Big Meteor Explosion on Moon Shows Lunar Exploration Risks

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

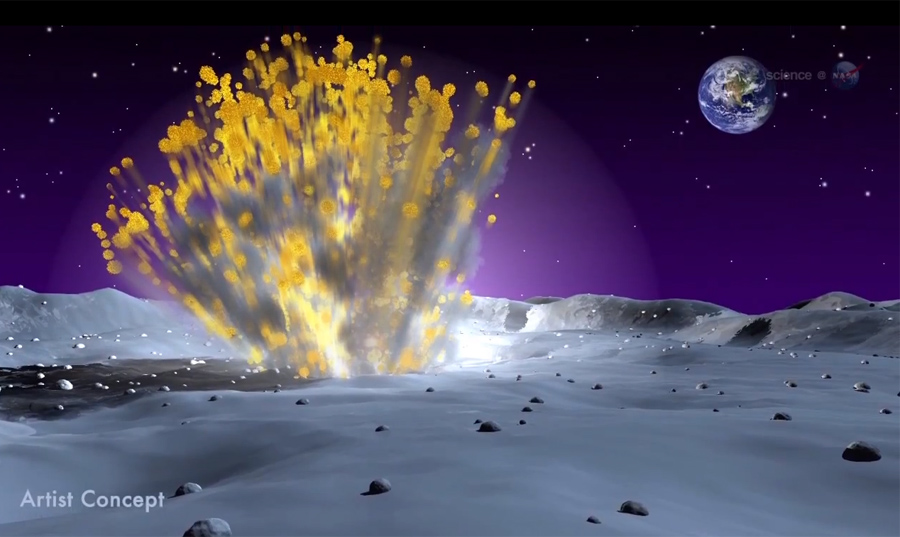

The dramatic meteorite strike that blasted out a big crater on the moon two months ago shows just how perilous manned lunar exploration can be.

A 1-foot-wide (0.3 meters) rock slammed into the lunar surface at 56,000 mph (90,120 km/h) on March 17, creating a fresh crater 65 feet (20 m) wide. The crash caused the biggest and brightest explosion scientists have seen since they started monitoring lunar meteorite strikes in 2005.

"The flash was so bright it saturated the camera," said Bill Cooke, head of the Meteoroid Environment Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. The lunar blast was the equivalent of 5 tons of TNT going off, scientists said. [See video of the bright moon crash]

Space rocks of similar size hit Earth every day or two, but our atmosphere generally burns them up completely or breaks them into small pieces that do little damage when they hit the ground. The moon lacks such a protective shield, however, and thus takes such collisions squarely on the chin.

Future manned moon missions will have to take the exposed nature of the lunar surface into account. Lunar bases could be buried underground, for example, to hide from meteorite strikes and the relatively high radiation levels at ground level (another consequence of the moon's having no appreciable atmosphere).

"Nothing like a few meters of ground to help shield you," Cooke told SPACE.com via email.

But astronauts who venture onto the surface to do exploration or science work would put themselves at risk. And relatively large space rocks like the one that hit on March 17 would not be their primary concern.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The big risk to humans there is that posed by smaller particles (millimeter-size) capable of penetrating a spacesuit," Cooke said. "This dwarfs the risk to an outpost on the surface."

The meteorite problem on Mars would not be so serious, as the Red Planet's carbon-dioxide-dominated atmosphere gives it some level of protection.

Still, Mars' atmosphere is just 1 percent as thick as that of Earth, so many rocks manage to reach the surface. In fact, a new study estimates that about 200 meteorites slam into the Red Planet every year, most of them no bigger than 3 to 6 feet (1 to 2 m) across.

NASA is planning on sending astronauts to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s, and several private organizations also have their eyes on the Red Planet.

The nonprofit Inspiration Mars Foundation, for example, aims to launch two people on a flyby mission around the Red Planet in January 2018. And the Netherlands-based nonprofit Mars One hopes to land four astronauts on the planet in 2023 as the vanguard of a permanent settlement.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.