NASA Europa Mission May Search for Signs of Alien Life

MOFFETT FIELD, Calif. — A potential NASA mission to Jupiter's moon Europa may end up hunting for signs of life on the icy, ocean-harboring world.

NASA officials have asked scientists to consider ways that a Europa mission could search for evidence of alien life in the plumes of water vapor that apparently blast into space from Europa's south polar region.

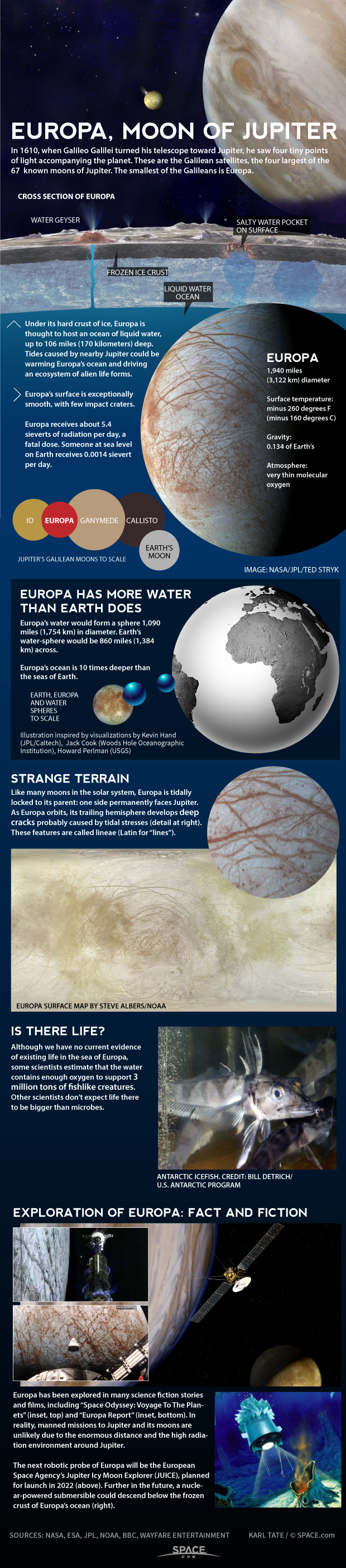

These plumes, which NASA's Hubble Space Telescope spotted in December 2012, provide a possible way to sample Europa's ocean of liquid water, which is buried beneath the moon's icy shell, researchers say. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

"This is our chance" to investigate whether or not life exists on Europa, NASA science chief John Grunsfeld said here Wednesday (Feb. 18) during a Europa plume workshop at the agency's Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. "I just hope we don't miss this opportunity for lack of ideas."

Europa flyby mission

NASA has been working on Europa mission concepts for years. Indeed, last July, agency officials asked scientists around the world to propose instruments that could fly aboard a Europa-studying spacecraft.

The quest to explore the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) moon got on firmer ground earlier this month when the White House allocated $30 million in its fiscal year 2016 budget request to formulate a Europa mission. (NASA was allocated a total of $18.5 billion in the request, which must still be approved by Congress.)

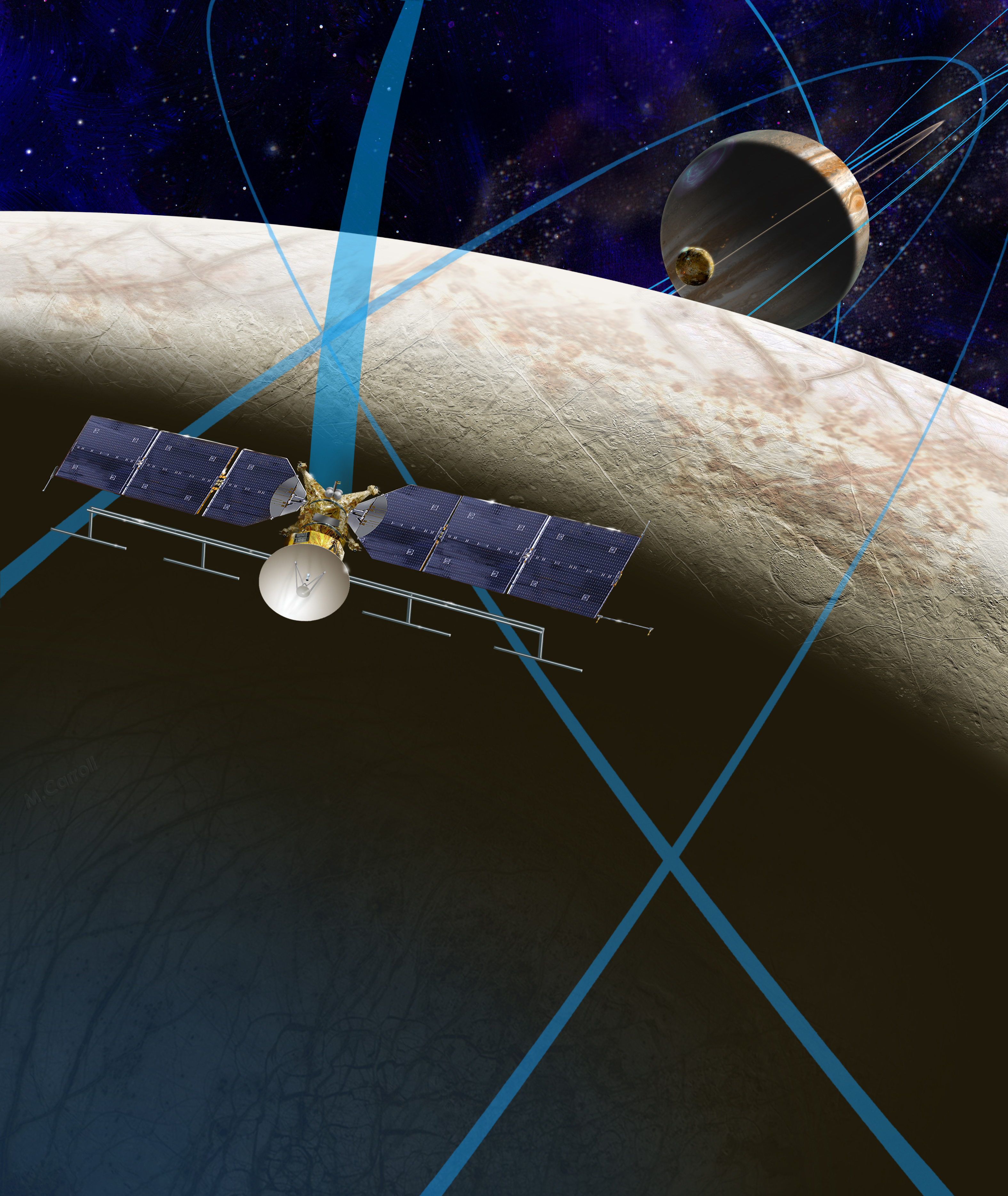

NASA is zeroing in on a flyby mission design, something along the lines of a long-studied concept called the Europa Clipper. As currently envisioned, Clipper would travel to Jupiter orbit, then make 45 flybys of Europa over 3.5 years, at altitudes ranging from 16 miles to 1,700 miles (25 km to 2,700 km).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $2.1 billion mission would study Europa's subsurface ocean, giving researchers a better understanding of the water's depth, salinity and other characteristics. The probe would also measure and map the moon's ice shell, returning data that would be useful for a future mission to the Europan surface. [Europa and Its Ocean (Video)]

And now, it appears, NASA would like to add plume sampling to the Europa mission's task list, if possible. Grunsfeld urged workshop attendees to "think outside the box" and come up with feasible ways to study the moon's plumes.

If one such idea could be incorporated into the upcoming mission, so much the better. After all, the earliest that Clipper (or whatever variant ultimately emerges) could blast off for Europa is 2022 — and, using currently operational rockets, the craft wouldn't arrive in the Jupiter system until 2030, Grunsfeld pointed out. (Use of NASA's Space Launch System megarocket, which is still in development, would cut the travel time significantly.)

And there's no telling when NASA will be able to go back to Europa. (Europe is developing its own mission called the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer, which is scheduled to launch in 2022 to study Europa and two other Jovian satellites, Ganymede and Callisto.)

Grunsfeld stressed that he and other NASA higher-ups aren't pushing to turn Clipper into a plume-centric project; the core goals of the Europa mission will remain centered on assessing the moon's ability to support life, whatever comes out of the Ames workshop. But he doesn't want the plume opportunity to slip away for want of effort or focus.

"I don't want to be sitting in my rocking chair 20 years from now and think, 'We should have done something,'" Grunsfeld, a former NASA astronaut who helped repair and service Hubble on three separate space shuttle missions, told Space.com at the workshop.

Flying through the plumes?

A probe such as Clipper could zoom through the plume, which may rise as high as 125 miles (200 km) above Europa's surface; the probe could snag material using an aerogel collector, some workshop presenters said. The basic idea was demonstrated by NASA's Stardust mission, which returned particles of the Comet Wild 2 to Earth in January 2006.

Researchers would of course love to analyze bits of Europa material in well-equipped labs here on Earth, but bringing samples back is likely beyond the scope of the flyby mission currently under consideration. And it may be possible to detect biomolecules onsite, using gear aboard a Clipper-like probe, researchers say.

For example, spotting a set of amino acids that all display the same chirality, or handedness, in plume material would be strong evidence of Europan life, astrobiologist Chris McKay, of NASA Ames, said at the workshop. (Here on Earth, all life uses "left-handed" versions of amino acids, rather than "right-handed" ones.)

"If you get 20 amino acids, all with the same chirality, that would be, I think, compelling," McKay said, adding that spacecraft such as NASA's Mars rover Curiosity and Europe's Rosetta comet probe have the ability to determine chirality in sample molecules.

But collecting enough plume material to perform such analyses will likely prove extremely challenging. Indeed, it may require flying so low and so slowly that it makes more sense to send a lander down to the Europa surface through the plume, said astrobiologist Kevin Hand of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

And all of this discussion assumes that the spacecraft will be able to find the water vapor when it gets to Europa. At the moment, the plume remains unconfirmed; scientists have pointed Hubble at Europa repeatedly since the initial December 2012 detection, but have come up empty in attempts to spot it again.

So, if the plume exists, it is apparently sporadic or episodic, not continuous like the powerhouse geysers that erupt from the south pole of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. (If Europa's plumes are continuous, they must usually be fairly weak, ratcheting up to levels detectable by Hubble only occasionally.)

The plume discovery team plans a number of additional Hubble observations through May of this year. NASA officials, and much of the planetary science community, are eagerly awaiting the results.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.