center often invites astronauts as consultants to improve module designs and make them more human-centered. It may seem obvious, but it is crucial that space vehicles be designed with feedback from astronauts, instead of becoming function-based machines like fighter planes. Rarely does one see inhabitants involved in the design process of an Earth-bound structure.

For missions, like space colonization, of a larger scale, the IDA approach is even more necessary. Settling on a celestial body is far different from simply going there. To establish a sustainable living space in such a hostile environment, one needs to not only think about science and engineering, but also consider psychological, architectural, societal, political and economic aspects.

Targeting the moon

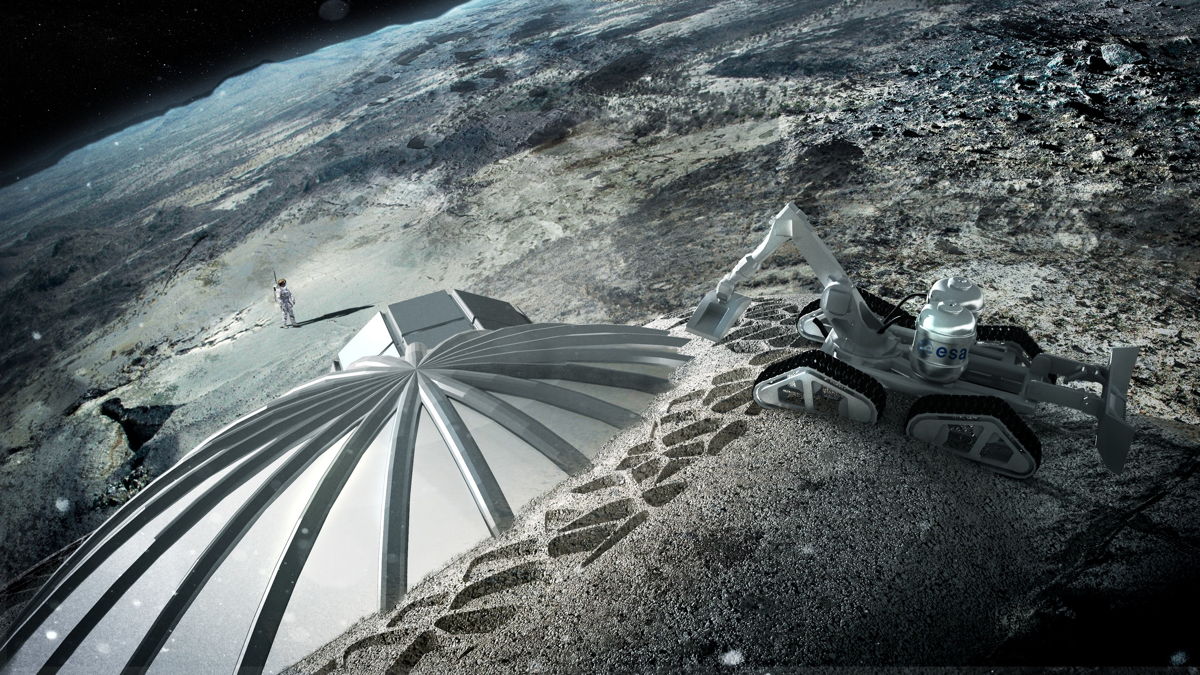

Today, many of the world's space agencies have expressed interest in sending humans to the moon. Johann-Dietrich Woerner, the director general of the European Space Agency (ESA), has been pushing his vision to establish a moon village. Although the agency has yet to officially approve that plan, his message has gone global.

Despite the hint of novelty it carries, the concept of lunar colonization existed long before the Apollo era. Numerous books and papers have presented promising plans for a lunar colony, but none have been realized, or even attempted. One of the fundamental obstacles is financial. Even if the moon village concept succeeded, most taxpayers would not understand why it was worth the cost.

And yet, the moon has the potential to help humanity grow as a species. A lunar colony could be a model for a sustainable ecosystem, a testing ground to strengthen international collaboration, a giant laboratory for cutting-edge scientific experiments and technological innovation, a platform for new businesses, a stepping-stone for further exploration of the solar system, and a mental exercise for challenging norms.

But if humanity is to establish a lunar colony, the world must employ IDA, involving all key players at the start.

Space horizons 2016: international city on the moon

Over the weekend of Feb. 19 to 21, Brown University in Rhode Island will host Space Horizons 2016, a student-focused, three-day integrative workshop that brings students and professionals from all disciplines to conceptualize an international lunar city.

The event will consist of four workshops — Politics, Infrastructure, Science, and Business & Technology — that will ask several questions: What would politically motivate participating countries? What is the economic value of a lunar city, and what commercial opportunities can sustain the lunar economy? What new experiments would emerge on a lunar base, and how would they help humanity live on the moon and beyond? What infrastructure is required to sustain a lunar ecosystem?

Through the integrated-design approach, participants will be encouraged to think beyond their immediate expertise, and to recognize the connections between their skills and the space industry, making space more tangible to everybody. Each workshop will have experienced mentors and professionals, including representatives from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the Lunar and Planetary Institute, PoliSpace, Sasakawa International Center for Space Architecture, Masten Space Systems, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Brown University, Yale University in New Haven, the University of Central Florida and the Rhode Island School of Design. Ultimately, the findings may lead to a joint project or publication.

But Space Horizons 2016 is not the first to take on the moon village concept. At the end of last year, ESA European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) hosted "The Moon Village Workshop", which took place in conjunction with International Symposium on Moon 2020-2030. The workshop invited professionals and students from all over the world to discuss and propose ideas to consolidate visions for the moon village concept. The participants were split into three groups: Moon Habitat Design, Science and Technology Potential in the Moon Village, and Engaging Stakeholders.

The three working groups came up with several recommended actions to be taken by the director general of ESA, including the design and operations of a moon-base simulation at the European Astronaut Centre and the engagement of the most direct stakeholders, such as media, national governments and citizens, at the next ESA Ministerial Council Meeting.

It takes time for educational strategies to prove their effectiveness. And as long as the moon village concept remains a vision, it will be challenging to involve people from nonspace industries, especially in an era in which the space industry is generally considered exclusive to rocket scientists.

However, the future of space exploration is in widening the community. Most innovative ideas are the products of interdisciplinary fusions. Just as much as technological advancements will accelerate space exploration, broader interests and perspectives will also catalyze the process of establishing space colonies. The integrated-design approach has the potential to not only open up new perspectives, but also offer a younger generation an opportunity to design the future of space exploration and radically change humanity's perception of space. It is those people who will advance society into the universe.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.