Going Interstellar: Q&A With Author Kim Stanley Robinson

Interstellar travel could be humanity's greatest challenge — or humanity's greatest mistake.

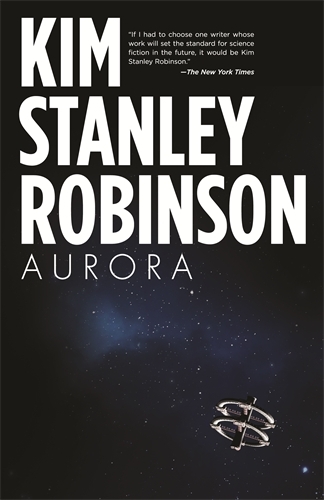

The narrative of Kim Stanley Robinson's new novel, "Aurora" (Orbit Books, 2015), which comes out today (July 7), begins 159 years into a 170-year mission to the star Tau Ceti and a suspected Earth-like moon orbiting one of its planets. The book traces the complexities of life aboard a multigenerational starship and the decisions the pioneers face as they seek to colonize the distant exomoon.

Robinson offers a fantastic entry into the starship sci-fi tradition with precise scientific detail and an incredible number of moving parts — more than 2,000 people live on the ship, plus all the lifeforms required to sustain them nestled in 24 different biomes. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

We loved it so much, we made "Aurora" Space.com's Book of the Month for July.

In a recent interview, Space.com talked with Robinson about the feasibility of interstellar travel, artificial intelligences, storytelling and lessons for humanity's future.

Space.com: Your stories range from the distant past to the far future, which both bring their own challenges confronting humanity. What's interesting about the particular challenge that you cover in "Aurora" — interstellar travel?

Kim Stanley Robinson: More than once [in past books], there's been a group that headed off to the stars, and they disappear out of the story. It's often seen as kind of a desperate act. In [previous novel] "2312" [Orbit Books, 2012], I began to make the case that although the solar system is in our neighborhood, so to speak, and we can definitely visit it and set up scientific stations all over the solar system, that going to the stars — the new data about what we are as bodies (our bodies are biomes) — made me begin to question the starship project, begin to worry that the stars are simply too far away, even the closest ones.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Aurora" is a story that I wanted to tell to kind of test out that thought. I don't think people will try it until they are really feeling quite competent in the solar system, and then it will become kind of a religious act. I think there's a certain craziness in it, or pointlessness — the point seems to be religious, and having to do with species immortality or something like that.

It's a little questionable, why we want to do it. And yet it's a meme in the culture. So I thought it would make a good story to test out that thought and write down everything that I thought would happen as a sort of realism. Try to take all the parameters and all the difficulties involved as seriously as I could and see what kind of story I got.

Space.com: Why did you choose Tau Ceti as the destination star system?

Robinson: Of course, Alpha Centauri is close, but we know that its star is a little bit weird for us, and then Barnard's Star -- very intriguing -- often gets mentioned, and then Tau Ceti just because it's a solar analogue and it's nearby. And now, of course, we've got five planets there that we know of. Planet E and F are at the inside and the outside of the habitable zone where water would be liquid on the surface. But one of them is five Earths in mass, and the other one is six Earths in mass, I think. Unless one of them does prove to have a moon, a big Earth-like moon, those planets are useless to humans.

Space is just too big, and even the so-called nearby stars — we're finding out more about them, and they're not going to be suitable, so we're going to have to go even farther. To get an Earth analogue in the habitable zone, it could be way farther than the nearest stars, which complicates the problem even more.

But Tau Ceti is clearly a figure in science fiction now, so it's great to join that tradition and the starship tradition in science fiction. I'll be interested to see how this book fits into the whole starship tradition. [How Interstellar Travel Works (Infographic)]

Space.com: What aspect of the book's science was the most fascinating to develop?

Robinson: There's a bit of orbital mechanics that — I went to NASA Ames [Research Center in Moffett Field, California], and I have a friend there, Chris McKay, who has been my help ever since the Mars books on technical questions about Mars.

So many times I've gathered together a bunch of questions, and he organizes a lunch at NASA Ames and just asks people that he knows if they're interested in coming to the lunch. And then I pop up my laptop and ask questions and type really fast. When I gave them my first parameters they said, "well, that just won't work — that's like trying to stop a bullet with tissue paper." And so I said, "well, let's make it work," and so we began to change the parameters.

Of all the scientific questions, the starship questions were a lot of fun, too — the ecology of the starship and the design. I had to draw the starship so I could stay located, make very rough schematics of which biome led to which biome and the two rings, the A ring and the B ring. That, too, was a ton of fun. [Gallery: Visions of Interstellar Starship Travel]

Space.com: "Aurora" has rather unconventional narration. Can you tell me about how you chose to use that narrator?

Robinson: For me, it was the key that unlocked the book. It came to me in a dream, and I woke up from the dream, thinking, "It's the starship that should be the narrator."

I had been thinking about quantum computers and artificial intelligence for "2312" — I had been thinking about it for quite some time. I never believed in artificial intelligence, I still kind of don't compared to most thinkers and science fiction writers, but I sure thought that it was a good idea, that for sure it would have to be a really powerful AI to run the starship. And if you have a quantum computer, there's the possibility for some different kinds of computation than classical computers.

Once I committed to the AI on the ship as the narrator, it changed everything, because then the AI has to figure out how to write a novel. That made me laugh. There was a lot of comedy involved because it isn't obvious what's important to tell in a novel, and that's for damn sure. I've spent almost 40 years puzzling over what's important to tell out of daily life and what makes the plot, and how you tell the story of a group by representative individuals.

These questions are impossible; there's no algorithm that will answer these questions for you, and so when [the ship's engineer] Devi tells the AI to keep a narrative account, that's a terrible request.

After writing "Aurora," what are your overall thoughts on space and interstellar travel?

The solar system is our neighborhood, and going into space itself, exploring the solar system, is actually part of planetary maintenance, you might say. I have a huge enthusiasm for the space program when it comes down to the solar system and exploring it for the health of Terran [Earth] civilization. It's all part of a larger argument to try and figure out what we should be doing right now, what's important.

What about interstellar colonization, in particular?

There are a lot of people, even powerful, influential people, who seem to think that the goal of humanity is to spread itself. I want this book to make people think really hard about — maybe there's only one planet where humanity can do well, and we're already on it.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.