Black Hole's Epic Belch May Solve Stellar Mystery

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

KISSIMMEE, Fla. — A black hole's epic "burp" may help solve one of the deep mysteries of the galactic core.

The dust-filled expanses of spiral galaxies like the Milky Way are bursting with star formation — the dustier the area is, the more likely it is for new stars to form there. But astronomers have found that stars rarely form in the center of a galaxy, where a supermassive black hole often rests, and researchers don't know why. Smaller, elliptical galaxies also show little star formation.

A black hole relatively close to the Milky Way — a mere 26 million light-years from earth — has shown evidence of a huge X-ray blast outward that may have "snowplowed," or swept away, nearby star-forming dust. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

"This is the best example of snowplowed material I've ever seen," Eric Schlegel, lead author on the new study and researcher at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said in a press conference today (Jan. 5) at the American Astronomical Society's winter meeting today in Kissimmee, Florida. "This is clearly a way of ejecting gas from a galaxy."

"For an analogy, astronomers often refer to black holes as 'eating' stars and gas," Schlegel added in a statement. "Apparently, black holes can also burp after their meal."

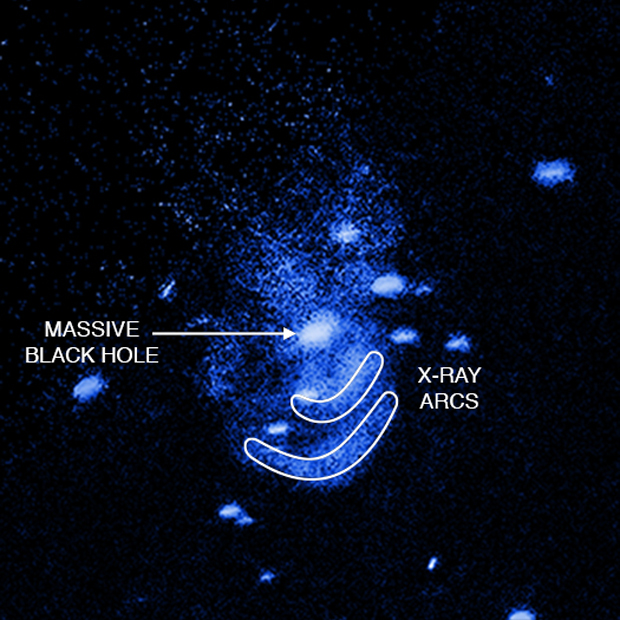

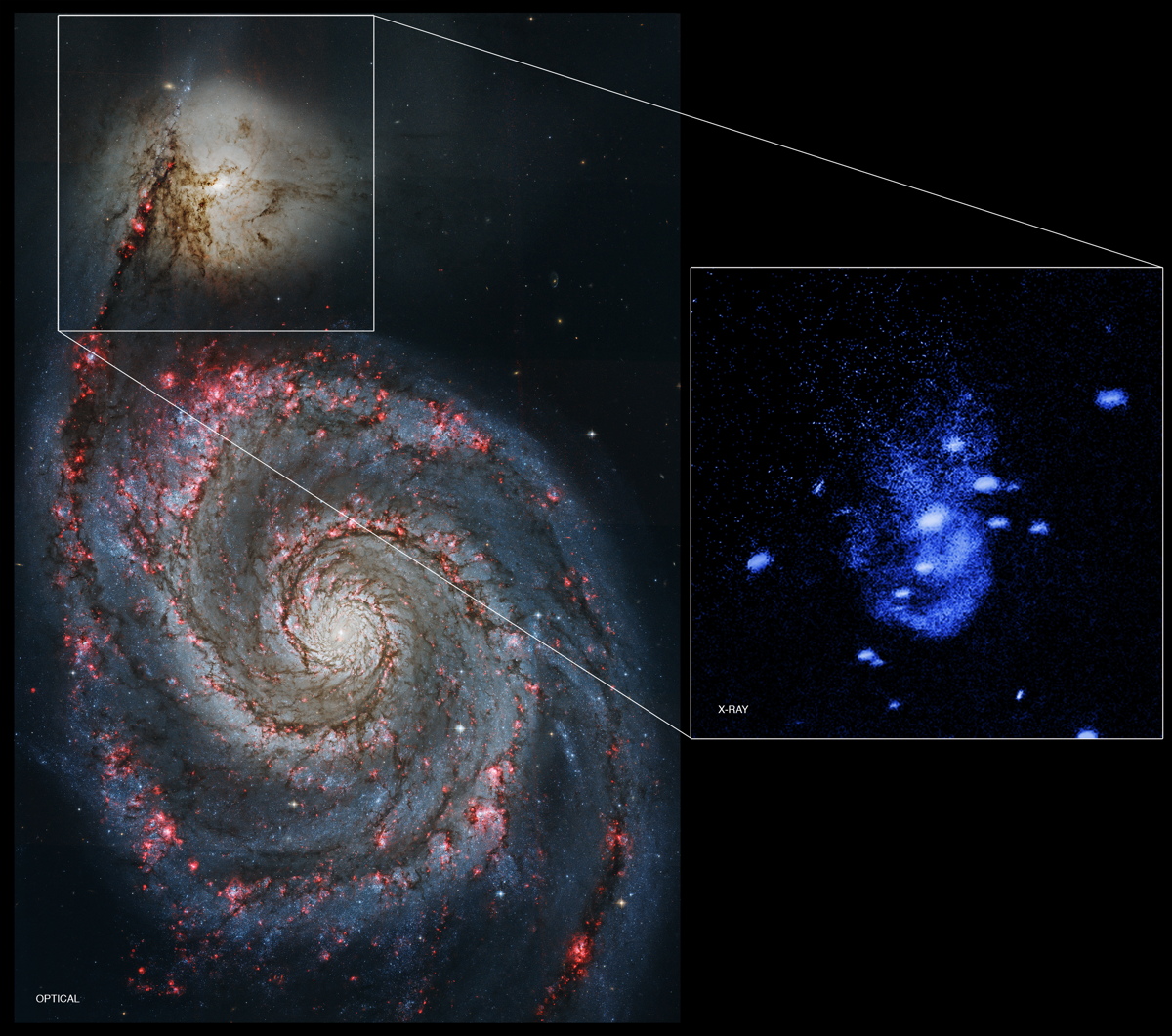

Schlegel's team analyzed data from the orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory to investigate the dwarf galaxy NGC 5195, which is in the process of merging with the flashier Whirlpool galaxy. The researchers observed two arcs of X-rays near the center of the dwarf galaxy, which appear to be the remnants of two huge blasts outward from the black hole. Plus, the view from an optical telescope revealed a region of cooler hydrogen gas just past the X-ray arcs, which suggests the blasts pushed dust outward.

Schlegel said that dust and gas from the galaxy's collision with the Whirlpool galaxy could have slingshotted around the black hole, but that he finds that unlikely. More probably, the black hole actually reacted to the large additional quantities of dust pushed into its path, resulting in the "burp," he said. The inner X-ray arc may have taken about 1 million to 3 million years to expand to its current position, and the outer one 3 million to 6 million years, officials said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There's much more to explore about this system, Schlegel noted. "How that reaction goes is very unclear, but I think it's clearly something that's worthy of study at other wavelengths," he said at the conference, "in addition to using simulations to try to [replicate] it."

The researchers said they suspect this type of reaction might have been much more common in the early universe, when galaxies were more densely packed together, but this "nearby" galaxy exhibiting the behavior is an exciting opportunity to see it happening up close, with less distortion. The effect can reach further out than the dramatic winds that push material away from a black hole, and it is an interesting new example of how a supermassive black hole's activity can shape a galaxy, a process called feedback, the researchers said.

The scientists also found something strange along the border of the blast: Although the "burp" may have swept dust-forming gas away from the center of the galaxy, enough was pushed up together outside the outer arc to form new stars, as well.

"We think that feedback keeps galaxies from becoming too large," co-author Marie Machacek, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in Massachusetts, said in the statement. "But at the same time, it can be responsible for how some stars form. This shows that black holes can create, not just destroy."

These results have been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.