'The solar system on demand': HEO Robotics aims to push spacecraft imaging deep into the final frontier

"The national security establishment has already been doing this for five decades but thought that no one could replicate it, so they made it highly classified."

An Australian firm leading the way in providing images of spacecraft in low Earth orbit is making moves to expand its capabilities to higher orbits — and possibly, in the long run, to solar system destinations.

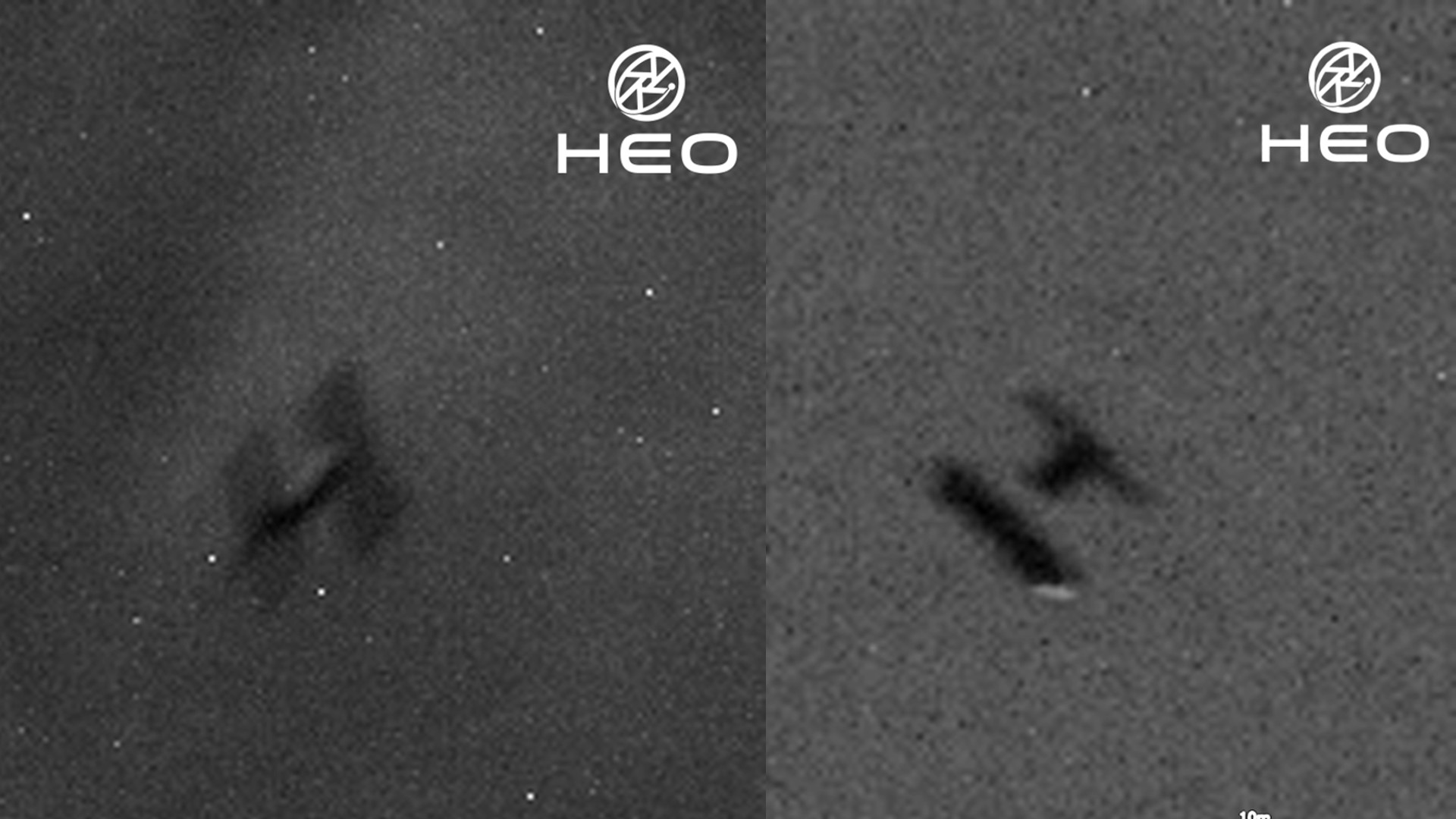

HEO, also known as HEO Robotics, has made a splash with sensational images of spacecraft in low Earth orbit (LEO) that were taken by other spacecraft, or "non-Earth imaging" (NEI). Prominent examples include closeups of the International Space Station (ISS) and China's Tiangong space station, as well as photos of the European Space Agency's ERS-2 satellite as it tumbled into Earth's atmosphere in February 2024. Such images are taken during calculated close approaches to spacecraft of interest by partner satellites.

While these photos are striking, clients can also obtain images they need for anomaly detection, operational awareness and risk mitigation, as well as more general space domain awareness, or the ability to track, identify and understand the behavior of satellites and space debris.

Will Crowe, co-founder and chief executive of HEO, spoke with Space.com at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Sydney in early October, describing the company's plans to deliver images of spacecraft and more even farther away from Earth.

HEO, founded in 2019, began as an asteroid-mining venture but quickly pivoted to find a business case. It started pushing boundaries as soon as it began imaging spacecraft, though what was possible or not was not immediately clear.

"The national security establishment has already been doing this for five decades but thought that no one could replicate it, so they made it highly classified," Crowe said.

"No one without a classification knew it was possible because it was just very secretive," he added, laughing. "But we didn't know we shouldn't know that, so we just started playing, and there was no one to stop us, because we're here in Australia."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The company is now looking to advance to providing images of spacecraft in geostationary orbit (GEO), a special orbit at which satellites orbit at a speed that keeps them effectively fixed over a spot on the equator 22,236 miles (35,786 kilometers) below. GEO is inhabited by, among other craft, high-value communications and weather satellites.

HEO does not operate its own satellites. In terms of acquiring images, HEO partners with a range of Earth-imaging companies such as Blacksky and Satellogic and makes use of the satellites when they are not active — for example, when they're passing over the oceans. But GEO, unlike LEO, has a scarcity of satellites with cameras. This means HEO will be looking to get its own imagers and sensors and required software on satellites getting ready for the trip to GEO.

"Getting to GEO is going to be very challenging, so we're focused on that right now," Crowe said. "Huge revenue unlock for us, huge capability unlock for our customers. So that's our main technical goal over the next 12 months."

The company also signed a three-year memorandum of understanding with satellite servicing and orbital sustainability firm Astroscale at IAC in Sydney, deepening cooperation on monitoring, assessing and ultimately servicing allied defense, government and commercial assets.

Notably, Astroscale has performed a fly-around of a spent rocket stage in orbit, as part of its plans to start deorbiting pieces of space junk. HEO can help with such operations, Crowe explained. "It's just good practice to have outside eyes looking in. Issues can happen to a sensor on board, but also you can get a different perspective." The agreement between HEO and Astroscale also covers extending cooperation into GEO and geostationary transfer orbits.

HEO also recently received the first National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Tier-3 license for a commercial optical camera operating in high LEO (above 800 kilometers, or 500 miles), a sign of growing official recognition of non-Earth imaging as part of space safety infrastructure.

This expansion to a higher Earth orbit is, however, just another step in a broader plan. The long term vision? "The solar system on demand," said Crowe. "If you want to go see an asteroid, we will enable that mission."

"We're starting with just the asteroids that are coming through the Earth-moon system," he added. "But there's no reason why we can't enable it for everything: the asteroid belt or all the other various asteroid classes. It should be possible. You just need enough cameras and enough interesting orbits such that they can always achieve the mission."

HEO is already normalizing non-Earth imagery, and the leap from Earth orbit to more distant destinations may well follow, repurposing and reimagining what is possible in space.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.