Pluto, Other Faraway Worlds May Have Buried Oceans

Our solar system may harbor many more potentially habitable worlds than scientists had thought.

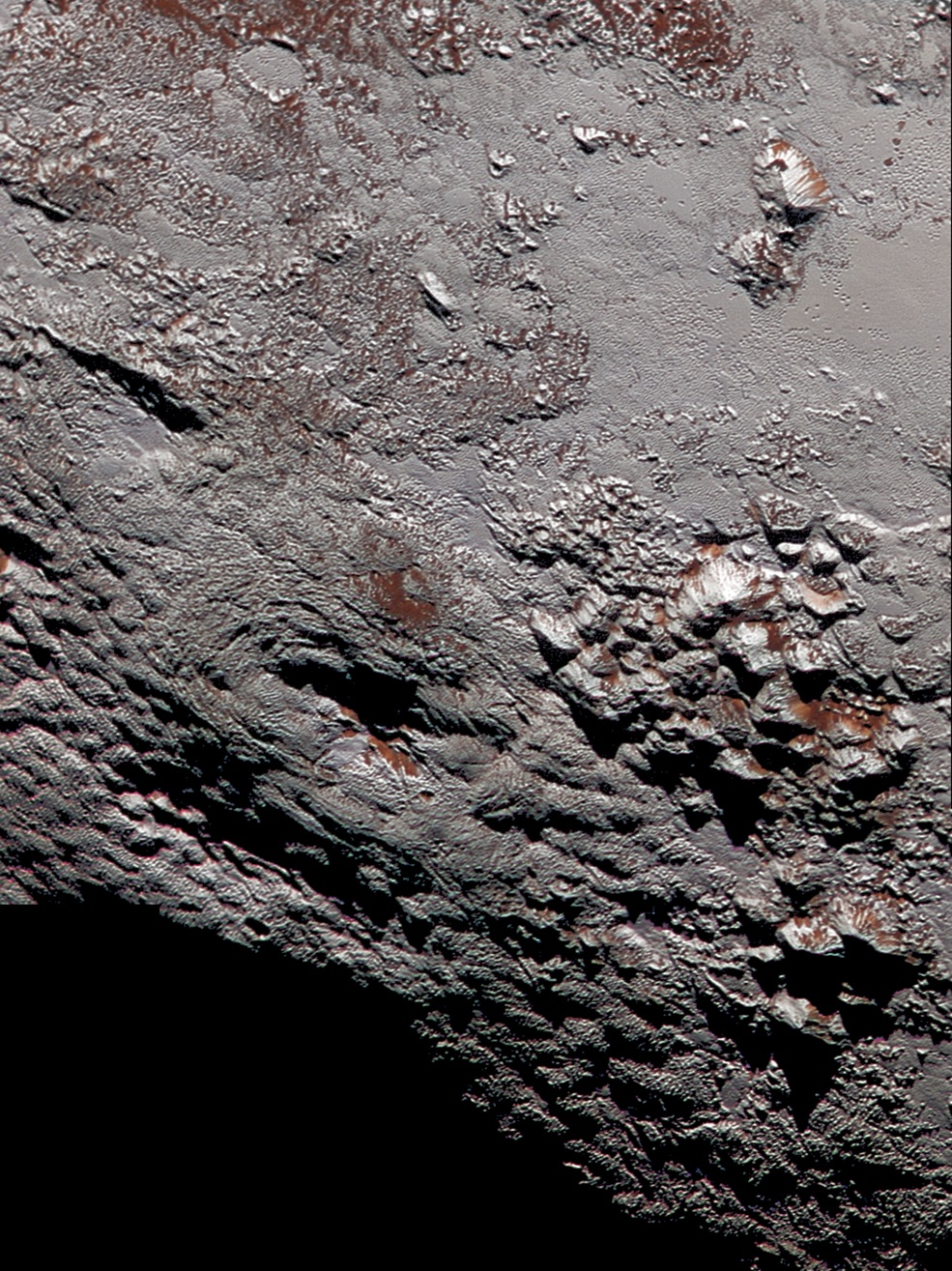

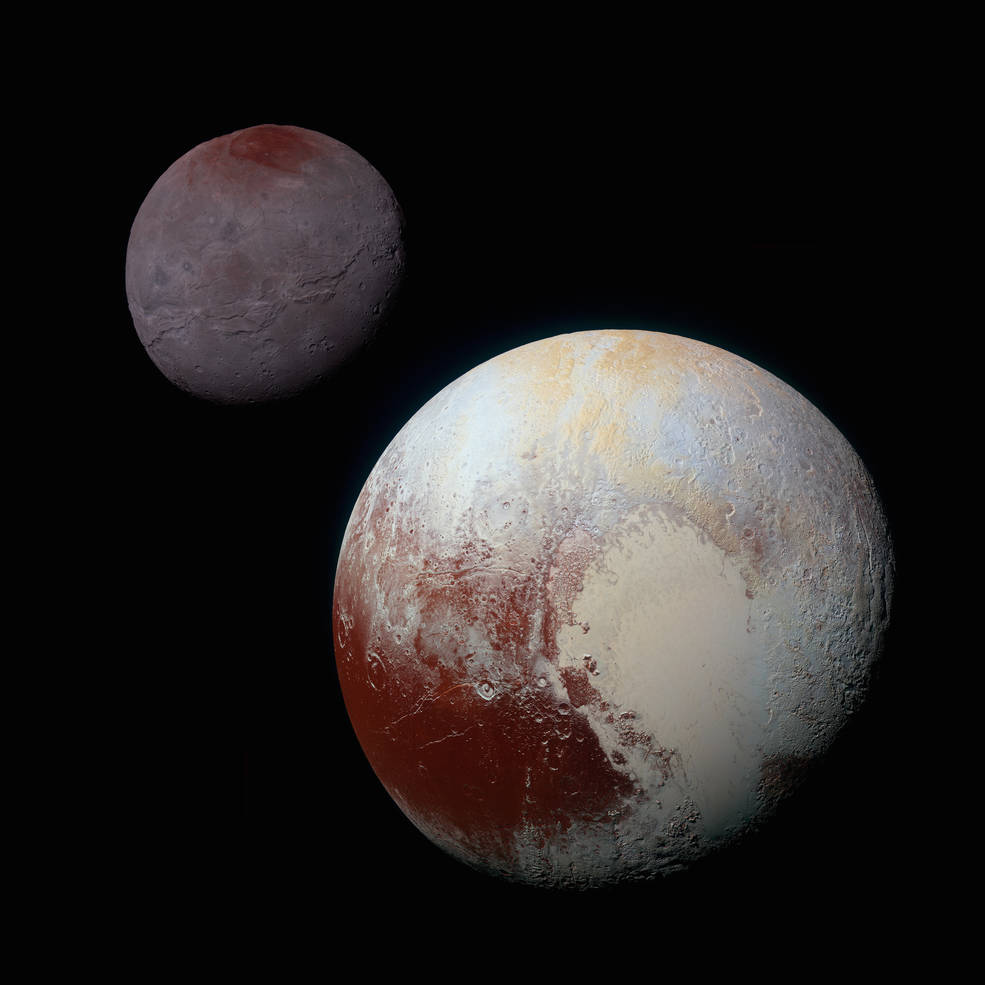

Subsurface oceans could still slosh beneath the icy crusts of frigid, faraway worlds such as the dwarf planets Pluto and Eris, kept liquid by the heat-generating tug of orbiting moons, according to a new study.

"These objects need to be considered as potential reservoirs of water and life," lead author Prabal Saxena, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement. "If our study is correct, we now may have more places in our solar system that possess some of the critical elements for extraterrestrial life." [6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System]

Underground oceans are known, or strongly suspected, to exist on a number of icy worlds, including the Saturn satellites Titan and Enceladus and the Jovian moons Europa, Callisto and Ganymede. These oceans are kept liquid to this day by "tidal heating": The powerful gravitational pull of these worlds' giant parent planets stretches and flexes their interiors, generating heat via friction.

The new study suggests something similar may be going on with Pluto, Eris and other trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs).

Many of the moons around TNOs are thought to have coalesced from material blasted into space when objects slammed into their parent bodies long ago. That's the perceived origin story for the one known satellite of Eris (called Dysnomia) and for Pluto's five moons (as well as for Earth's moon).

Such impact-generated moons generally begin their lives in relatively chaotic orbits, team members of the new study said. But over time, these moons migrate to more-stable orbits, and as this happens, the satellites and the TNOs tug on each other gravitationally, producing tidal heat.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Saxena and his colleagues modeled the extent to which this heating could warm up the interiors of TNOs — and the researchers got some intriguing results.

"We found that tidal heating can be a tipping point that may have preserved oceans of liquid water beneath the surface of large TNOs like Pluto and Eris to the present day," study co-author Wade Henning, of NASA Goddard and the University of Maryland, said in the same statement.

As the term "tipping point" implies, there's another factor in play here as well. It's been widely recognized that TNOs could harbor buried oceans thanks to the heat produced by the decay of the objects' radioactive elements. But just how long such oceans could persist has been unclear. This type of heating peters out eventually, as more and more radioactive material decays into stable elements. And the smaller the object, the faster it cools down.

Tidal heating may do more than just lengthen subsurface oceans' lives, researchers said.

"Crucially, our study also suggests that tidal heating could make deeply buried oceans more accessible to future observations by moving them closer to the surface," said study co-author Joe Renaud, of George Mason University in Virginia. "If you have a liquid-water layer, the additional heat from tidal heating would cause the next adjacent layer of ice to melt."

The new study was published online last week in the journal Icarus.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.