These Ancient Galaxies Are Far Brighter Than Expected. Does That Signal a Cosmic Turning Point?

By staring at the sky for over 200 hours, the Spitzer Space Telescope collected light that finally reached Earth after a 13-billion-year voyage through space.

This light left its origin so long ago that researchers studying this imagery are essentially peering back — way back — in time, to the ancient cosmic past.

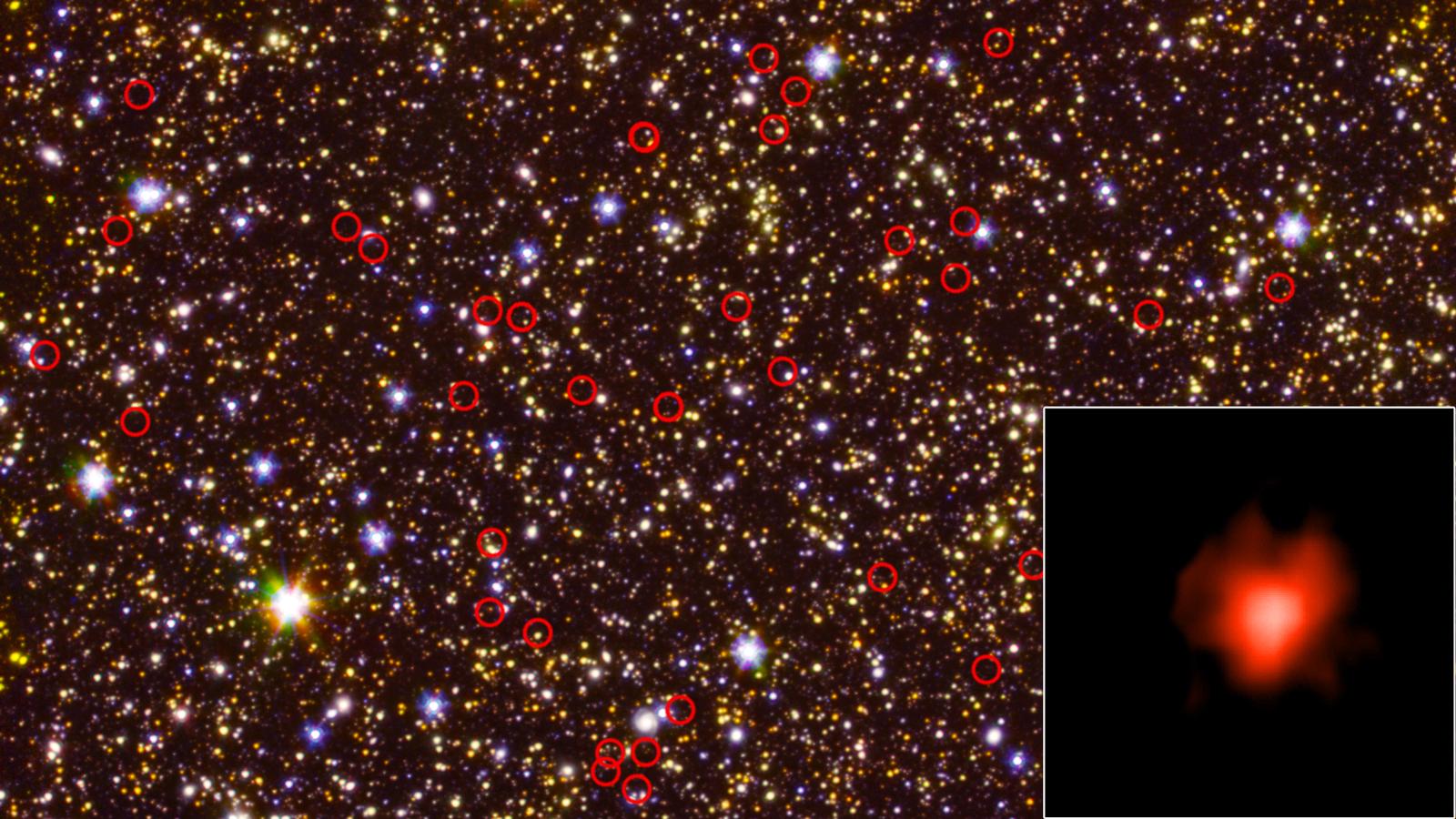

Using Spitzer data, a research team observed 135 distant galaxies and found that these celestial bodies, which formed over 13 billion years ago and just 1 billion years after the Big Bang, were brighter than expected. Researchers coupled their Spitzer findings with archival data from the Hubble Space Telescope in a recent paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Related: This 13.5-Billion-Year-Old Star Is a Tiny Relic from Just After the Big Bang

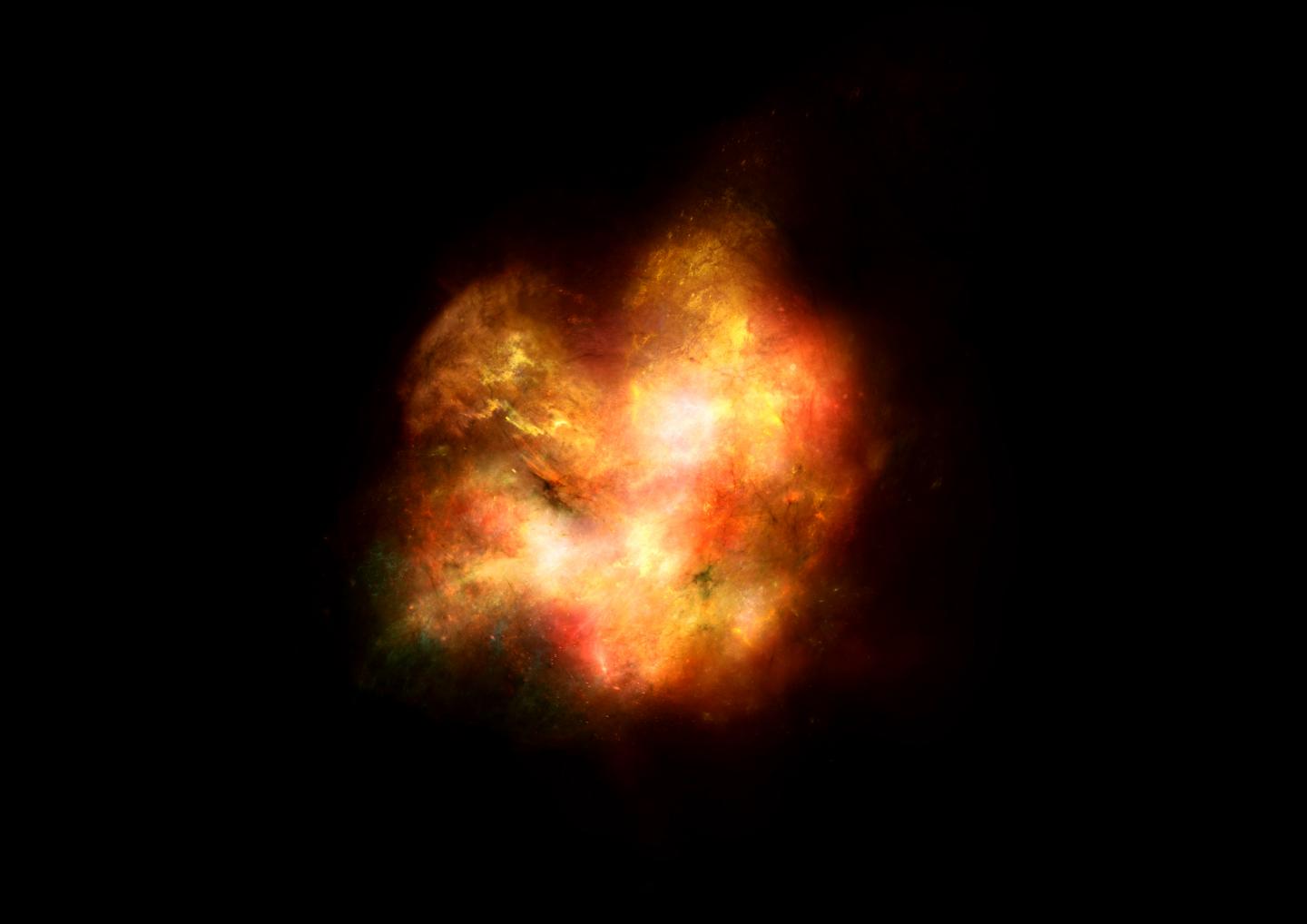

These 135 galaxies were particularly bright in two wavelengths of infrared light, which was created by radiation mingling with galactic gases like hydrogen and oxygen, according to a statement released May 9 — showing that the galaxies were releasing a high level of so-called ionizing radiation. When this type of radiation in the early universe hit abundant neutral hydrogen, it ionized it — imparting charge and kickstarting what's called the Epoch of Reionization, which coincided with the first stars' formation.

One of the biggest questions in a branch of astronomy that studies the origins of the universe, observational cosmology, is the mystery behind what produced so much of this ionizing radiation that it affected all the hydrogen in the early universe.

These galaxies might help point researchers in the right direction, because their light began its journey soon after this period, at around the time that the universe finally took the shape it appears today, soon after this period.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

''These new findings could be a big clue,'' Stephane De Barros, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, said in the statement .

These new results provide details about how the universe was evolving at this billion-year mark, but more research is needed to understand even farther back to the first stars, which were generated earlier than Spitzer can peer back.

The team suggested in the statement that the James Webb Space Telescope project, which includes a science mandate to study this era of cosmic time, could provide the missing links to these and other questions about the origins of the universe.

The new work was detailed April 4 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

- Andromeda Galaxy Twinkles in a Colorful Sea of Stars (Photo)

- Hubble Telescope Reveals What 200 Billion Stars Look Like (Photos)

- Ghostly Remains of a Dead Star Revealed in Infrared Light (Photo)

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.