Why Physicists Are Planning to Drive Antimatter Around in a Moving Van

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Antimatter is about to go on its first road trip.

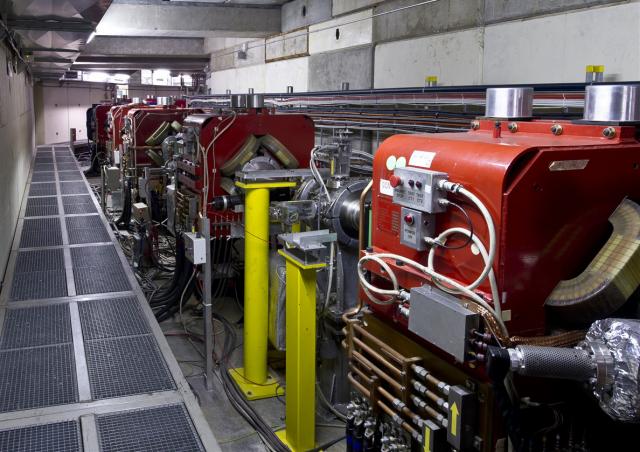

Until now, the list of things that travel in vans has pretty much included indie bands, plumbers and undercover surveillance teams. But, according to a report published online in the journal Nature today (Feb. 21), physicists are getting ready to pack up a cloud of billions of antiprotons for the journey of a "few hundred meters" between the physics lab CERN's antimatter factory and the site of an experiment designed to figure out the shapes of bulky, radioactive atoms.

Antiprotons are rare but hugely important particles. Every matter particle has an antimatter twin, like the Jekyll to its Hyde, with exactly reversed physical properties. And antiprotons are the bizarro versions of protons, the positively charged particles at the center of atoms. When they collide with protons, they annihilate each other.

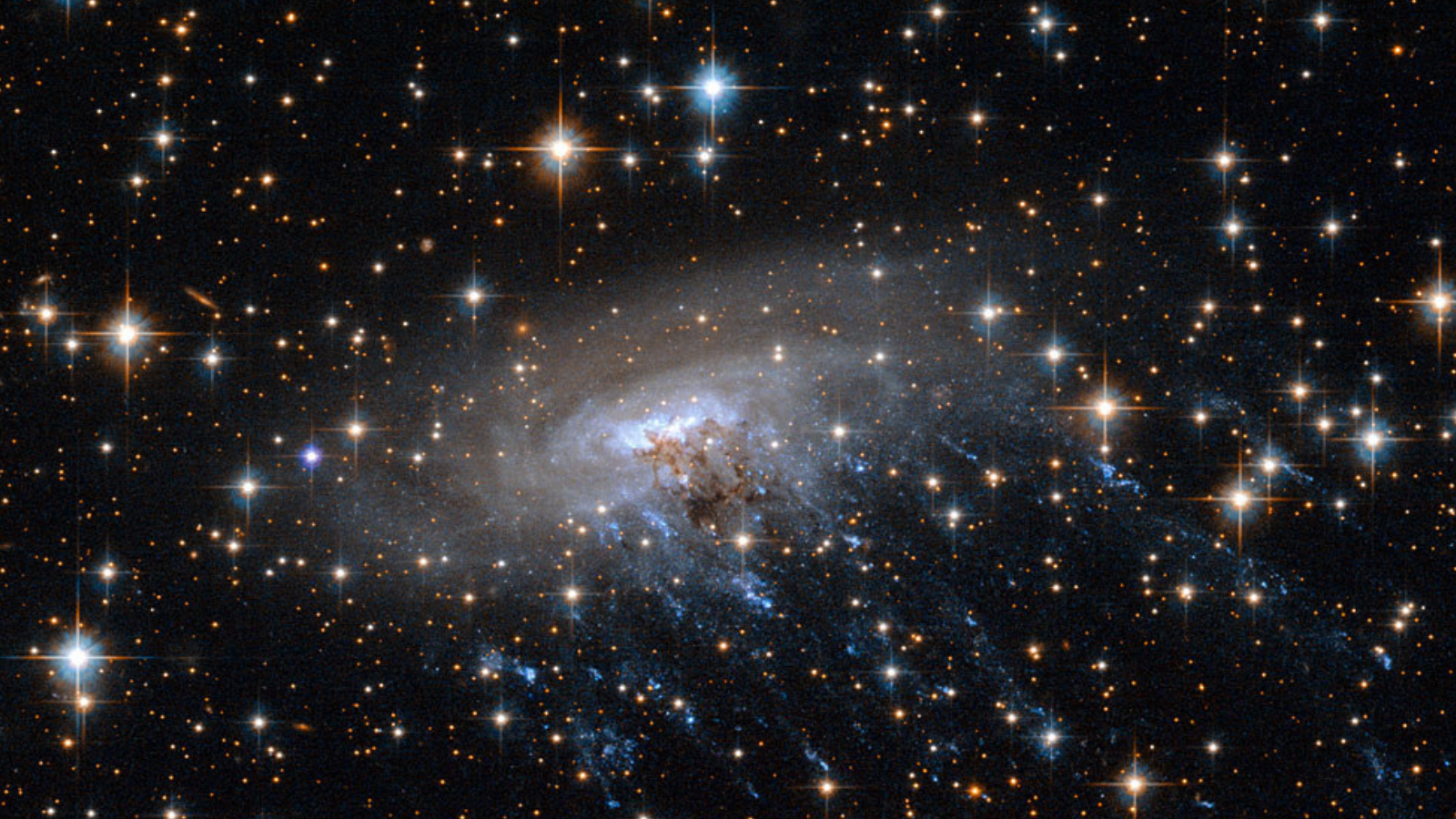

In nature, antimatter particles are pretty rare. Positrons (bizarro electrons) do occur in lightning bolts and occasionally show up in outer space, but they tend to annihilate one another long before they have a chance to accumulate. So physicists at the CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) physics laboratory near Geneva generate them, Nature reported, by "slamming a proton beam into a metal target, then dramatically slowing the emerging antiparticles so they can be used in experiments." [Photos - Behind the Scenes at the Largest US Atom Smasher]

And those collected antiprotons can be useful.

Researchers don't know, for example, exactly what the nuclei of big, radioactive atoms look like. A heavy isotope might contain dozens of protons and neutrons, and physicists have long known exactly how many of each there are. But they generally don't know how those particles are arranged. Are the protons clustered in the center, surrounded by a shell of neutrons? Do the neutrons orbit in a surrounding halo?

For a project called the antiProton Unstable Matter Annihilation (or PUMA), Nature reported, researchers plan to fire antiprotons at atomic nuclei and, by studying the annihilations, figure out how often those antiprotons collide with neutrons and how often they collide with protons. That will tell them a great deal about where each kind of particle lives in the nucleus. The process happens so fast that they expect to be able to study even the most short-lived nuclei — extremely heavy elements that exist only in laboratories for brief moments before decaying — Nature reported.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But to pull off the experiment, the researchers need to bring the antiprotons to the nuclei. To that end, they intend to magnetically trap large clouds of them — enough to last for weeks on end — in vacuum chambers, load those traps onto vans and drive them the short distance to the experiment site.

It's a short journey, but a first for the exotic particles.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.