These Are the Most Out-of-This-World Photos Ever Taken — Literally

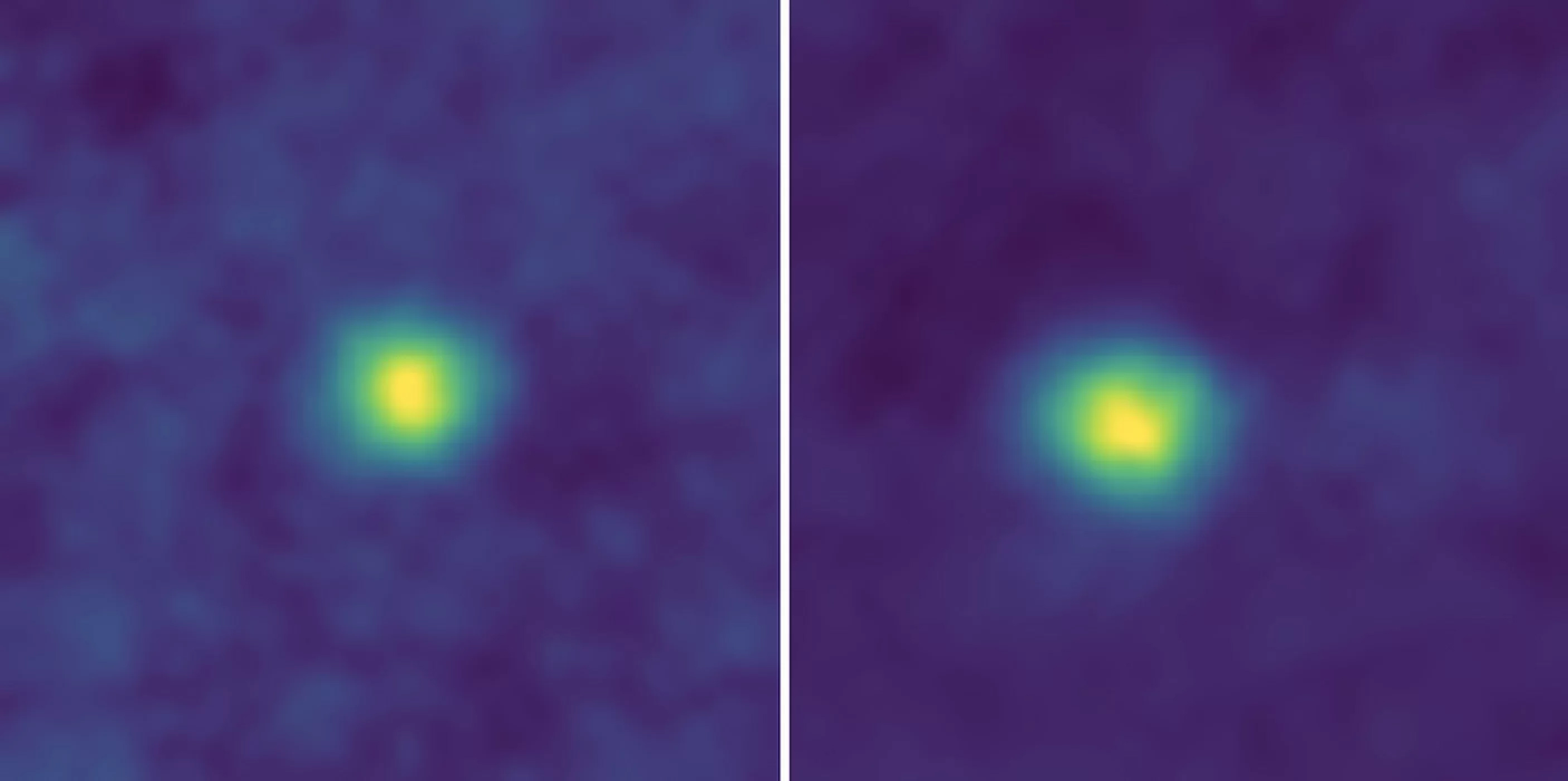

The photos don't look like much: blurry green splotches against pixelated blue. But they're arguably among the most amazing photographic images ever.

That's because they were taken from the farthest point from planet Earth of any images ever captured, snapped by a spacecraft just over 3.79 billion miles (6.12 billion kilometers) from its home planet. That spacecraft is New Horizons, a NASA starship that zipped past Pluto in 2015 and is scheduled to fly by an object in the icy Kuiper Belt at the outer reaches of the solar system in January 2019.

New Horizons snapped these two farthest-out shots, of Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) 2012 HZ84 and 2012 HE85, on Dec. 5, 2017. Just 2 hours before, the spacecraft had officially claimed the title of spaciest photographer by capturing a camera-calibration shot of a far-off star cluster known as the Wishing Well. It was a fleeting record, because 2 hours later, the two KBOs were imaged. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

Prior to New Horizons' star shot, the image taken farthest from Earth was one of the Blue Marble snapped by the Voyager 1 spacecraft on Feb. 14, 1990. That image, known as the "Pale Blue Dot," was taken from 3.75 billion miles (6 billion km) away.

New Horizons is headed toward a KBO dubbed 2014 MU69, one of more than 20 far-off chunks of rock and ice NASA hopes to observe during the spacecraft's mission. The Kuiper Belt is a disc-shaped expanse past the orbit of Neptune, about 2.7 billion to 9.3 billion miles (4.4 billion to 14.9 billion km) from the sun, that contains thousands of icy objects, comets and dwarf planets. (Pluto is one of these dwarf planets.) 2014 MU69 is nearly a billion miles beyond Pluto, which itself is 4.67 billion miles (7.5 billion km) beyond Earth. To get there, New Horizons is trucking: It travels more than 700,000 miles (1.1 million km) a day.

So how does New Horizons send back images, even blurry ones, through all that space? According to Johns Hopkins University, where the scientists in charge of the spacecraft's data communications are based, it's not easy. Data is stored in a solid-state recorder (the only moving parts in these flash memory devices are the electrons) on New Horizons and is then transmitted via radio waves. Needless to say, the signal strength is low — the antenna transmits at a power of 12 watts and receives signals at 1 million billionth of a watt — so the data transmission rate is painfully slow. The transmission rate for New Horizons is only about 2 kilobits per second. Even old dial-up internet moved data at a rate of 56 kilobits per second.

For the two record-breaking Kuiper Belt object images, it took about 4 hours to transmit each image and 6 hours for the data to travel to Earth, Alan Stern, the principal investigator on the New Horizons mission, told Live Science.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Earth, NASA's Deep Space Network antenna dishes catch the faint signals coming from New Horizons and reassemble the raw data into a usable form. For now, New Horizons won't be sending home any snapshots. According to NASA, the spacecraft is in hibernation mode until June 4, when mission controllers will bring it back online to start preparing it for its visit with MU69.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.